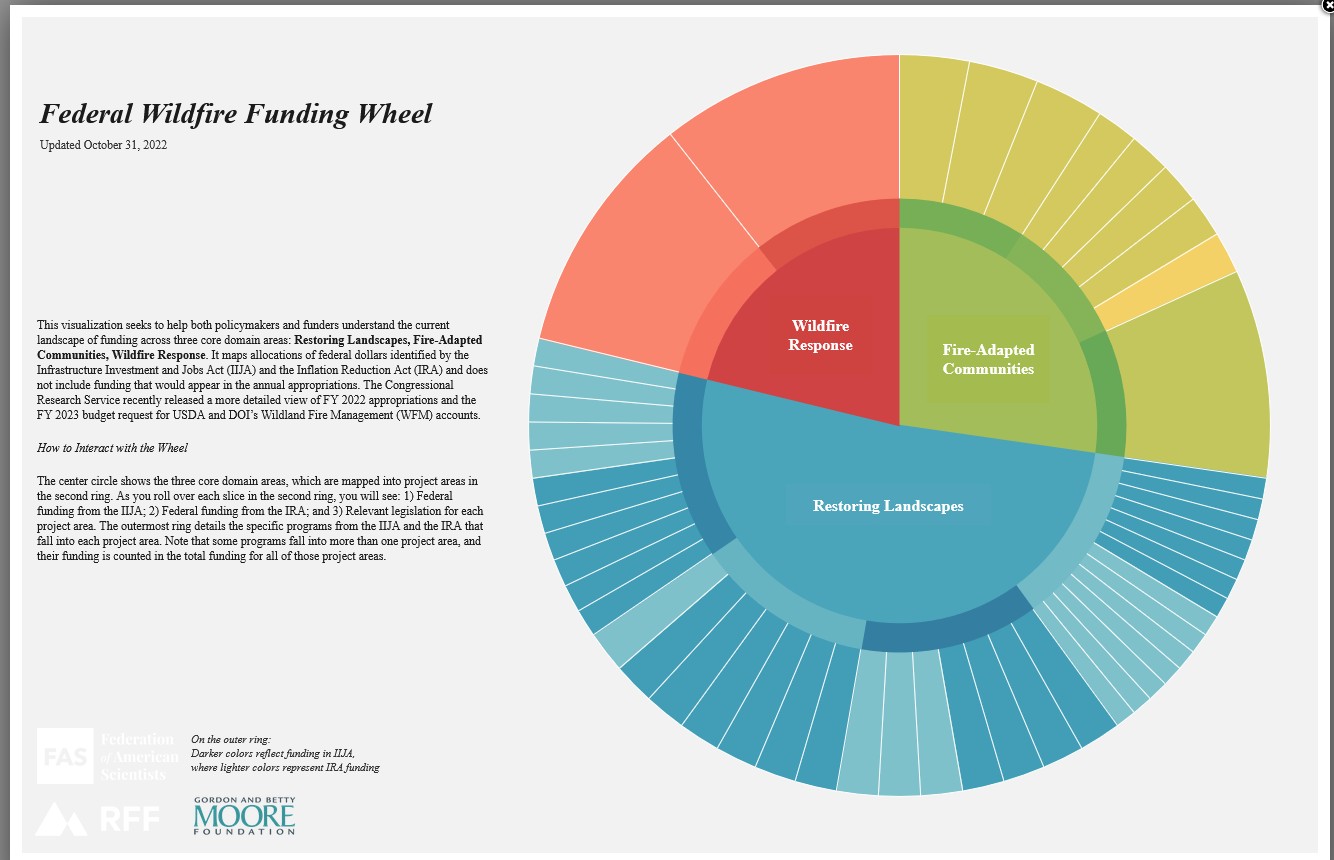

This is a pretty cool thing developed by the Federation of American Scientists, Resources for the Future, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. If you click on the link (not the photo above) you can see all the different programs. Lotsa bucks.

Budget

Question About Forest Service Budget and R&D

A reader asked:

I had a question about the FY 2024 budget (which is recently approved) and the impacts on USFS Research Stations and R&D. It seems like there is a hiring freeze in at least some (if not all) research stations, and it seems like the discussion is that this is a result of some combination of budget shortfalls in the budget (a small cut) as well as some allocation issues within the Budget Modernization efforts. Does anyone know what is happening here, and if hiring will be starting again anytime soon?

I was also wondering, in a possibly related question, because the Trout Unlimited Keystone Agreement included that TU could be paid to:

• Developing the science and tools to address high priority concerns such as climate change, impacts of energy development, restoration of degraded habitats and populations, and control of aquatic invasive species,

It used to be that R&D dollars were said to be necessary for “the science” but I’ve been assured that NFS funds are fine to use for this nowadays.

People with information can post here or contact me directly. I will respect your anonymity.

Appropriations News: Wildland Firefighter Pay Raise Preserved

Many thanks to a TSW reader for this!

Here’s what’s in the first spending package from E&E News:

Lawmakers released final fiscal 2024 bills Sunday for most of the federal government’s energy and environment programs.

Interior, natural resources Even though overall discretionary spending at Interior would remain roughly the same, lawmakers took a knife to several of its bureaus. The Fish and Wildlife Service would see a $51 million cut, the National Park Service a $150 million drop and the Bureau of Land Management an $81 million reduction, lawmakers said in summaries.

