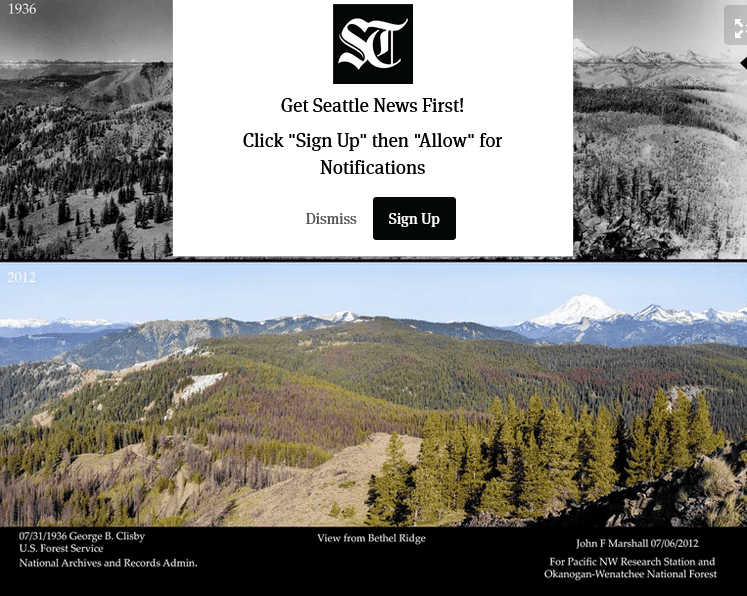

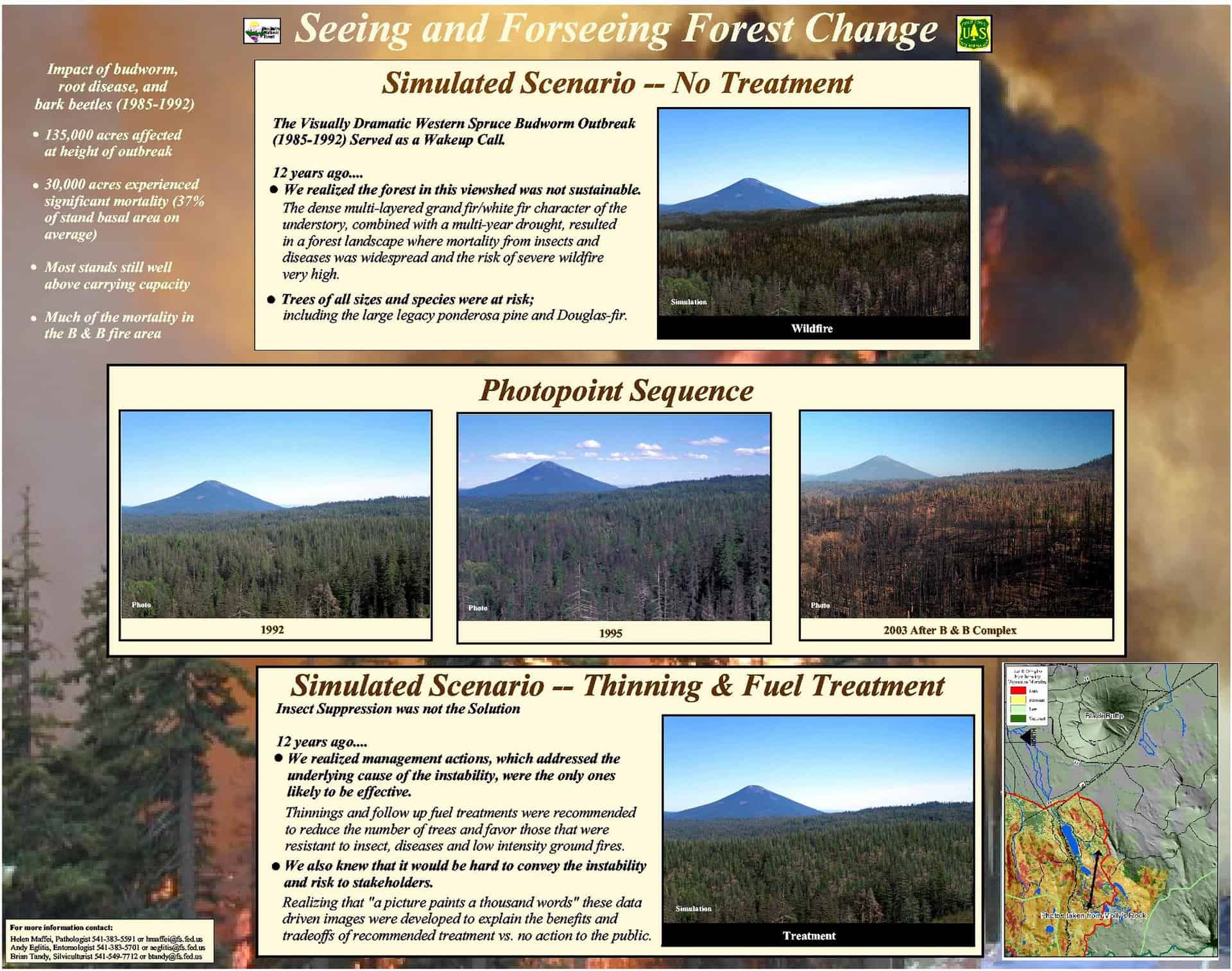

The above photo is from 2007, by R6 State and Private Forestry of western spruce budworm defoliation. It wasn’t identified to location as far as I could see.

