Folks have sent me some articles about the Chief’s testimony last week on the budget. From what I’ve heard and the stories, Congressfolk don’t seem as interested as retirees (including Dave Mertz and I, as well as others) in the Keystone Agreements and exactly where the funding is going, producing annual reports with details and so on. We were told “you can FOIA it” and my usual sources of info have dried up.

I’ve pointed out that we have nice reports on GAOA funding and where it goes, and Forest Legacy Funding via LWCF (Land and Water Conservation Fund). So my hypothesis is that it’s important to be transparent so that Congress continues to provide funding. The Keystone Agreements are conceivably one and done, so maybe that is why there’s so little perceived need for reporting or accountability? Or maybe the funding is going towards more capacity-building or planning so it’s harder to describe any outcomes or outputs. Or maybe it’s all there somewhere on a website and I missed it.

Anyway, back to Forest Legacy. Their site shows the specifics of each project, how many acres, partners and why each particular chunk of land is important.

The press release refers to “conserving” 168K acres of forestland. I still wonder whether conservation is defined differently between USDA and Interior. If not, then “conservation leases” could include (sustainable) timber harvest.

USDA’s Forest Service is providing more than $154 million through its Forest Legacy Program for 26 projects to conserve working forests that support rural economies in 17 states. This conservation work is made possible by more than $84 million from the Land and Water Conservation Fund and nearly $70 million from President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act – the largest climate investment in history and part of the Investing in America agenda.

Through the Forest Legacy Program, States work with local communities to identify private forestlands and develop proposals to conserve these lands as forests for their values as places for recreation, as wildlife habitat, and as sustainable sources of wood and other forest products. The Forest Service then selects the top proposals for funding through an entirely voluntary competitive process and provides grant funding to States. Some of this land will stay in private ownership and will be permanently protected and conserved as forests, while States will purchase other parcels to be managed as public land.