The bill would cut allocations for BLM’s renewable energy programs by $1.6 million — to $39.3 million from $40.9 million enacted for fiscal 2023. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is in line for a $28 million cut. The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement would get $18 million less. The U.S. Geological Survey would see $42 million below fiscal 2023 levels, and the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement would get $18 million less. The package includes $141.9 million for BLM’s contentious wild horse and burro program, less than either the Biden administration’s request or last year’s level of $148 million.

Even with the widely distributed cuts, congressional Democrats said they were relieved to have fended off more dramatic reductions initially sought by Republicans. “We keep our promises to brave wildland firefighters and protect vital investments to stay the course on historic climate action taken by the Biden administration while safeguarding our public lands,” Murray said. As for riders, the House Republicans’ original plan would have blocked the Fish and Wildlife Service from implementing the rule that moved the northern long-eared bat from threatened to endangered status. The final package opted instead for language acknowledging the “on-the-ground impacts” of ESA listings and urging the agency to “continue to collaborate” with states, local communities and others on “improving voluntary solutions to conserve species.”

Lawmakers also gave FWS and the park service instructions to provide an “in-depth” briefing regarding plans to reintroduce grizzly bears into the North Cascades region of Washington state. The package includes language that would prohibit the Interior Department from listing the greater sage grouse for protection under the Endangered Species Act. This rider has been inserted into every Interior funding bill since fiscal 2015

Forests, wildfire The Forest Service would receive just over $6 billion in discretionary spending, which appropriators said would preserve the pay raise wildland firefighters first received in fiscal 2023. Wildfire suppression would be funded at $4 billion, of which $2.65 billion would be in the off-budget wildfire disaster fund established by Congress in 2018. The bill includes $175 million for hazardous fuels reduction in national forests, such as thinning vegetation. That’s a reduction of $31 million, according to budget documents. Lawmakers also asserted in a joint explanatory statement that wood gained from forest thinning can qualify as renewable biomass under the federal renewable fuel standard

Agriculture The Agriculture-Rural Development bill, with more than $26.2 billion in discretionary spending for the Department of Agriculture and related agencies, reflects a slight increase from USDA’s fiscal 2023 level. Even though the legislation would boost agricultural research programs, it would shave some conservation efforts. The Natural Resources Conservation Service would receive $951 million, down from $1.03 billion in fiscal 2023, and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture would see a $22 million reduction, to $1.68 billion, according to budget documents. Republicans said the NIFA reduction would maintain funding for top priorities and reduce it for “several low-priority research programs.” And they won a provision rejecting the NRCS’s use of funds for equity initiatives, which the Biden administration says help farmers from historically disadvantaged groups that may have been denied agency loans in the past, for example. The Agricultural Research Service would see a $44 million increase, to $1.79 billion. Lawmakers decided that additional research funds should go to matters including soil health, effects of wildfire smoke on wine grapes and other specific areas. Appropriators agreed to a Republican-led provision blocking the USDA from expanding staff in the nation’s capital and instead instructed the department to report on how to improve staffing levels in field offices of the NRCS and other agencies. And while the agreement doesn’t include an effort by House Republicans to heavily cut the Rural Energy for America Program, it does call for a rescission of $10 million from prior appropriations.

**********

“Appropriators agreed to a Republican-led provision blocking the USDA from expanding staff in the nation’s capital and instead instructed the department to report on how to improve staffing levels in field offices of the NRCS and other agencies.” I wonder if that applies to the FS, since the FS is under Interior Approps?

Friday News Roundup I. Forest Service Funding and Belt-Tightening

Rumors of OIG Report on FS Spending on the Infrastructure Act

There are rumors of an OIG report that talks partially about the Keystone Agreements that the FS uses to help with BIL and IRA efforts.

I am finding out more about these agreements to report on here.

My current understanding is that large sums of money could go through these agreements, but actually don’t until a specific project is funded. So the FS doesn’t have to “claw back” money because most was never sent out. Which goes to..

FS Funding Shortfall Possibilities and Plans

The Hotshot Wakeup has a story on the FS not having enough money, or tightening their belts due to lower appropriated funds in 2024, 5.2% cost of living adjustment and inflation.

Here’s the Chief’s letter.

I also heard that there are 33K permanents now, at least in part, due to fire positions going from temporary to permanent seasonals 13/13 or 18/8, which costs more due to benefits. The idea, of course, is that life for these folks will be better under better employment conditions and more people will want to work, and fewer people leave. My understanding is that that (33K) is more than the FS has had in previous years, but I can’t recall the exact figures by year.

I’m hoping commenters can add more context and background.

Turning an Aircraft Carrier? Report on Senate Farm Bill and Approps Hearing: Guest Post by Dave Mertz

Note from Sharon: There’s all kinds of topics (porky and non) at this hearing- from firefighter mental health to a climate “hub” in Hawaii. Please add your own observations and interesting news takes in the comments.

Congressional Hearings for the Farm Bill and Agency Appropriations Watching congressional hearings is a really interesting way to find things out that you may otherwise never hear about. Over the past couple of months, there

have been Senate hearings for the Farm Bill with Associate Chief Angela Coleman, and Senate Appropriations hearings with Chief Randy Moore. I found the April 18 th “Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources about the FY2024 budget request for the Forest Service” Chief Moore testimony: to be particularly interesting.

A common theme of all of these hearings is holding the Forest Service accountable to increase timber outputs. Numerous bills have been proposed to hold the Forest Service’s feet to the fire. Too many to even mention here. It’s

interesting that this interest in accountability is coming from Republicans, Democrats and an Independent. They all want to know what the Forest Service is doing with the billions of dollars that have been appropriated to them in the recent past, and why timber outputs have not seen a resulting increase. They all express a concern in dealing with the wildfire crisis.

