Matthew posted this about litigation on the Rio Grande plan.

The Canada lynx relies heavily on the Rio Grande National Forest in the Southern Rocky Mountains, which contains more than half the locations in Colorado where lynx are consistently found. But the population is in dire straits, and federal scientists predict that the lynx may disappear from Colorado altogether within a matter of decades. The Forest Service’s new plan has now opened the extremely important lynx habitat in the forest to logging, one of the biggest threats to the cat.

“Scientists are saying the Canada lynx population in the Rio Grande National Forest is in the ‘emergency room,’ but the Forest Service refuses to provide this species with the care it needs,” said Lauren McCain, senior policy analyst for Defenders of Wildlife. “

Since CPW monitors lynx populations, I called them and found that the total lynx population in Colorado is actually stable based on their monitoring. So to say in Colorado RG pops are in “dire straits” does not appear to be accurate, unless there is info somewhere that the RG population is in decline, but it averages out because other pops are expanding (?). It also seems like the LCAS (the statewide lynx forest plan amendment), which has been in existence since 2008, would still be in place under the new RG plan. So if that’s the case (CPW is not the “logging industry” and lynx isn’t hunted, so shouldn’t we trust them?), why would “federal scientists” make those predictions about the species as a whole disappearing from Colorado? Climate change? And yet, if that were the case, why choose southern Colorado for lynx reintroduction? (that was in 1997, so that wasn’t as much of a concern as today).

But.. if you reintroduce species to the southern part of their range, that depend on snowpack during the winter, and then they ultimately have trouble from climate change..is the solution to stop logging? Even with LCAS in place? Ultimately then, it could be argued that anything that disturbs lynx is a threat, and on that basis should be stopped, including, possibly, recreation of all kinds. And yet, with current levels of all those activities, numbers of the species state-wide have remained stable. But we need to do more protective habitat interventions even so, just in case? And what if at the end of the day, we have kept everyone out (and removed developed ski areas) and the lynx still moves north due to climate change?

Here’s the history from CPW:

Colorado represents the southern-most historical distribution of naturally occurring lynx, where the species occupied the higher elevation, montane forests in the state (U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2000). Lynx were extirpated or reduced to a few animals in Colorado, however, by the late 1970’s (U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2000), most likely due to multiple human-associated factors, including predator control efforts such as poisoning and trapping (Meaney 2002). Given the isolation of and distance from Colorado to the nearest northern populations of lynx, the Colorado Division of Wildlife (now Colorado Parks and Wildlife [CPW]) considered reintroduction as the best option to reestablish the species in the state…