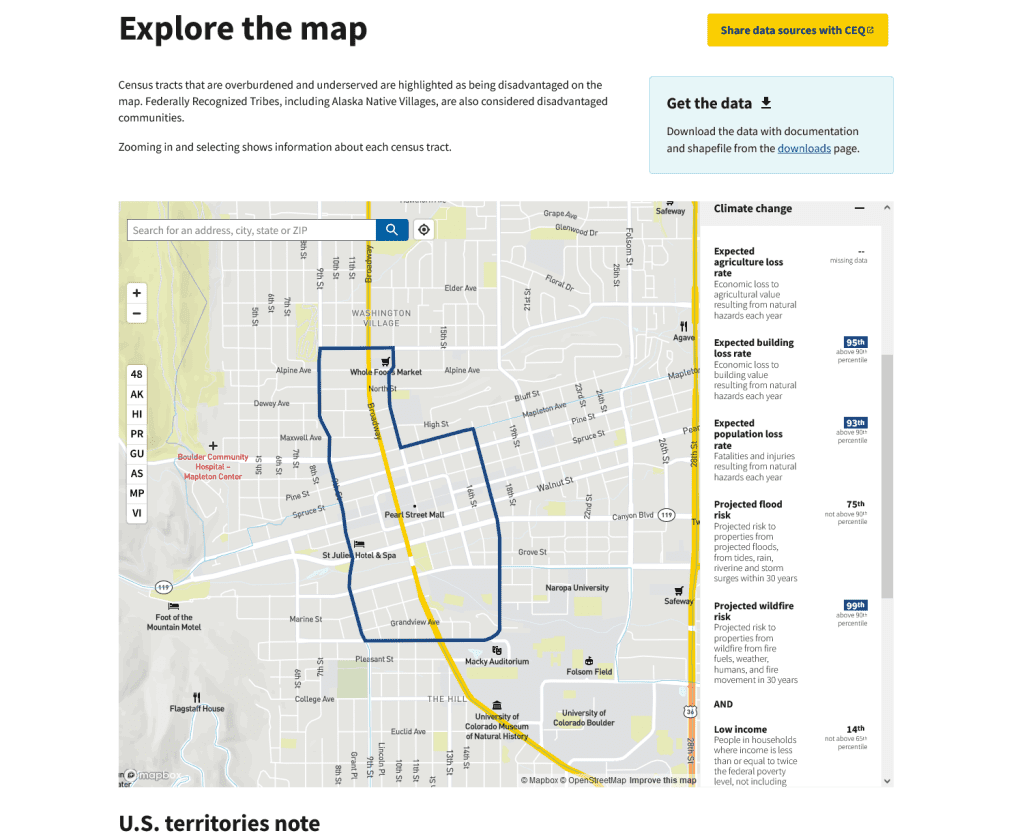

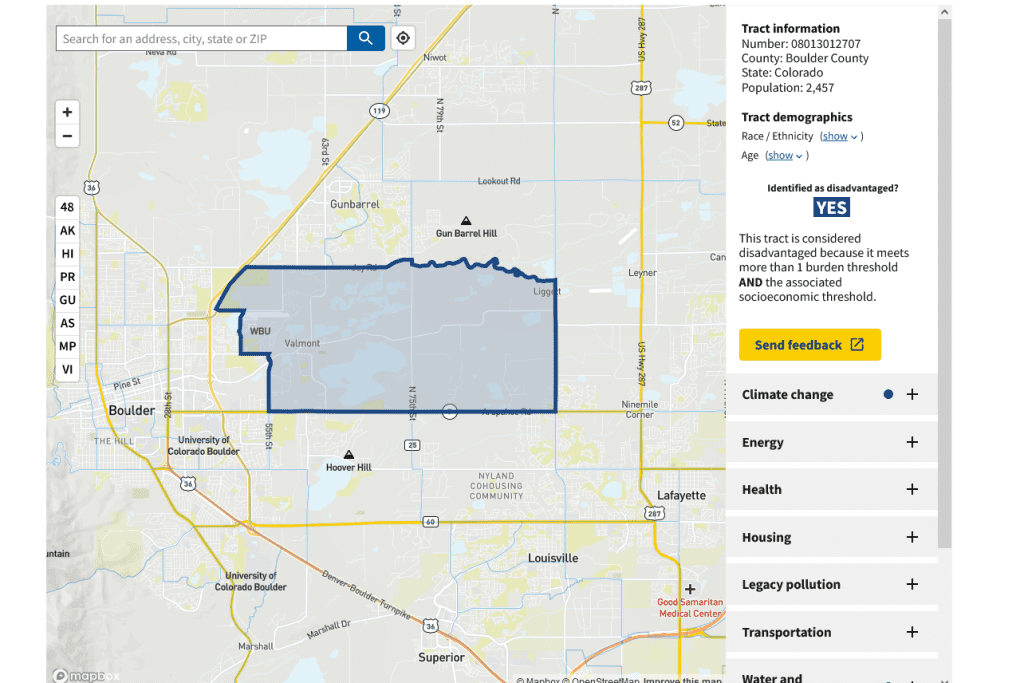

The Forest Legacy Program is also part of President Biden’s Justice40 Initiative, which sets the goal that 40% of the overall benefits of certain federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution. Communities around the nation depend on forests, and the effort to conserve private forestlands will benefit Tribal Nations and other disadvantaged communities. Nearly 50% of these investments will go to conserving forests near disadvantaged communities identified by the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool.

