Fire Retardant FOIA Frolics Update:

FOIA Review at White House White House

Remember that I was curious about how the decision was made for the USG to not support a fire retardant bill that aimed to exempt fire retardant from CWA permitting. I had heard through a few grapevines that this was not the USDA position and they had been overruled. I was wondering how these disagreements are hashed out in the Biden Admin, and so I FOIAd CEQ and USDA Office of the Secretary.

I’m still waiting on a part of the FOIA from CEQ; their FOIA folks are incredibly helpful, so a big shout-out to them, as well as USDA FOIA folks! Unfortunately, there’s apparently a relatively new White House review process that requires all FOIAs with messages with emails “who.eop.gov” to be reviewed by the White House.. I guess this is the White House White House, not just CEQ, OSTP, USTR ,NSC, OMB nor any of those other White House “Executive Office of the President” agencies. You can find all the EOP agencies listed here. From now on, I’ll just call the White House White House as in “who.eop.gov” WH2.

It’s probably easier than calling them “Who”; could be confusing. As in “who’s on first” and so on. The good news is that one of our forest issues attracted the attention of someone in the WH2. Who? Why? What did they have to say? Time will tell, hopefully, when the review gets finished. Stay tuned. This review process seems to hold up transparency, which I think is a value of the Admin, so there’s that, or at least it was.

Biden plans to “bring transparency and truth back to the government to share the truth, even when it’s hard to hear,” she said.

I’m sympathetic, as saying you’re going to do things is easier than actually doing them. I have the same problem.

Why NSC Was on Email Chain

According to sources, NSC is usually involved in Wildland Fire issues. According to these sources, USDA tried to involve NSC to get the debate at the CEQ.EOP vs. NSC.EOP level (more level footing), as opposed to CEQ.EOP vs. Department level. Seems like a good strategy for USDA, even if it didn’t work this time. Perhaps the question was resolved at WH2. Thanks to FOIA, we should find out. And we should all thank TSW Contributor Andy Stahl for this opportunity to gain insight into the Department and EOP conflict resolution processes and the role of WH2.