Chief Moore primarily gives three reasons why there has not been a dramatic increase and why the timber volume sold target was not met last fiscal year. Now, we all know the old metaphor that you don’t turn an aircraft carrier on a dime, and in this instance, the Forest Service is the aircraft carrier. Chief Moore says that both wildfires and storms wreaked havoc on areas that were planned for timber sales, and this drastically impacted their target accomplishment.

He went on to say that they are having real difficulty in hiring. The process is not working well and continues to be cumbersome. Also, they are losing employees through attrition, almost as quick as they can hire them. He provides several reasons for this, that pay levels are a problem as well as housing in the locations where they need people to work. It’s interesting that Chief Moore did not mention NEPA and lawsuits as reasons for the lack of target accomplishment.

Is it finally time to admit that the Albuquerque Service Center was a big mistake? Before ASC, the Forest Service had a relatively well-oiled hiring machine. I believe it could have held its own in comparison to most other Federal Agencies. Chief Moore oversees ASC, if it has serious problems then he needs to fix it. It would take a lot to finally admit that ASC was a mistake, but maybe that is what needs to happen. With regards to housing, the Forest Service used to be in the business of providing housing, but then it was seen as time to move on from that. Much of the government housing was sold off. Now that is not looking like such a great decision.

Chief Moore says that they have a plan to get up to 4 billion board feet by FY 2027. Sen. Angus King from Maine stated that Eisenhower took Europe in 11 months, why would it take the Forest Service so long to get to 4 billion board feet? Interesting question. It’s also interesting that almost all of these Senators expressed concerns about wildfires but there was little said about increasing prescribed fire and pre-commercial thinning. If they were truly interested in reducing wildfire threats, there could be a whole lot of mitigation through those two methods in comparison to cutting sawtimber-sized trees.

The Forest Service is in a tough spot. For years they stated that if they were just provided with enough money (Chief Moore states that they still need more) they could address the wildfire crisis. Just like the dog who never expected to catch the car, and when they finally did, they didn’t know what to do with it. Chief Moore received some hard questions in this hearing. I felt a little sorry for him. He can’t pull a rabbit out of a hat and fix the wildfire crisis overnight, but the Forest Service needs to be upfront about what they can actually do and what the realistic timeframes will be.

Dave Mertz retired from the Black Hills National Forest in 2017 as the Forest’s Natural Resource Staff Officer. Over the course of his career with the FS, he was a Forester, Silviculturist, Forest Fire Management Officer and a Fire Staff Officer. Since retirement, he has stayed involved in Forest Management issues, with a particular interest in the Black Hills NF’s timber program

193+ From Timber Service to Fire Service: The Evolution of a Land-Management Agency by Andy Stahl

A while back, a commenter asked for (if I remember correctly) visions for the future of the Forest Service. I thought back to the book “193 Million Acres: 32 Essays on the Future of the Agency” edited by our own Steve Wilent (and with essays by many TSW writers and friends). It was published in 2018, which means we wrote our essays before that, and much has happened since. The Infrastructure Bill, Covid and Covid-Enhanced Recreation, the 10-year Implementation Strategy, and so on. So I asked the authors if they would be willing to share the main ideas of their essays, and any updating thoughts they had, in a post on TSW.

I’d also like to invite others to contribute to this series, which I’ll call 193 Million Acres Plus. I’d especially like to hear from current employees, and anonymous submissions will be accepted/encouraged because we’re interested in any ideas attributed to specific people or not. A final suggestion, please don’t just talk about the problems, dream and vision some solutions. And with that, to Andy Stahl’s 193+ essay.

From Timber Service to Fire Service: The Evolution of a Land-Management Agency

Andy Stahl

In 2017, the US Forest Service set an enviable record. For the first time in its history, it spent more than $2 billion fighting fires. The $2.4 billion spent in 2017 (exceeded the next year at $2.6 billion) is more than twice the Forest Service’s average annual spending during the 2000s and seven times the 1990s average. To put the increase into perspective, it’s double the government-wide increase in discretionary nondefense spending. Firefighting has gone from 15 percent of Forest Service spending in the 1980s to more than 55 percent today.

Why and how did this occur, and what are the implications for the Forest Service and our national forests? The answers are 1) because the Forest Service needed to replace rapidly declining timber revenue; 2) because it could; and, 3) budgetary casualties for everything else the Forest Service does.

In 1908, Gifford Pinchot asked Congress to authorize the Forest Service to borrow money from “any appropriation … for fighting forest fires in emergency cases.” Pinchot wanted his field foresters to be able to pay the needed men from locally available government money, from such sources as receipts collected from ranchers or from the occasional sale of timber, and not wait the several weeks or months for a proper check to be cut from the head office. A reluctant Congress agreed, although the authority it granted was less than Pinchot sought (Pinchot also asked to cover costs associated with non-fire emergencies, too, for example, replacing a washed-out bridge, but Congress refused). A parsimonious Congress also made sure the Forest Service accounted for every penny by requiring that “detailed accounts arising under such advances shall be rendered through and by the Department of Agriculture to the General Accounting Office.”

For the first half of the 20th century, borrowing from non-fire accounts to pay for wildfire suppression followed the model Pinchot outlined. Borrowing was minimal, because Forest Service local offices had little cash on hand to advance for firefighting purposes. The post–World War II logging boom changed the income statement, however. Annual logging revenue grew from $20 million between 1946 and 1950, to $140 million between 1961 and 1965. Harvest income climbed meteorically in the 1970s to almost $1 billion by that decade’s end. By the end of the 1980s, the Forest Service was regularly exceeding the $1-billion mark, with timber-harvest income peaking in 1989 at $1.3 billion.

Divvying up this financial windfall proved a challenge. A 1908 law allocated 25 percent of the cash to the state where the timber was cut; these funds were earmarked for building roads and financing schools. A 1913 law allowed the Forest Service to keep 10 percent for road construction and maintenance. Thus, 65 percent of the Forest Service’s timber revenue was returned to the US Treasury, where it would be available for Congress to spend as it saw fit. In the eyes of cash-strapped Forest Service managers who had done the hard work, this seemed an unfair, if not wasteful, outcome. Providently, a 1930 law called the Knutson-Vandenberg (K-V) Act offered a solution.

The K-V Act authorized the Forest Service to retain timber-sale receipts for reforestation and other improvement work on cut-over land. In the early years, when sale receipts were small, this authority provided modest revenue and was exercised conservatively. With the growth of logging, however, the K-V dollars retained grew in absolute and percentage terms. Through 1975, the Forest Service had deposited about 10 percent of timber-harvest revenues into its K-V fund. The K-V fund grew, but only proportional to the increased timber-sale level and associated cost of reforesting the increasing number of cut-over acres. Nonetheless, some states, especially Oregon, became concerned that the K-V fund’s growth was coming at the expense of the 25 percent of revenue to which states were entitled (states were paid 25 percent of receipts net of K-V withdrawals). In 1976, as part of the National Forest Management Act, Congress amended the revenue-sharing law to require that 25 percent of gross sale receipts, including the K-V charges, be paid to states.

From 1976 on, with the states’ 25 percent funds now protected, the Forest Service began diverting an increasing percentage of timber-sale revenue to its K-V fund, from 10 percent in the 1970s to 30 percent of every timber dollar by the end of the 1990s. The K-V fund grew accordingly, increasing from an annual average of $21 million in the 1960s, to $61 million in the 1970s, to $176 million in the 1980s, peaking at $269 million in 1993. In 1991, the Forest Service’s creative financing gurus began dipping into the K-V fund to pay for firefighting costs, too. After all, the Forest Service was using K-V to pay for a bit of everything else, why not firefighting? Pinchot’s 1908 law offered the legal loophole to do so, and the K-V cash reserves were huge, albeit also over-obligated to pay for future reforestation, a concern the General Accounting Office raised in the mid-1990s.

Timber Harvesting Decline

Then the wheels came off. The 1990s lawsuits aimed at protecting northern spotted owl habitat slashed logging levels by 90 percent in the productive Pacific Northwest states, which accounted for a 40 percent drop nationwide. Add in protections for the bull trout, grizzly, and the northern spotted owl’s California and Mexican cousins, and, with the exception of the small east-of-the-Mississippi national forests, the agency’s timber program all but died, dropping from a high of 12 billion board feet annually to an annual three billion board feet over the last 20 years. So, too, the K-V revenue stream dried up. The Forest Service faced a budget nightmare the likes of which it had never seen. Congressional appropriators had grown used to a substantially self-financed Forest Service. Firefighting costs had become no concern to the bureaucracy, which had grown accustomed to a substantial off-budget expense account.

The Clinton administration chose to backfill this gaping financial hole by doubling down on firefighting. In 2000, Clinton’s National Fire Plan provided the justification for a new national forest raison d’être that was all about fire, all the time. Put out fires, light fires, clear fire-prone brush, thin forests overstocked because of a lack of fire, repair forests and watersheds damaged by too much fire, restore fire-dependent ecosystems, write fire-management plans and community fire-protection plans, map wildland-urban interfaces and fire-regime condition classes, buy more fire trucks, lease more air tankers, hire more firefighters. Recruit non-governmental allies by linking fire to climate change (to enlist environmental support), and by linking fire to a lack of active management (to enlist timber industry support). For its own financial survival and to stave off painful cuts to its workforce, the Timber Service became the Fire Service.

This strategy proved astonishingly successful. Forest Service spending is greater than it has ever been. But it’s not the same agency as 30 years ago when timber ruled the roost. Half of the Fire Service’s workforce are firefighters; most are not college-educated. More than half of the Forest Service’s budget is spent fighting fire, a disproportion that exceeds the timber era. But, for a bureaucracy committed to its own survival and growth, it’s a remarkable success story.

The Forest Service, however, tells a different story. It claims that over-grown forests—a result of too much fire suppression—and a hotter climate justify its runaway firefighting costs. But those arguments don’t explain why other wildland firefighting agencies have not incurred the same galloping rate of cost inflation. California leads the nation in the growth of homes in wildland-urban interface zones. Although the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire), which bears the cost suppressing wildland fires on private land, has seen its fire-suppression costs rise, its increases are much less than the Forest Service’s. CalFire’s four-fold rise since the 1990s is substantially less than the Forest Service’s seven-fold increase, and CalFire’s 30 percent increase in costs during the 2000s is less than one-third of the Forest Service’s 100 percent increase over the same period. The Department of the Interior, which manages 500 million federal acres compared to the Forest Service’s 156 million, has had firefighting cost increases of 3.3-fold compared to those of the 1990s, less than half the Forest Service’s seven-fold increase, and a 10 percent increase in the 2000s, one-tenth the Forest Service’s 100 percent rise.

Proposals to “fix” the Forest Service’s fire spending have focused on begging Congress for more money. These pleas were answered in late 2017 with half billion more dollars appropriated for firefighting. While not the “disaster spending” checkbook (unregulated by congressional spending caps) the Forest Service has sought, it’s better than a poke in the eye with a sharp stick. Meanwhile, the steady shrinkage of money to manage recreation, fish, wildlife, and water continues.

The Forest Service’s firefighting costs will continue to go up so long as Congress is willing to pay the tab. Beginning in 2020, and for the first time in its history, the Forest Service had access to off-budget “disaster” spending authority. These spending increases will occur not because there are more fires—fire ignitions have gone down steadily on the national forests for the last 30 years. And not because more acres are burning—acres burned show no clear trend over the past century. The Forest Service will continue to spend more money fighting fires because fighting fire pays its bills.

The Infrastructure of Infrastructure: Wildfire Commission, Fuelbreak System and Plans for Spending $

Most of the articles I’ve read on the Infrastructure Bill talk about the bucks, and that’s certainly the most important thing. Still, with the Reconciliation Bill potentially adding more bucks into the spending pipeline, it’s also interesting to look at provisions that talk about structures for spending the money, or what we might call the Infrastructure of Infrastructure. What is also of interest is that while we’ve discussed the potential differences between restoration, hazardous fuel treatments, and fuel break projects, Congress is pretty careful in delineating each pot of money.

1. Developing a Fuelbreak system

Section 40803(i) requires a Wildfire Prevention Study of the construction and maintenance of a system of strategically placed fuelbreaks to control wildfires in western States. Upon completion of the study, the Secretary of Agriculture is required to determine whether to initiate a programmatic environmental impact statement to implement the system of strategically placed fuel breaks.

What we might find interesting about this is that it separates out fuelbreaks… the realm of fire suppression practitioners and fire scientists, and gives them their own space and planning without also needing to consider “restoration” NRV and other concepts (which have a separate pot). As to the programmatic EIS; many NEPA practitioners have not found these to be all that helpful. If litigatory groups don’t like the project, they get two bites at the litigatory apple (one programmatic and one project). There’s also the problem of analyzing and getting through a PEIS with accompanying litigation in five years, let alone any subsequent project NEPA. I still think an all-lands approach at perhaps a multiforest scale, and a site-specific EIS (for strategic fuelbreak establishment and maintenance) would be a better and faster way to go.

2. A Joint Plan for spending the money; hopefully before too much is spent.

Section 40803(j) requires USDA and DOI to establish a 5-year monitoring, maintenance and treatment plan that describes the how both will use the funding in subsection (c) to reduce the risk of wildfire and improve the Fire Regime Condition Class of 10,000 acres of Federal, Tribal or rangeland that is at very high risk of wildfire. Not later than 5 years after enactment, USDA and DOI are required to publish a long-term strategy to maintain forest health improvements and wildfire risk and to continue treatments at levels necessary to address the 20M acres needing priority treatment over the 10 year period post publication of the strategy.

I like how both 1 and 2 acknowledge not only what it takes to treat, but also to maintain.

5) the Wildfire Commission (section 70201)

ESTABLISHMENT.—Not later than 30 days after the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretaries shall jointly establish a commission to study and make recommendations to improve Federal

policies relating to—

(1) the prevention, mitigation, suppression, and management of wildland fires in the United States; and

(2) the rehabilitation of land in the United States devastated by wildland fires.…

DATE.—The appointments of the members of the Commission shall be made not later than 60 days after the date of enactment of this Act.

The composition is fairly complex but appears to be about 11 feds and 18 others. The two secretaries are joint co-chairpersons. Ideally it will be a good way to highlight problems and improve, whilst avoiding partisanizing the issues- and yet having enough political oomph to get things done. Below is their list of things to do..

(1) IN GENERAL.—Not later than 1 year after the date of the first meeting of the Commission, the Commission shall submit to the appropriate committees of Congress a report

describing recommendations to prevent, mitigate, suppress, and manage wildland fires, including—

(A) policy recommendations, including recommendations—

(i) to maximize the protection of human life, community water supplies, homes, and other essential structures, which may include recommendations to expand the use of initial attack strategies;

(ii) to facilitate efficient short- and long-term forest management in residential and nonresidential at-risk areas, which may include a review of community wildfire protection plans;

(iii) to manage the wildland-urban interface;

(iv) to manage utility corridors;

(v) to rehabilitate land devastated by wildland fire;

and

(vi) to improve the capacity of the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of the Interior to conduct hazardous fuels reduction projects;

(B) policy recommendations described in subparagraph

(A) with respect to any recommendations for—

(i) categorical exclusions from the requirement to prepare an environmental impact statement or analysis under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969

(42 U.S.C. 4321 et seq.); or

(ii) additional staffing or resources that may be necessary to more expeditiously prepare an environmental impact statement or analysis under that Act;

(C) policy recommendations for modernizing and expanding the use of technology, including satellite technology, remote sensing, unmanned aircraft systems, and

any other type of emerging technology, to prevent, mitigate, suppress, and manage wildland fires, including any recommendations

with respect to—

(i) the implementation of section 1114 of the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act (43 U.S.C. 1748b–1); or

(ii) improving early wildland fire detection; (D) an assessment of Federal spending on wildland fire-related disaster management, including—

(i) a description and assessment of Federal grant programs for States and units of local government for pre- and post-wildland fire disaster mitigation and

recovery, including—

(I) the amount of funding provided under each program;

(II) the effectiveness of each program with respect to long-term forest management and maintenance; and

(III) recommendations to improve the effectiveness of each program, including with respect to the conditions on the use of funds received under the program; and

H. R. 3684—827

(bb) the extent to which additional funds are necessary for the program;

(ii) an evaluation, including recommendations to improve the effectiveness in mitigating wildland fires, which may include authorizing prescribed fires, of—

(I) the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program under section 203 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5133);

(II) the Pre-Disaster Mitigation program under that section (42 U.S.C. 5133);

(III) the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program under section 404 of that Act (42 U.S.C. 5170c);

(IV) Hazard Mitigation Grant Program postfire assistance under sections 404 and 420 of that Act (42 U.S.C. 5170c, 5187); and

(V) such other programs as the Commission determines to be appropriate;

(iii) an assessment of the definition of ‘‘small impoverished community’’ under section 203(a) of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency

Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5133(a)), specifically—

(I) the exclusion of the percentage of land owned by an entity other than a State or unit of local government; and

(II) any related economic impact of that exclusion;

and

(iv) recommendations for Federal budgeting for wildland fires and post-wildfire recovery;

(E) any recommendations for matters under subparagraph

(A), (B), (C), or (D) specific to—

(i) forest type, vegetation type, or forest and vegetation

type; or

(ii) State land, Tribal land, or private land;

(F)(i) a review of the national strategy described in the report entitled ‘‘The National Strategy: The Final Phase in the Development of the National Cohesive Wildland

Fire Management Strategy’’ and dated April 2014; and

(ii) any recommendations for changes to that national strategy to improve its effectiveness; and

(G)(i) an evaluation of coordination of response to, and suppression of, wildfires occurring on Federal, Tribal, State, and local land among Federal, Tribal, State, and local

agencies with jurisdiction over that land; and

(ii) any recommendations to improve the coordination described in clause (i).

Infrastructure Bill Forestry Provisions Summary: And Some Miscellaneous Goodies in 40804(b)

NAFSR (FS retirees organization) was kind enough to generate and post this summary of the Infrastructure Bill (passed, not to be confused with the Recon bill we have discussed earlier). So many items of interest to discuss! Let’s look at one big chunk of $ here, lots of diverse goodies we might not expect to find:

40804(b) the portion designated for the FS is directed to be spent as follows:

• (1) $150 million for FS to enter into landscape-scale contracts, including stewardship contracts, to

restore ecological health on federal land (over 10,000 acres per contract) and $100 million to DOI to

establish a Working Capital Fund that may be accessed by both DOI and USDA to fund requirements

of landscape-scale contracts, including cancellation and termination costs, consistent with section

604(h) of HFRA and periodic payments over the span of the contract period

• (2) $160 million for FS to provide funds to States and Tribes for implementing restoration projects on

federal land through the Good Neighbor Authority

• (3) $400 million for USDA to provide financial assistance to facilities that purchase and process

byproducts from ecosystem restoration projects, based on a ranking of the need to remove the

vegetation and whether the presence of a new or existing wood product facility would substantially

reduce the cost of removing the material. Also encourages the spending of other federal funds based

on the ranking criteria for removal of vegetation and presence of a wood processing facility or forest

worker is seeking to conduct restoration treatment work on or in close proximity to the unit.

• (5) $50 million for FS to award grants to States and Tribes to establish rental programs for portable

skidder bridges to minimize stream bed disturbance on non-Federal land and Federal land.

• (6) $100 million for FS to detect, prevent, and eradicate invasive species at points of entry and grants

for eradication of invasive species on non-federal land and on federal land

• (7) $100 million (split between DOI and FS) shall be made available to restore, prepare, or adapt

recreation sites on Federal land, including Indian forest land or rangeland with (as described in

40804(e)):

o $35 million shall be made available to FS to restore, prepare, or adapt recreation sites on Federal

land, including Indian forest land or rangeland, that have experienced or may likely experience

visitation and use beyond the carrying capacity of the sites.

o $20 million shall be made available to FS for the operation, repair, reconstruction, and

construction of public use recreation cabins on National Forest System land; and the repair or

reconstruction of historic buildings that are to be outleased under section 306121 of title 54,

United States Code. Of the 20 million, $5 million shall be made available to the Secretary of

Agriculture for associated salaries and expenses in carrying out that subparagraph.

o A project shall not be eligible for funding under this subsection if funding for the project would

be used for deferred maintenance, as defined by Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board;

and the DOI or USDA has identified the project for funding from the National Parks and Public

Land Legacy Restoration Fund.

• (8) $100 million to FS to restore native vegetation and mitigate environmental hazards on federal and

non-federal previously mined land.

• (9) $130 million for FS to establish and implement a national revegetation effort on Federal and nonFederal land.

• (10) $80 million to FS establish a collaborative-based, landscape scale restoration program to restore

water quality or fish passage on Federal land, in coordination with DOI. Section 8004(f) includes

language establishing this competitive program for five-year proposals of not more than $5 million

each. Gives priority to a project proposal that would result in the most miles of streams restored for

the lowest amount of Federal funding.

**************

Lots of goodies here for everyone… I thought the $400 mill for financial assistance to groups that “purchase and process byproducts” was interesting; so far that has seemed like a place where financial nudges could help restoration efforts along.

Tomorrow.. the NEPA-related provisions.

Big Bucks for the Forest Service (and Interior) in the Infrastructure Bill Passed Friday: I Wildfire Risk Reduction.

Somewhere someone has analyzed this bill.. would appreciate links, because I’m sure I am missing a great deal. Or if you notice something interesting I missed, please put in in comments. Bill Gabbert of Wildfire Today has done a nice summary here and gives attention to the wildland firefighter changes. There’s a lot in this bill about the Forest Service, so this is the first of possibly many posts. Here’s a link to the bill.

Note that usually the USDA gets half the total bucks for each effort. Which makes me wonder whether the Departments will get together to implement some of these efforts, and which ones.

USDA

$50 mill is for preplanning (specifically including PODs) but also training in other areas. with $250 mill for implementing PODs.

$250 mill for prescribed fires.

$100 mill for collaboratives plus five years of funding of old CFLRPs plus some new CFLRPs.

$400 mill for

(i) conducting mechanical thinning and timber harvesting

in an ecologically appropriate manner that

maximizes the retention of large trees, as appropriate

for the forest type, to the extent that the trees promote

fire-resilient stands; or

(ii) precommercial thinning in young growth stands

for wildlife habitat benefits to provide subsistence

resources; and

$100 mill for locally- based organizations’ laborers to modify remove and use flammable vegetation.

$100 mill for post-fire restoration in first three years.

$20 mill for Joint Fire Science Program (research).

I note that in 180 days the FS needs to publish an updated communities at risk map. This bill uses the HFRA definition of WUI.

************************

SEC. 40803. WILDFIRE RISK REDUCTION.

(a) AUTHORIZATION OF APPROPRIATIONS.—There is authorized

to be appropriated to the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary

of Agriculture, acting through the Chief of the Forest Service,

for the activities described in subsection (c), $3,369,200,000 for

the period of fiscal years 2022 through 2026.

(b) TREATMENT.—Of the Federal land or Indian forest land

or rangeland that has been identified as having a very high wildfire

hazard potential, the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary

of Agriculture, acting through the Chief of the Forest Service,

shall, by not later than September 30, 2027, conduct restoration

treatments and improve the Fire Regime Condition Class of

10,000,000 acres that are located in—

(1) the wildland-urban interface; or

(2) a public drinking water source area.

(c) ACTIVITIES.—Of the amounts made available under subsection

(a) for the period of fiscal years 2022 through 2026—

(1) $20,000,000 shall be made available for entering into

an agreement with the Administrator of the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration to establish and operate a

program that makes use of the Geostationary Operational

Environmental Satellite Program to rapidly detect and report

wildfire starts in all areas in which the Secretary of the Interior

or the Secretary of Agriculture has financial responsibility for

wildland fire protection and prevention, of which—

(A) $10,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(B) $10,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture;

(2) $600,000,000 shall be made available for the salaries

and expenses of Federal wildland firefighters in accordance

with subsection (d), of which—

(A) $120,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(B) $480,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture;

(3) $10,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior to acquire technology and infrastructure for

each Type I and Type II incident management team to maintain

interoperability with respect to the radio frequencies used by

any responding agency;

(4) $30,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture to provide financial assistance to States, Indian

Tribes, and units of local government to establish and operate

Reverse-911 telecommunication systems;

(5) $50,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior to establish and implement a pilot program

to provide to local governments financial assistance for the

acquisition of slip-on tanker units to establish fleets of vehicles

that can be quickly converted to be operated as fire engines;

(6) $1,200,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture, in coordination with the Secretary of the

Interior, to develop and publish, not later than 180 days after

the date of enactment of this Act, and every 5 years thereafter,

a map depicting at-risk communities (as defined in section

101 of the Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 (16 U.S.C.

6511)), including Tribal at-risk communities;

(7) $100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture—

(A) for—

(i) preplanning fire response workshops that

develop—

(I) potential operational delineations; and

(II) select potential control locations; and

(ii) workforce training for staff, non-Federal firefighters,

and Native village fire crews for—

(I) wildland firefighting; and

(II) increasing the pace and scale of vegetation

treatments, including training on how to prepare

and implement large landscape treatments; and

(B) of which—

(i) $50,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(ii) $50,000,000 shall be made available to the

Secretary of Agriculture;

(8) $20,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture to enter into an agreement with a Southwest

Ecological Restoration Institute established under the Southwest

Forest Health and Wildfire Prevention Act of 2004 (16

U.S.C. 6701 et seq.)—

(A) to compile and display existing data, including

geographic data, for hazardous fuel reduction or wildfire

prevention treatments undertaken by the Secretary of the

Interior or the Secretary of Agriculture, including treatments

undertaken with funding provided under this title;

(B) to compile and display existing data, including

geographic data, for large wildfires, as defined by the

National Wildfire Coordinating Group, that occur in the

United States;

(C) to facilitate coordination and use of existing and

future interagency fuel treatment data, including

geographic data, for the purposes of—

(i) assessing and planning cross-boundary fuel

treatments; and

(ii) monitoring the effects of treatments on wildfire

outcomes and ecosystem restoration services, using the

data compiled under subparagraphs (A) and (B);

(D) to publish a report every 5 years showing the

extent to which treatments described in subparagraph (A)

and previous wildfires affect the boundaries of wildfires,

categorized by—

(i) Federal land management agency;

(ii) region of the United States; and

(iii) treatment type; and

(E) to carry out other related activities of a Southwest

Ecological Restoration Institute, as authorized by the

Southwest Forest Health and Wildfire Prevention Act of

2004 (16 U.S.C. 6701 et seq.);

(9) $20,000,000 shall be available for activities conducted

under the Joint Fire Science Program, of which—

(A) $10,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(B) $10,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture;

(10) $100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture for collaboration and collaboration-based activities,

including facilitation, certification of collaboratives, and

planning and implementing projects under the Collaborative

Forest Landscape Restoration Program established under section

4003 of the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of

2009 (16 U.S.C. 7303) in accordance with subsection (e);