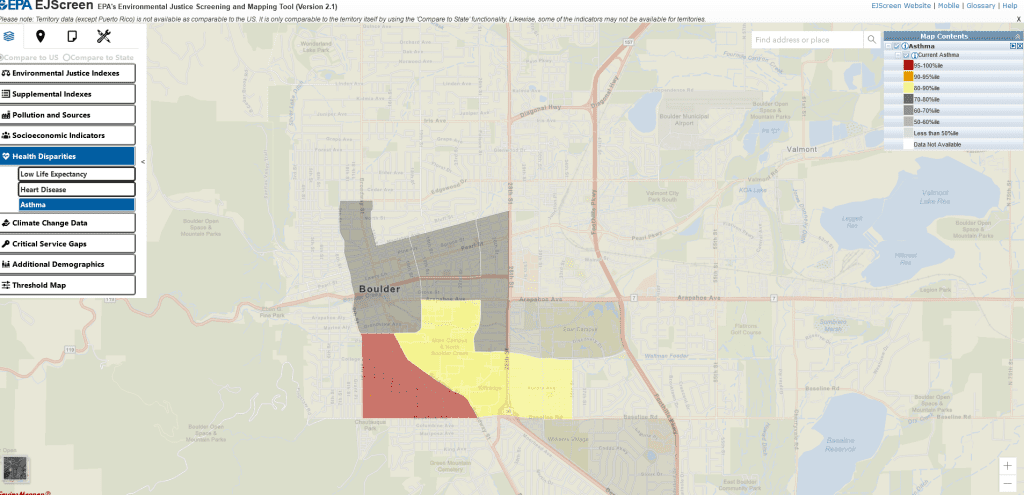

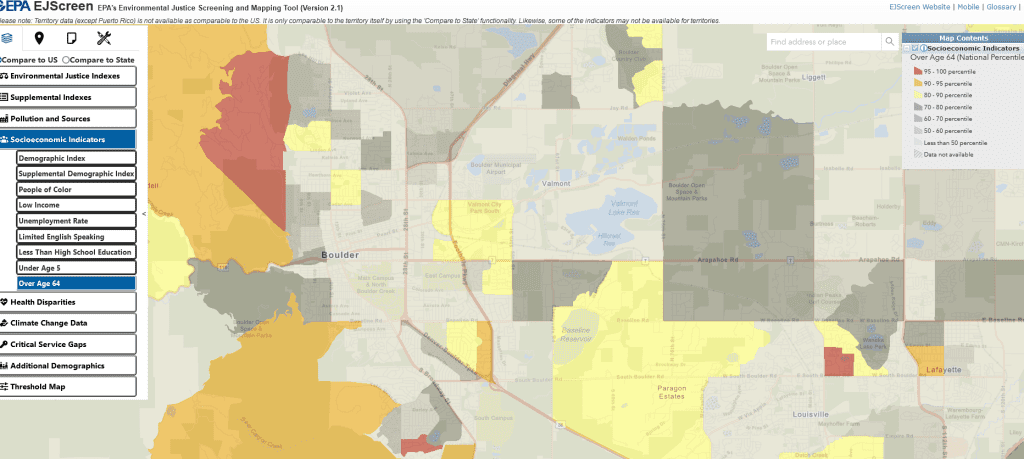

But the Screening Tool doesn’t just address disadvantaged folk and pollution- so the policy and the tool don’t seem to match.

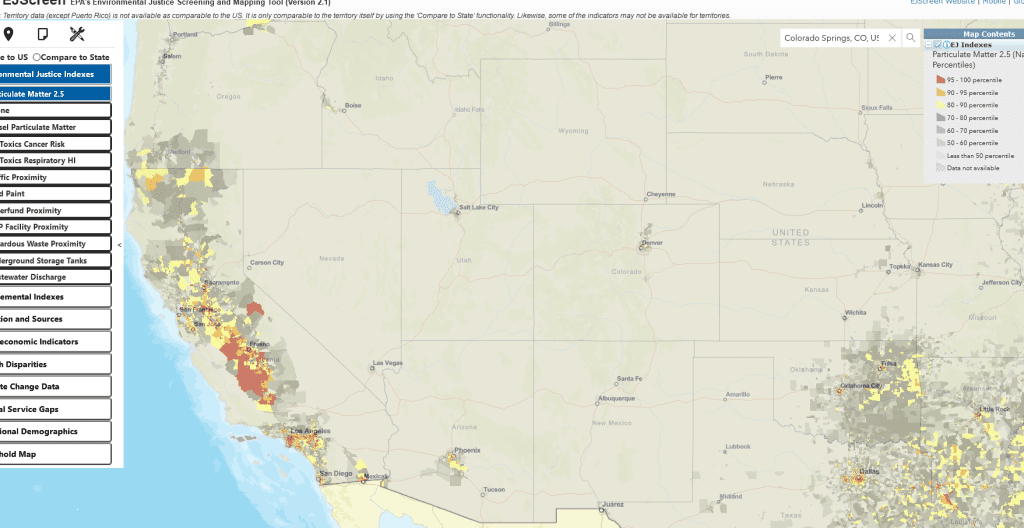

You’ll remember that I posted before here and here about the Screening Tool and its questionable protocols and data sources.