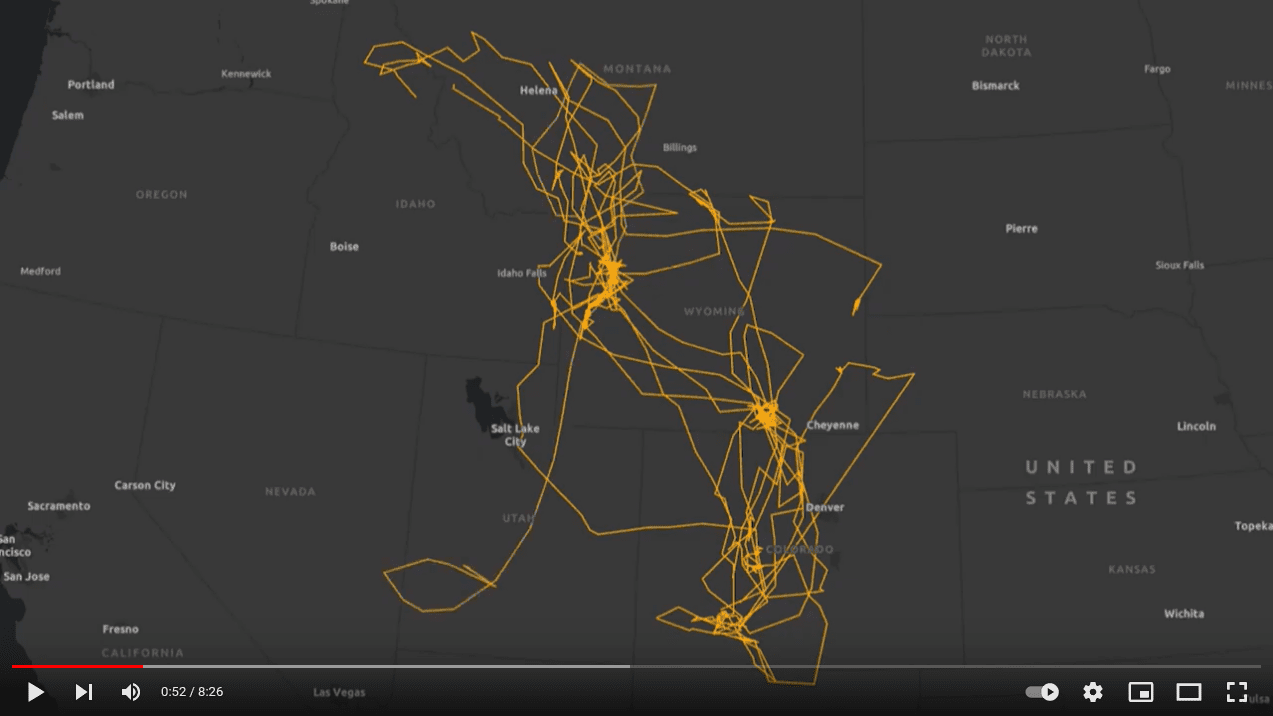

The DOW’s strategy for lynx reintroduction was to first release a number of lynx within a “core reintroduction area” in southwestern Colorado that biologists regarded as the best potential lynx habitat available in the state. Biologists hoped that over time lynx would not only remain in this area long enough to survive and reproduce, but also disperse on their own into other tracts of suitable habitat throughout the state. To this end, DOW biologists began releasing lynx back into southern Colorado in 1999 (Fig. 1). During 1999−2006, a total of 218 wild-caught lynx from Canada and Alaska were released in this core area.

Most interesting to me was this video on Colorado lynx, full of information about them and their lives, plus lots of photos and videos, and their summer explorations, as well as research on lynx and bark beetles, winter recreation, and snowshoe hare density, with CPW scientist Jake Ivan. If you’ve seen a lynx way outside of its habitat during the summer, you might not be imagining things; they go on long walkabouts (to Idaho, Montana and out east) and come back for winter. It’s amazing to me that the telemetry gear does not interfere with lynx activities.

Here’s a link to my previous post on the CPW/FS winter recreation research. I just noticed I hadn’t posted the paper then, here’s a link to an article and several papers.

*************************************************

For more detail, here’s what the ROD for the new RG Forest Plan says about LCAS (page 29 of the ROD):

Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment

The selected alternative uses direction in the Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment Record of

Decision, as amended and modified. The Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment was completed

prior to the spruce beetle infestation and accounts for live, green forested habitat. Standards

VEG S7 (S-TEPC-2) and S-TEPC-3 were added to the land management plan to account for

the increased amount of standing, dead spruce-fir habitat.

The direction incorporates the most recently available information from a study on the use of

habitat by lynx on the Forest (Squires et al. 2018). The direction applies to lynx habitat on

National Forest System lands on the Rio Grande National Forest.

Canada lynx habitat in Colorado primarily occurs in the subalpine and upper montane forest

zones. Lynx show a preference for subalpine fir, Engelmann spruce, aspen, and lodgepole

pine forest types. Recent information demonstrates the close relationship of lynx on the

Forest to particular locations within the subalpine forest zone and their use of specialized

forest structure (Ivan et al. 2014, Squires et al. 2018). Other habitats used by reintroduced

lynx locally include spruce-fir/aspen associations and various riparian and riparian-associated

areas dominated by dense willow, particularly during the summer period (Shenk 2009).

The Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment identified four linkage areas on the Forest that

remain important areas of habitat connectivity. Connective habitat in the San Juan Mountains

is essential for facilitating movement of Canada lynx across the landscape. The plan provides

forestwide plan components that protect connectivity.

This direction identifies the high probability lynx use areas for the Forest and clarifies that

VEG S1 and VEG S2 from the Southern Rockies Lynx Amendment do not apply in lynx

analysis units outside the high probability lynx use areas. Standard VEG S7 provides

direction for salvage activities that occur in the high probability lynx use areas.

The biological opinion concluded that the direct, indirect, and cumulative effects of the land

management plan are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of lynx within the

contiguous United States distinct population segment. Endangered species implementing

regulation (50 CFR 402.14 (i)(6) does not require an incidental take statement for

programmatic level planning. Any incidental take resulting from any action subsequently

authorized, funded, or carried out under the program will be addressed in subsequent section

7 consultation, as appropriate.