(11) $500,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture—

(A) for—

(i) conducting mechanical thinning and timber harvesting

in an ecologically appropriate manner that

maximizes the retention of large trees, as appropriate

for the forest type, to the extent that the trees promote

fire-resilient stands; or

(ii) precommercial thinning in young growth stands

for wildlife habitat benefits to provide subsistence

resources; and

(B) of which—

(i) $100,000,000 shall be made available to the

Secretary of the Interior; and

(ii) $400,000,000 shall be made available to the

Secretary of Agriculture;

(12) $500,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture, in cooperation with States, to award community

wildfire defense grants to at-risk communities in accordance

with subsection (f);

(13) $500,000,000 shall be made available for planning

and conducting prescribed fires and related activities, of

which—

(A) $250,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(B) $250,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture;

(14) $500,000,000 shall be made available for developing

or improving potential control locations, in accordance with

paragraph (7)(A)(i)(II), including installing fuelbreaks

(including fuelbreaks studied under subsection (i)), with a focus

on shaded fuelbreaks when ecologically appropriate, of which—

(A) $250,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(B) $250,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture;

(15) $200,000,000 shall be made available for contracting

or employing crews of laborers to modify and remove flammable

vegetation on Federal land and for using materials from treatments,

to the extent practicable, to produce biochar and other

innovative wood products, including through the use of existing

locally based organizations that engage young adults, Native

youth, and veterans in service projects, such as youth and

conservation corps, of which—

(A) $100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(B) $100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture;

(16) $200,000,000 shall be made available for post-fire restoration

activities that are implemented not later than 3 years

after the date that a wildland fire is contained, of which—

(A) $100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of the Interior; and

(B) $100,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture;

(17) $8,000,000 shall be made available to the Secretary

of Agriculture—

(A) to provide feedstock to firewood banks; and

(B) to provide financial assistance for the operation

of firewood banks; an

Sec. 40801 Legacy Roads and Trails

When I was doing the review of environmental groups’ views, this is one of the rare programs that everyone from AFRC to WEG supported. Lots of specifics I’m not posting. We’ve been discussing transportation planning and I thought that this was an interesting take:

‘‘(d) IMPLEMENTATION.—In implementing the Program, the Secretary

shall ensure that—

‘‘(1) the system of roads and trails on the applicable unit

of the National Forest System—

‘‘(A) is adequate to meet any increasing demands for

timber, recreation, and other uses;

‘‘(B) provides for intensive use, protection, development,

and management of the land under principles of

multiple use and sustained yield of products and services;

‘‘(C) does not damage, degrade, or impair adjacent

resources, including aquatic and wildlife resources, to the

extent practicable;

‘‘(D) reflects long-term funding expectations; and

‘‘(E) is adequate for supporting emergency operations,

such as evacuation routes during wildfires, floods, and

other natural disasters; and

‘‘(2) all projects funded under the Program are consistent

with any applicable forest plan or travel management plan.

*************

AUTHORIZATION OF APPROPRIATIONS.—There is authorized

to be appropriated to the Secretary of Agriculture to carry out

section 8 of Public Law 88–657 (commonly known as the ‘‘Forest

Roads and Trails Act’’) $250,000,000 for the period of fiscal years

2022 through 2026.

Out of the Ashes: Landscape Recovery in the Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region

This is a very interesting, eye-catching, and technologically splendid (IMHO) presentation by Region 5 on what they are doing post-fire. As an old person who worked at Placerville Nursery during its heyday (at a genetics lab then located in the seed extractory, to be specific) I’m not surprised to see that the spiral of learning has circled back to the need to plant trees. This spiral tends to recur almost predictably when everyone with expensively obtained experience has retired, and the infrastructure dispersed (remember Region 6 tree coolers?). And so it goes..

There’s many possible discussion topics but these caught my eye..

Critical Reforestation Needs

Over half the landscape burned at moderate to high severity.

500,000 acres prioritized for reforestation.

Estimated cost of 2020 of revegetation/site prep is over $585M.

Strategic Reforestation Investment

Long term reforestation strategy.

Modernizing our nursery.

Adapting tree species and revegetation to climate change.

~$2M Placerville CIP request.

$3.5M in grants, proposals and match.Wildfires necessitate long-term repairs to trails, roads & streams.

Trail restoration – 1,600 mi

Estimated costs $9M

Road restoration & bridge reconstruction – 5,894 mi

Estimated costs $874M

Approved ERFO $10M

Watershed Restoration & improvement – 8,600 miles

Estimated costs $138M

Facility ReplacementAdditional infrastructure recovery accounts for admin sites, recreation facilities, and bridges.

Estimated costs administrative sites – $15M

Estimated costs recreation sites – $19M

Estimated costs infrastructure design & contract admin – $298M

Strength Through PartnershipTrillion Trees & Expansion of Placerville Nursery.

CalTrans agreement for roadside salvage.

Matching dollars from NFWF, CAL FIRE, BLM.

State proposing $2B for wildfire and forest resilience.

And where there is fire and trees (and markets), there is salvage (both public and private, although private does not seem to be controversial).

Burned Timber

Burned timber from 2020 wildfires – 20x more than R5’s timber target.

Not all can be salvaged due to access and terrain

Mill & biomass facility capacity is limited and variable

Potential for saturated salvage market

Carbon in the AtmosphereMore than 112M metric tons of CO2 were emitted into the atmosphere due to 2020 wildfires.

25% more CO2 than the average annual fossil fuel emissions.

*********************

I wonder whether both Oregon and California have the potential for a saturated salvage market, who will get in before saturation, and what will happen to the rest of the material. How the FS will determine priorities beyond hazard trees? What will happen to all the material that is removed but doesn’t find a market?

Anyway, great job, Region 5!