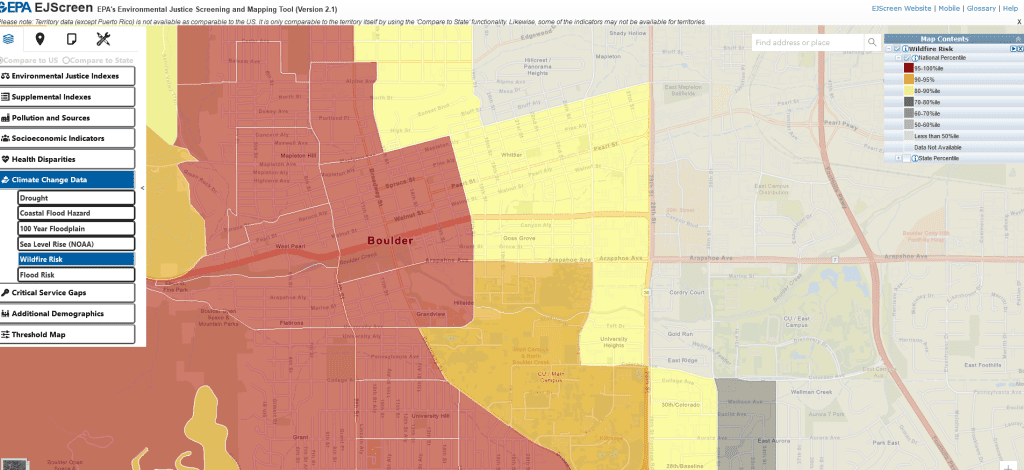

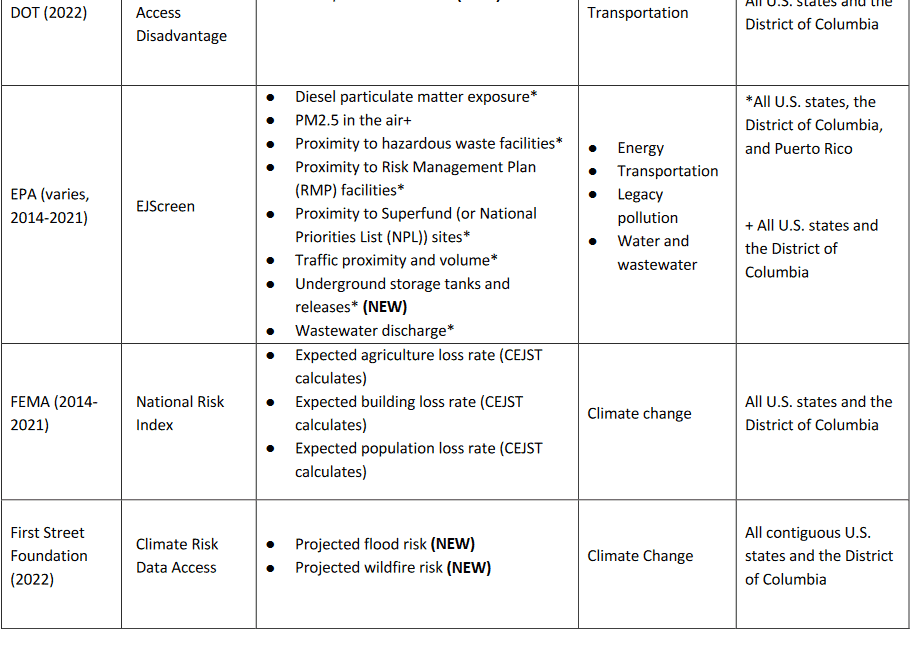

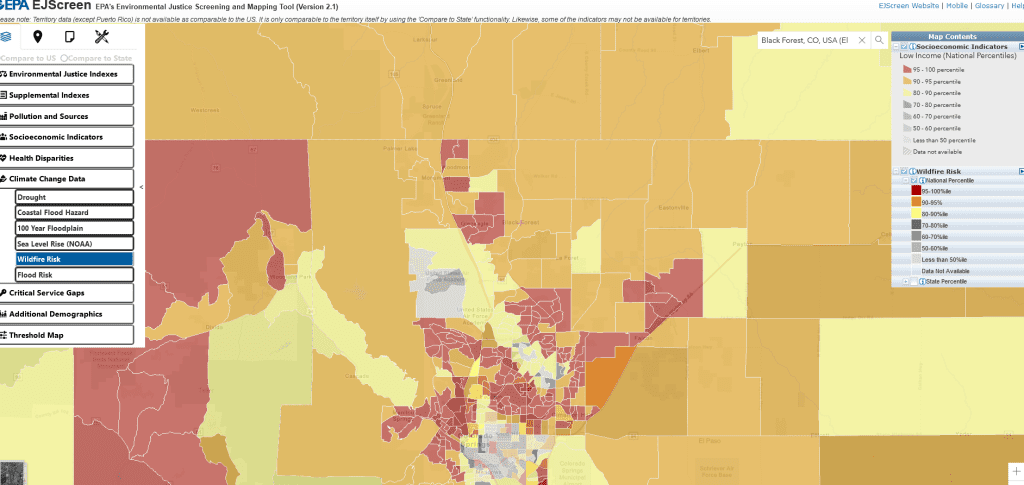

A 30-meter resolution model projecting the wildfire exposure for any specific location in the contiguous U.S., today and with future climate change. The risk of wildfire is calculated from inputs associated with fire fuels, weather, human influence, and fire movement. The risk does not consider property value.

Used in: Climate change category

Responsible party: First Street Foundation

Source: Climate Risk Data Access from 2022

Available for: All contiguous U.S. states and the District of Columbia

Both flood and fire risk take into account projected climate change- I couldn’t figure out which SSP is mapped in the CEQ EJ map. I found this update interesting from last year interesting..

The model update includes the migration from Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) to Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP), which allows for more precise assessments based on different climate scenarios. The Foundation is also expanding the flood and wind modeling to include multiple pathways, such as SSP 2-4.5 and SSP 5-8.5. Additional SSP pathways for wildfire and extreme heat scenarios are being developed for future releases this year.

I wonder whether new information about new mitigation, fuel treatment projects, etc. would show up in updates of the tool? I wonder whether it is updated? I think it’s a great idea to map the disadvantaged, but some of the criteria (not to speak of the ways the numbers are calculated) seem questionable. Given that poor people are less likely to be able to respond to any disasters, why not focus on that? And if the examples in the Forest Legacy are any indications, folks on the ground are quite capable of describing how their projects partner with Native Americans or help the poor.

As it turns out, the project scoring guide for FY 24 did not mention the maps

Benefits of projects for underserved communities and environmental justice initiatives should be highlighted where applicable. For example, benefits can be discussed within economic