Who Knew? Seed Orchards are Cool Again…

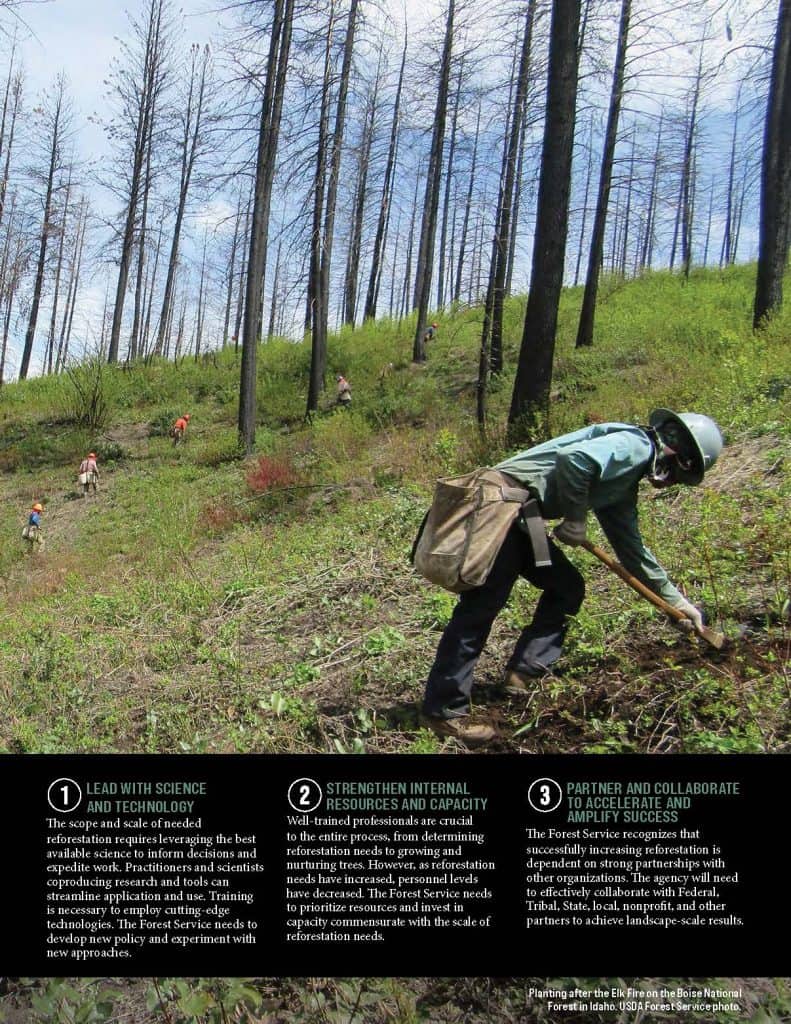

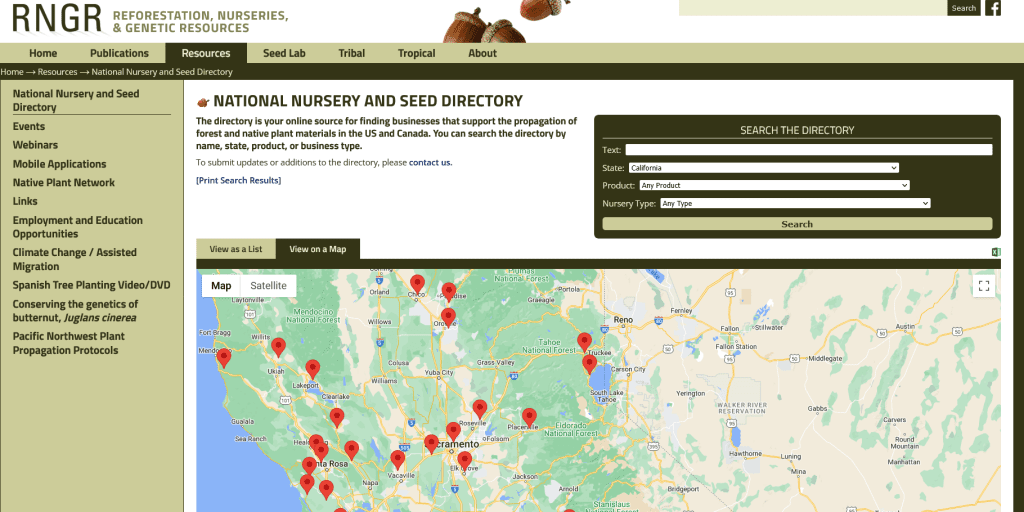

Just when you think everyone who knew about something is retired.. it becomes cool again.. reforestation, nurseries, and now at least one seed orchard! Since we are using them for good purposes now -as in climate adapation and carbon sequestration- reforestation is back to being white hat-ish at least.

Check out this video with Jad Daley of American Forests on a refurbished Gifford Pinchot NF seed orchard! As Jad says “let’s get to work on reforestation.” We finally have the bucks.

The Deep Fire in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest has been using pack mules to shuttle supplies to firefighters punching in handline “deep” in the forest. Crews have made tremendous progress. Other incidents in California in remote areas are still chunking away. The Smith River Complex in the Six Rivers National Forest is now 57,200+ acres and the Happy Camp Complex is pushing 16,000 acres on the Klamath National Forest.

Natural wanderers

Colorado’s last wolverine lived here between 2009 and 2012 after traveling 585 miles over a few months from the northwest corner of Wyoming to the mountains west of Breckenridge, crossing two interstates, several mountains ranges and Wyoming’s vast and arid Red Desert.

M56 was the first wolverine seen in the state since 1919, but it didn’t stay put. It eventually wandered out of the state and was shot and killed on a ranch in North Dakota.

Data collected by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service shows that wolverines are moving back into some of their previous territories all on their own.

That’s why Colorado officials should wait for wolverines to reintroduce themselves instead of forcibly moving wolverines into the state, said Jeff Copeland, executive director of the Wolverine Foundation and a wildlife biologist who studied the species for more than 30 years.

Wolverines have moved back into all of the lower 48 states they previously occupied except Nevada, California and Colorado, Copeland said.

“Reintroduction is kind of happening on its own,” Copeland said. “The fact that we can see that and watch it is very exciting to me.”

Wolverines have been spotted recently in places where they hadn’t been for a century. In June, a young male was spotted three times in and near Yosemite National Park in California. Utah wildlife officials have confirmed several sightings.

The species’ rambling nature is what gives Copeland hope that a human-initiated reintroduction won’t be necessary in Colorado.

“It’s a very messy process,” he said. “It’s a last resort. It’s not the first choice because you’re going through a capture process, trying to capture these animals, transport them thousands of miles and then drop them off in completely new habitats and expecting them to live.”

Because wolverines do not live near each other, taking one or two will impact the ecosystem of that area, Copeland said.

But other advocates for the species said there is risk in waiting and hoping that wolverines reestablish themselves here. Even if a breeding pair make its way down south, more will have to follow to make sure there is enough genetic diversity, said Michael Robinson, senior conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity.

“Colorado should do it on the principle that wolverines belong in Colorado,” Robinson said. “They’re part of the natural ecosystem and Colorado’s ecosystem can make a big difference.”

I also think it’s interesting how ideas about ecosystems and climate change are blended in this article.

“The governor continues to join so many Coloradans who share his enthusiasm for reintroducing the native wolverine, last spotted in 2009 in our state, to better restore ecological balance in wild Colorado areas,” Gov. Jared Polis’ spokesman, Conor Cahill,

Colorado’s high snowy mountains are the species’ largest unoccupied territory and will only become more important as a warming climate shrink the snowpack the wolverines need for dens.

“There is a real role for Colorado to play in conservation here,” Odell said. “Wolverines really need Colorado.”

The most significant stressor on wolverines in the coming years will be climate change, according to an analysis by the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Wolverines create high-altitude dens in the snowy mountains in the winter and raise their kits there to keep them warm and protect them from predators. Wolverine mothers need deep snow that lasts long into the spring months.

That type of snow will become rare in the American West as the climate warms. Wolverines will lose an estimated 30% of their habitat in the lower 48 states in the next 30 years and 60% of their habitat here in the next 70, according to the National Wildlife Federation.

The seedling program allows farmers, ranchers, other landowners and land managers to obtain trees at a nominal cost to help achieve conservation goals, including:

The seedling program allows farmers, ranchers, other landowners and land managers to obtain trees at a nominal cost to help achieve conservation goals, including: