At ground level, three family-held timber companies say the increasingly ferocious wildfires are transforming their businesses.

California’s first million-acre wildfire, the August Complex in 2020, burned through about 40,000 acres of Crane Mills holdings in the Mendocino National Forest. About 42% of those burned acres experienced total losses among young and old trees alike, meaning they will have to be wholly reforested or risk being overtaken by shrubs, Chief Financial Officer Drew Crane said.

The 2020 CZU Lightning Complex fires burned about two-thirds of Big Creek Lumber’s 8,000 acres of mixed redwood forests in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Company President Janet McCrary Webb — whose family members lost 16 homes — said though redwood trees have thick bark built to withstand wildfires, she remains unsure how many will succumb to fire damage and die.

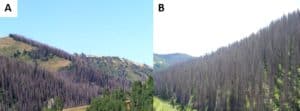

The Dixie Fire burned through about half of Collins Pine’s 95,300 acres around Lake Almanor in Plumas and Tehama counties. The company has found signs the fire was beneficial to some areas, but “about 30,000 acres is gone, black,” said Niel Fischer, Collins Pine western resources manager. More than 64,000 old-growth trees, the kind expected to survive wildfires, are probably dead, he said.

“I don’t want to use the word catastrophic, but it was catastrophic in terms of what it means to the business and what we have to do to recover,” Fischer said. “It shook us as foresters to our core.”

Wildfires are expected disturbances for California’s timber industry and are natural and restorative to these ecosystems. But the severity of fires in 2020 and 2021 is expected to result in significant destruction.

And they have to move fast to harvest the charred trees. Dead and dying trees can be milled for lumber, but it has to be done within about two years before they rot or become infested with insects.

Crane Mills, based in Corning on the western side of Tehama County, is running its mill at full tilt. But the company lost a key buyer of Ponderosa pine in March — there is simply too much wood.

“There aren’t enough loggers, there aren’t enough trucks, there aren’t enough foresters,” Crane said. “A lot of it will go to waste.”

Fischer said it’s not like losing one year’s tomato crop — rather Collins Pine has 10 or 15 years worth of resources “dead on the stump.”

“Dead trees do have value in the forest as long as you don’t have too many,” Fischer said. “We are careful to conserve trees that have died so they’re naturally incorporated into soil and become habitat … but there has to be balance.”

George Gentry, senior vice president of the California Forestry Association, said salvage logging operations can offer an economic boost in the immediate aftermath of a wildfire, but not enough to compensate for the long-term impact he expects will dampen timber harvests “for decades to come.” Gentry estimated 1.6 billion board feet burned this year — more than the 1.5 billion board feet produced each year across the state.

“They’ll do some initial salvage, they’ll do some initial rehabilitation, then they’ll have to pull back,” Gentry said. “If they reduce mill employment, if they reduce purchases, if they reduce anything they’d buy locally, that impact is really significant in rural economies.”

McCrary Webb with Big Creek Lumber said the volume of dead, dying and drying trees throughout Northern California forests should be a concern for all — and she hopes to see more solutions, like an increase in demand for wood biomass energy production.

“That’s one of the issues we see that really the whole state has to grapple with: How can you effectively deal with all this wood?” McCrary Webb said. “A lot of this wood, there’s no place to take it. Some were taking it to landfills. There’s no place for it to go.”

Collins Pine has been a pioneer in uneven-age harvesting, a way to manage commercial forests so they have a diversity of tree species and ages, as in natural ecosystems, Fischer said.

He said that while some portions of the land will rebound, they expect a lot of it will have to be wholly replanted. That “zeroes out the clock” for a forest meant to have both old and young trees, he said. Decades later, portions with same-age trees would be harvested at once — essentially clear-cut, a major shift away from their efforts to steward timber to more closely resemble natural forest ecosystems.

Crane said the August Complex fires were a “seminal event” for his family’s company, forcing it to rewrite its 100-year business plan. It too is facing a shift from uneven age reforestation practices to tree plantations, he said.

“You’re planting an even-aged forest — and I’m not sure how fire-resilient that is,” Crane said.

In 2020 alone, about 1 million acres changed from living forest to dead forest because of wildfires, said Joe Sherlock, regional silviculturist for the U.S. Forest Service in California. The Forest Service manages 8 million acres in California, roughly one-quarter of the state’s forestland.

Salvage timber sales are critical to funding reforestation and preventing dangerous fuel loads from building up and providing tinder for the next fire, Sherlock said. But the sheer scale of severe, tree-killing fires is adding pressure to an already overburdened system. There simply aren’t enough mills to process the trees or buyers to take the lumber.

“I worry about that a tremendous amount,” Sherlock said. “It will be expensive to gather that material up and create a hospitable environment for seedlings. I don’t know whose checkbook we can use.”

Brad Seaberg, who manages timber sales in California for the Forest Service, said this year’s fires are “testing the market” for whether the agency can find enough purchasers for the amount of lumber available on federal land. And a significant number of smaller-scale landowners affected by wildfires have also entered the timber market, he said.

“The scope of what’s going on is overwhelming,” Seaberg said.

But not everyone sees salvage logging as a boon to forest health or the best defense against the next fire.

Ernie Niemi, an Oregon forest economist who has studied timber practices for decades, said salvage logging on Forest Service land comes with steep costs, both financial and environmental. Niemi said dead trees hold greater benefit in the environment as crucial storage for climate-warming carbon dioxide and habitat for woodpeckers, insects and other species.

“Those dead and dying trees out on the landscape are not suddenly worthless from an ecological perspective,” Niemi said. “That big trunk still holds an awful lot of carbon.”

Sherlock said that is true for areas with a smattering of dead trees amid a rebounding forest. But he said large areas of mostly dead forests are less likely to naturally reseed and risk conversion from forest to shrubland. Harvesting dead or dying trees is necessary work, he said.

“You can imagine what it would be like to ignore all of those standing (dead) trees,” Sherlock said. “As the years go by, more and more of those trees will snap off or tip over, all on the ground. Can you imagine a forest with tons of tons of dry wood ready to burn in the next fire?”

An earlier version of this story misstated the volume of timber burned this year and produced annually on average in California. It is in billions of board feet.