Maybe this is one possible (small) advantage of state ownership (vs federal) of public lands in one state. In Montana you (and I mean you, or any environmental group) can bid on a 25-year “conservation license” in lieu of a timber sale. In what I believe may be a first in Montana, there was such a high bidder. It’s maybe a fairly unique situation, where adjacent landowners could afford to pony up the $100ks for what appears to amount to a limited-term scenic easement. This makes some sense for the state if the goal for land management is dollar returns. Of course the actual timber bidder is protesting it. Both sides have raised questions about what the statutory language for state lands means when it says: “secure the largest measure of legitimate and reasonable advantage to the state.” Should it include the “benefits” of roads that would be built (but not the environmental costs); should it include the long-term economic value of being able to resell the same timber in 25 years? (Is this a good idea for public lands?)

Trust Managaement

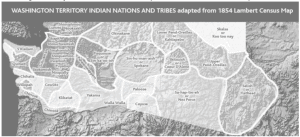

Supreme Court may reinterpret tribal treaty rights on national forests

Here’s a pending Supreme Court case, Herrera v. Wyoming, that hasn’t shown up in the Forest Service litigation summaries. The federal government is defending the right of a Native American to hunt on the Bighorn National Forest without complying with state hunting laws. If they lose, tribal treaty rights, as currently understood, could be severely diminished. The hearing is scheduled for January 8.

When the native tribes ceded their lands to the federal government, the language in the treaties typically preserved their rights to various uses and activities on indigenous lands that were not included within the new reservation, for which the treaties used the terms “open and unclaimed” or “unoccupied” lands. Much of that land is now part of national forests. Here is how the Forest Service interprets the language referring to those lands:

The term applied to public domain lands held by the United States that had not been fenced or claimed through a land settlement act. Today, “open and unclaimed lands” applies to lands remaining in the public domain (for the purposes of hunting, gathering foods, and grazing livestock or trapping). The courts have ruled that National Forest System lands reserved from the public domain are open, unclaimed, or unoccupied land, and as such the term applies to

reserved treaty rights on National Forest System land.

In the case currently pending before the Supreme Court the State of Wyoming has argued that this is not true (they also argue that the lands became “occupied” when Wyoming became a state):

The parties further dispute whether the Bighorn National Forest should be considered “unoccupied lands” for treaty purposes. Herrera and the federal government emphasize that the proclamation of a national forest meant the land could no longer be settled, which they argue was the historical standard for occupation. Yet Wyoming argues that physical presence should not be the test, especially given the West’s expansiveness. According to Wyoming, the federal government’s proprietary power over its own lands, including its decisions to exclude hunters, demonstrates that the land was effectively occupied when it became a national forest.

Courts have held that the federal government has a substantive duty to protect ‘to the fullest extent possible’ the tribal treaty rights, and the resources on which those rights depend. If Wyoming were to win their argument, treaty rights to accustomed tribal uses of national forests would no longer exist. Because the federal government is defending the tribal interests in this case, one might think that the Forest Service would continue to protect these rights even without the treaty obligation. However, in the past they have disagreed with tribes on issues such as campground fees and desired salmon populations.

Klamath Westside salvage project

I thought this article provided a succinct overview of the state of salvage logging in California. I was curious about what kind of a logging project the Center for Biological Diversity and local environmental groups were supporting.

Table 11 in the ROD shows that the tribal alternative they supported would harvest about 2000 acres. The selected alternative would log three times that. Why did the Forest Service pick the latter over the former?

“As shown in Table 12 (sic), there is considerable overlap between the Karuk Alternative and the Selected Alternative;”

Did the FS miss the obvious point here? That the magnitude of the project is the problem because it would affect water quality and salmon runs? (Or is this what “pound sand” means?)

It was also interesting to read the earlier letter from the Karuk Tribe chairman that describes the tribal interest in prescribed fires. I wonder if the Forest Service has considered managing the historic tribal lands for “production of acorns, wild game, medicinal plants and basketry materials,” among its multiple uses.

What Should Congress Do? II Trusts

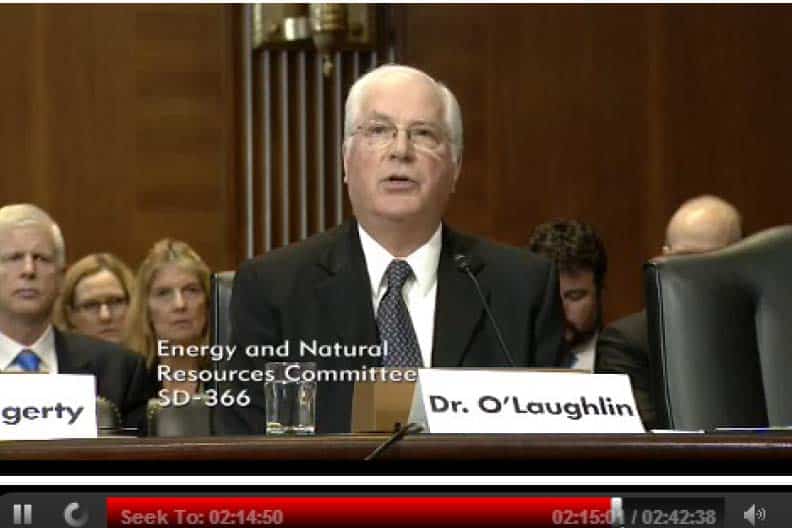

This post involves information from Mac McConnell, Jay O’Laughlin and about the Valles Caldera experiment.

Solving these many and diverse local problems require local solutions based on local know-how. The current topdown,

one-size-fits-all land management by the feds has proven itself incapable of problem-solving at the forest

level. Removal of selected lands from federal oversight and transferal to local autonomous authority, similar to

state trust lands, would seem to be the most direct and efficient way – perhaps the only way – to secure reliable,

adequate funding and cut through the tangle of shifting, restrictive, and often conflicting laws, regulations,

executive orders, litigation, and judicial mandates that make federal management a hopeless cause.

Here is an in-depth look at this option, from Mac.

Jay O’Laughlin has also published some papers on trusts as a solution to some federal lands problems. Here is avery thorough one with charts and tables, and here is his testimony from a hearing in March. rough and one and here is his testimony at a Congressional hearing in March.

I’m interested in 1) what you think of the trust idea in general, and 2) whether you think a pilot might be feasible as a test case (or adaptive management). Perhaps O&C lands? Or somewhere else? Why would that area be good for a pilot?

3) What have we learned about trusts through the Valles Caldera trust experiment?

I was just reading about how:

from the Sierra Club

The Sierra Club, Caldera Action, National Parks Conservation Association, New Mexico Wildlife Federation, Coalition of NPS Retirees, Audubon and others have been pushing to replace the current experimental trust management with the National Park Service since around 2007.

Many people feel Valles Caldera is a National Park-quality place and it could be well protected and a tremendous economic asset to Northern New Mexico when the National Park Service assumes management of the land as a preserve.

Maybe any place placed into trust would be a “non-National Park quality” place? But I wonder if to the NPCA,to the retirees, and to the Sierra Club everyplace is “National Park quality” either now, or once current users are removed.

The grazing language now reads that the National Park Service “shall” permit livestock grazing but the NPS will have full discretion about where cows can be, when, and how many.

So to a pilot, we would have to find a place that most folks would say is not “National Park Quality”. Perhaps lots of timbered country, no pretty canyons, lots of existing roads. In a state with existing land trusts. Perhaps Northern Washington or Idaho?

Rocky Barker: Good reasons why federal forests don’t pay like the state’s

Here’s the link and here’s an excerpt.

In the days when the Forest Service did try to emphasize making money from logging, it lost support across the West because it was clear-cutting.

No matter how many times the timber industry tried to put a good face on that accepted forest practice, the public just didn’t like looking at clear-cuts. Much of the federal forest timber program was shut down by litigation and lack of money for roads, along with water-quality problems and endangered species issues.

Otter noted that timber harvests on federal lands in Idaho are the lowest they have been since 1952. They are actually beginning to rise, however, in part due to the collaborative efforts of timber executives, environmentalists and others to identify timber that can be sold.

Private forests and state forests are, by definition, high-value forests. If they weren’t, the owners would have disposed of or traded them in years ago.

But the Forest Service doesn’t manage forests for a profit. You don’t hear the conservation groups that are supporting new mills and increased timber harvests and jobs complaining about timber sales that lose money.

That’s because they know the restoration value for wildlife and fish habitat that comes with timber sales are a part of the cost of managing forests for multiple uses.

Private and state forests are managed for maximum timber harvest. The recreation, habitat and other values that come from those lands are secondary. That’s why you can go to some state forests in Idaho and clearly see the difference between them and the federal forests next door.

It’s the state forests that are still being clear-cut.

Sharon’s take: It’s still not clear to me (so to speak) why clearcutting still comes up as an issue when the FS hasn’t done it in a while. Anyone who can help with this, especially from Idaho, please comment.

Hearing on Forest Service Management and Trusts by House Resources Committee

Here’s a link to the report. Thanks to Derek!

Also here is a piece from E&E news daily. Below is an excerpt.

Legislative proposals from last Congress

In concept, yesterday’s proposals are similar to legislation introduced last Congress by committee Chairman Doc Hastings (R-Wash.) to require the Forest Service to establish “trusts” under which logging and other projects must meet historic revenue targets. Such projects would be exempt from major environmental laws, including the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act, and would set firm deadlines for approvals.

That proposal was vigorously opposed by environmentalists, who argued that it would subject forests to vast clearcutting and create the perverse incentive to cut more logs even if the price of timber was low. Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), chairman of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, last Congress said the proposal would reignite the timber wars of the late 20th century.

A separate proposal by Oregon lawmakers last Congress would have transferred roughly half of the 2.4-million-acre O&C lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management to a state-appointed timber trust, under which NEPA and some provisions of ESA would not apply.

But Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.), who authored the bill, said their proposal was different because BLM’s O&C lands are statutorily distinct from Forest Service lands. While Forest Service lands fall under laws mandating clean water, multiple use and species protections, among others, O&C lands were designated primarily for timber production.

Trust proposals on Forest Service lands may fly in the Republican-led House but would never pass Congress, he said.

“National forestlands are managed under a whole different set of laws; there is no relationship,” he said. “They may be trying to mimic what we proposed, but there’s no legal authority.”

Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-Ariz.), the ranking member on the subcommittee, asked how such trust lands would be chosen, how conservation and recreation interests would be represented, and which environmental laws would still apply.

“State trust lands are set up for a singular purpose, to produce revenue,” he said. “Federal forests on the other hand have a broader mandate and a wider set of management goals, with multi-use options.”

He urged Republicans to avoid “radical ideas” that won’t move in the Senate and to focus on policies that would make forests healthier and safer for constituents.

“Delegating the management of American resources to the states is still in and of itself a radical idea,” he said. “To imagine that the long-standing struggle over the use of our national forests will somehow disappear if they are turned over to the state is just pure fantasy.”

Bishop said yesterday’s hearing was the first of several this Congress to focus on “shifting this paradigm” of federal forest management.

It comes several months after the expiration of the Secure Rural Schools program, which for more than a decade subsidized Western counties where federal timber revenues plummeted in the 1990s. Lawmakers this Congress will be examining ways to extend the law, reform it or return to a commodity-based system favored by many Republicans.

So the problem with having the different houses of Congress controlled by different parties is that they can just agree among themselves, and blame the other house (Party) for not getting together.

So how can we help? We could set up a separate forum of people of all persuasions to discuss A Sensibe Solution. Congress could establish a bipartisan group. Or we could let D governors work it out since it appears to me that some environmental groups don’t think there is a problem, and if D governors are responsible for a state and feel that there is a problem, they may be in the best political space to broker a solution. Maybe that’s why some folks like nationalizing issues; it gets to our currently ineffective Congress and the status quo remains indefinitely.

What do you think? Do we need an extra-Congressional bipartisan policy seeking group? Is there any history of success of such a group we could point to?

Trusts, More Generally- A Guest Post from Steve Wilent

Folks, Here’s an excerpt from my Editor’s Notebook column from August 2012, in which the two main types of trusts are defined, thanks to the folks at the conference mentioned: public trusts and real trusts.

Steve Wilent, Editor, The Forestry Source.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

The conference I mentioned, “Trust Management: A Viable Option for Public Forest Lands?”—sponsored by the Western Forestry and Conservation Association and the American Forest Resource Council—was held in June in Tigard, Oregon. The event featured notable speakers such as Jay O’Laughlin, director of the Policy Analysis Group at the University of Idaho’s College of Natural Resources; Ann Forest Burns, AFRC vice-president; and US Rep. Kurt Schrader, of Oregon. Elaine Spencer, an attorney with Graham & Dunn PC, a Seattle-based law firm, explained a key concept: The difference between a “public trust” and a “real trust.”

Washington’s Department of Ecology, for example, bases its management of shorelines on the public trust doctrine, a legal principle derived from English Common Law: “The essence of the doctrine is that the waters of the state are a public resource owned by and available to all citizens equally for the purposes of navigation, conducting commerce, fishing, recreation, and similar uses and that this trust is not invalidated by private ownership of the underlying land. The doctrine limits public and private use of tidelands and other shorelands to protect the public’s right to use the waters of the state.”

Protection of the trust is carried out through laws such as the state’s Shoreline Management Act.

In contrast, in a real trust, or real property trust, land or some other real asset is held in trust for specific beneficiaries. Washington has about 2.2 million acres of trust land—public land that is managed for timber, agriculture, grazing, and other uses. The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (http://www.lincolninst.edu) describes it this way: “Unlike public lands, state trust lands are publicly owned lands that are held in trust by the state for specifically designated beneficiaries. As trustees, the state Legislature has a fiduciary duty to manage the lands for the benefit of the beneficiaries of the trust grant. These lands are managed for a diverse range of uses to meet that responsibility—generating revenue for the designated beneficiaries, today and for future generations.”

In Washington, the state trust land beneficiaries are schools, state universities, prisons, and other institutions.

Forest Trust Beneficiaries – Forestry Source August 2012-1 a link to Steve’s August 2012 editorial “Forest Trust Beneficiaries – Forestry Source August 2012.

Wyden to tackle forestry issues early in 113th Congress

This is from E&E news and posted here.

Below is an excerpt:

Wyden to tackle forestry issues early in 113th Congress

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) said forestry issues will be among his top priorities when he becomes chairman of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee next Congress, including bills to accelerate restoration logging in Oregon and other parts of the West.

Wyden, who once described the Beaver State as the “Saudi Arabia of biomass,” is seen as more supportive of “place-based” forestry bills than current committee Chairman Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.), who is retiring at the end of this month after 30 years in the Senate.

Wyden said he will push hard for bills such as his S. 220, which would promote active management on 8.3 million acres of forests east of the Cascades, and that he would consider similar bills such as a proposal by Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.) to accelerate forest restoration and designate wilderness in western Montana.

Wyden said he discussed forestry issues with Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), the committee’s ranking member, during a recent trip to Alaska, which, like Oregon, saw timber harvests plummet over the past decades as a result of protections for old-growth trees and the species they support.

“I think there are a lot of opportunities to find common ground on forestry,” Wyden said in a brief interview last week. “I think there is a chance to possibly build a coalition between these hard-hit rural communities that are worried about becoming ghost towns and get them off what I really call their own version of a fiscal cliff.”

As chairman, Wyden will have a full slate of forestry issues to tackle, including the expiration of the Secure Rural Schools program, which provides financial aid for timber-dependent counties, a continuing bark-beetle epidemic and increasingly severe wildfires as a result of dry, overstocked forests.

Trust-y Federal Land Management- O&C Version

When I started reading the news stories about this, I felt like I’d come into the middle of a novel.

First, I’d like to start with some thinking by Bob Malmsheimer of SUNY ESF, who said something along the lines of “we can never have a meaningful discussion about “trust management” until we clarify exactly what we mean. The term is used in so many different ways.” I think he raises an excellent point, so here on this blog we will try to be clear about these concepts and language.

This piece will be about O&C efforts, and, as we will see “trusts” are only one of the ideas involved once we look more closely.

So with the help of Steve Wilent, I managed to find enough pieces of the O&C puzzle so that perhaps we can begin to understand what’s going on. Since it seems fairly complicated, we will probably have a number of posts. Clearly, looking through the news “clippings,” there has been a great deal going on so I’m hoping readers from Oregon will help us catch up.

The most recent piece of news was Enviro Groups Letter to Wyden Dec. 2012-2 letter of some environmental groups to Senator Wyden.

That letter referred to something called ““Principles for an O&C Solution: A Roadmap for Federal Legislation to Navigate both the House and Senate”.

So I went looking for them, and the only place I could locate them was on Andy Kerr’s website here. Obviously I can’t vouch for their accuracy, but thankfully he posted the Governor’s and the Senator’s principles in one place. Now for those of you who aren’t following this, Andy Kerr is the same person who “bolted” from the Governor’s county payments panel based on clearcutting as in this news story. There appears to be another proposal for the O&C lands from environmental groups based on this piece by Jim Petersen in Evergreen, but I couldn’t find that either. So here is what Andy Kerr posted:

The Governor’s O&C Principles and the Senator’s O&C Principles

Though the attention for the present is on Governor John Kitzhaber’s attempt to resolve the O&C lands management crisis by convening a group of stakeholders from the O&C counties, timber industry and conservation community (as many of you know, I am of the view that the Governor’s choices to represent the conservation community are not representative of the conservation community as a whole), given that controversy involves federal public forestlands, it will be the forthcoming effort led by Senator Ron Wyden that will be controlling on the issue.

Here are the Governor’s O&C Principles:

• Stable County Funding – Recognize O&C Act’s unique community stability mandate and provide adequate and stable county revenues sufficient to meet needs for basic public services.

• Stable Timber Supply – Provide adequate and stable timber supply that will provide for employment opportunities, forest products and renewable energy.

• Protect Unique Places – Permanently protect ecologically unique places.

• Durable & Adaptive Conservation Standards – Maintain Northwest Forest Plan forest management standards – Late Successional/Old Growth Reserves & Aquatic Conservation Strategy – in an adaptive manner where and when required to comply with environmental laws.

• Conservation Opportunities – Promote conservation advances on private “checkerboard” lands through voluntary, non-regulatory incentives – financial, technical, regulatory relief, etc.

• Federal Budget Neutral – Recognize that O&C solution will need to be budget neutral or positive at the Federal level.

·• Achieve Certainty – Develop a policy framework that will provide for certainty in achieving all of these principles.Here are the Senator’s O&C Principles:

Principles for an O&C Solution

A Roadmap for Federal Legislation to Navigate Both the House and the Senate

1. STABLE FUNDING FOR COUNTIES: Oregon rural counties must be assured a stable level of funding from the Federal government due to the large extend of public lands they contain. Those funds can come through public lands receipts of through another mechanism created by this, or other, legislation. In the current fiscal climate that funding will not be able to replace historical levels of receipts, nor will timber receipts be able to fully provide for all funding needs. Recognizing that Oregon’s rural communities are suffering with high unemployment and unique economic challenges, they also need to do their part in reducing disparities in tax rates and developing a reasonable level of revenue from local activities. However, the Federal government must do its share to compensate counties for the impact of federal lands and the policies governing those lands.

2. SUSTAINABILITY: Timber harvest must be economically and environmentally sustainable. Timber harvests must produce more commercial product from O&C lands than is currently being produced and harvest should be guided by a scientifically-based, sustainable management regime that will meet or exceed the stated goals of the relevant federal and state environmental laws. Opportunities for active and adaptive management could included a variety of examples, such as the ecological forestry principles promoted by Norm Johnson and Jerry Franklin, as well as the pilot projects being currently promoted by various collaborative groups in Southern Oregon.

3. CONSERVATION: In addition to increasing timber harvesting, this legislation must result in wilderness and other permanently conserved lands proportional to the lands designated for harvest. These should include protection of both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, including large blocks of Bureau of Land Management lands and old-growth forests.

4. MANAGING LANDS MORE EFFICIENTLY: The legislation should seek opportunities to consolidate O&C and non-O&C lands. This will include addressing the checkerboard pattern of the O&C ownership and exchanging lands according to their best use whenever possible. It must develop an approach to rationalize land management between the O&C lands and adjoining private and public lands, both for timber and conservation values. The legislation should consider setting in motion a process to seek greater consolidation and management efficiencies on federal lands going forward.

Any consolidation or exchange should take into account concerns of neighboring private landowners, including access, rights of way and wildfire. The discussion should also address opportunities to finally honor unrealized treaty obligations to the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians, and the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians, understanding that some lands considered for their reservations may not be O&C lands. Both tribes have treaties pre-dating the O&C Lands Act.

5. LEGAL REQUIREMENT FOR TIMBER MANAGEMENT: Management of these lands must comply with all applicable Federal laws. Development of the plan should include open discussions on how to better implement the National Environmental Policy Act. There should be particular focus on streamlining the objection processes (for example, as included in the Healthy Forests Restoration Act and Senator Wyden’s Eastside Forestry legislation), and categorical exclusions for timber projects and other defined situations.

6. CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES FOR LAND MANAGEMENT: Due consideration should be given to proposals for non-Federal entities managing lands designated for conservation or active management as long as their is broad support for the proposal among stakeholders. Negotiations must take into account the failures of other private management efforts and the general opposition to private management of federal lands in Congress.

7. SAFEGUARDING OLD GROWTH: Oregon’s old growth must be protected. Old growth should generally be defined as 120 years of age or older, with exceptions made for significant ecological reasons.

O&C Trust Draft the draft bill that perhaps the environmental groups were responding to…

This is the beginning of the dialogue, and I am trying to catch up. Others can add links to documents and their opinions..