benefits, water, cultural, public access, or climate resilience. Benefits for underserved communities can also be discussed in the Strategic section. Underserved communities: “underserved communities” refers to populations sharing a particular characteristic, as well as geographic communities, that have been historically underserved, marginalized, and adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality (pursuant to Executive Order 13985, Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government). Namely, these are Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and

queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality

From the “good government” perspective, I wonder whether a narrative addressed to those concerns may actually have better information than an un-updated map with unknown data quality. The best science and all that. It also sounds like looking it up on the EJ maps was an afterthought, and it turned out that the more local information actually led to “nearly 50%” being on the map.

But all agencies are apparently supposed to use this tool, according to the Q&A

The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the Climate Policy Office (CPO) released the Justice40 Interim Implementation Guidance on July 20, 2021. It directed agencies to develop interim definitions of disadvantaged communities. Agencies used their interim definitions during the tool’s beta phase. Agencies will now transition to using version 1.0 of the tool to geographically identify disadvantaged communities.

So I think most people are trying to do good things, and we disagree about how best to go about it. But using ungroundtruthed data and then telling agencies that they must use it instead of what they know in the real world seems problematic to me. There seems to be a tendency to centralize decisions based on broadscale “data” (the Satellite Gaze) and privileging that over local information. Often there is no transparent effort to ground-truth these maps. That would involve intentionally requesting feedback, posting the feedback, and discussing how that feedback was used to improve the models or data collection methodologies behind the map.

Choosing those sources of data and those manipulations can also centralize political power and decision-making, either in the name of efficiency or the name of “science.” What is the best data- for a given purpose, though, is ultimately a political decision. And just because data is available doesn’t mean that it’s good or relevant.

Finally, let’s circle back to the Keystone Agreements. Must they follow the Justice40 Initiative? How will we know if they do if the project data isn’t available?