This one is on the Deschutes. For those interested, there is an extensive historical record of photos about various spruce budworm projects here. If you worked on any of those projects you might find a photo of yourself!

This one is on the Deschutes. For those interested, there is an extensive historical record of photos about various spruce budworm projects here. If you worked on any of those projects you might find a photo of yourself!

******************

I think we’re having a great discussion about the East-Side screens and the 21- inch diameter rule. Here I’d like to throw in an Old Person observation from my time on the Ochoco during the 80’s. It’s an Old Person observation about what seems to have changed and what has not changed in 40 years. I worked for four forests (the Fremont, Winema, Ochoco and Deschutes), but I’ll focus on the Ochoco.

**************

Historical aside: The Ochoco Supervisor’s Office at the time was a large open, cubicle puzzle space. I sat in the silviculture zone, next to the irrepressible Duane Ecker, the forest silviculturist, Don Wood and our boss, the Timber Staff, Chuck Downen. But thanks to the wonders of the cubicle environment, I often heard conversations of the Law Enforcement Officer (finding that particularly interesting things were said when he lowered his voice.. “the perpetrator…”). We all had Data Generals (DG’s). Unfortunately, but sometimes entertainingly, our Public Affairs Officer, Joe Meade (who was visually impaired), had a DG that read his email out loud .. in a tinny.. monotonous.. slow… voice. Apparently headphones were too technically or financially difficult to procure.

**********

At the time, people were running Forplan, and somehow we were involved in the tree-growing part. It could have been John Cissel, our Forplan soothsayer or Bill Anthony, his Deschutes counterpart , who told us “Forplan tells us to cut the ponderosa pine and grow grand fir, because they grow faster and ultimately produce more volume.” Or something like that. I know there are folks here who know more about what Forplan was supposed to be doing than I do.

So we silviculture folks explained why we thought that that was not a good idea. White fir/grand fir/ hybrid (WGH) firs aren’t fire resistant. They have a tendency to get spruce budworm, Doug-fir tussock moth, fir engraver, and a variety of root and other diseases.

So flash forward to today.. now “growing faster” is good idea-wise due to carbon.In this story about a study that Anonymous referred to:

“This is why specifically letting large trees grow larger is so important for climate change because it maintains the carbon stores in the trees and accumulates more carbon out of the atmosphere at a very low cost.”

The study highlights the importance of protecting existing large trees and strengthening the 21-inch rule so that additional carbon is accumulated as 21-30″ diameter trees are allowed to continue to grow to their ecological potential.

As a former silviculture worker, this feels pretty much the same as the Forplan idea of 40 years ago. Assume- no fires, bugs, diseases, drought (conceivably made worse by climate change) and the firs will do fine by themselves! No openings for establishment of PP or WL necessary.

But silviculturists, forest pathologists and entomologists, and fuels practitioners are dealing with the same biophysical realities- that trees don’t grow- whether to be cut as in Forplan, or to sequester carbon- if they’re dead and /or burned. It’s interesting to see that the body of resource professionals’ knowledge haven’t changed much over time (the interaction of trees, bugs, diseases and fire), while ideas about what practitioners should be doing from Forplan to carbon..seem to come from, and have the imprimatur of, people (however well-meaning) generally from elsewhere; places, apparently where fire, bugs, diseases and drought are not a big thing.

***********************

If you want to see how much people already knew in 1994, there’s an excellent round-up, at least as far as the Blue Mountains go, by by the Malheur Forest Silviculturist, David C. Powell, in 1994- 30 years ago now. Same old..

White fir, the favorite food of spruce budworm, has flourished in the fir stands that have encroached on ponderosa pine sites over the last 80 years. By controlling natural underburns, land managers were inadvertently swapping ponderosa pines and western larches for white firs and Douglas-firs. (p. 5)

Ponderosa pine depends on fire to clear away accumulations of needles and twigs so its seeds can find moist mineral soil, and to kill encroaching firs that prevent seedlings from getting

the unobstructed sunlight they need.By controlling natural underburns, land managers allowed fire-resistant pines and larches to be replaced with shade-tolerant, late-successional species. Many of the replacement species are susceptible to the effects of western spruce budworm, Douglas-fir tussock moth, Indian paint fungus, Armillaria root disease, and other insects and pathogens. (p. 19)

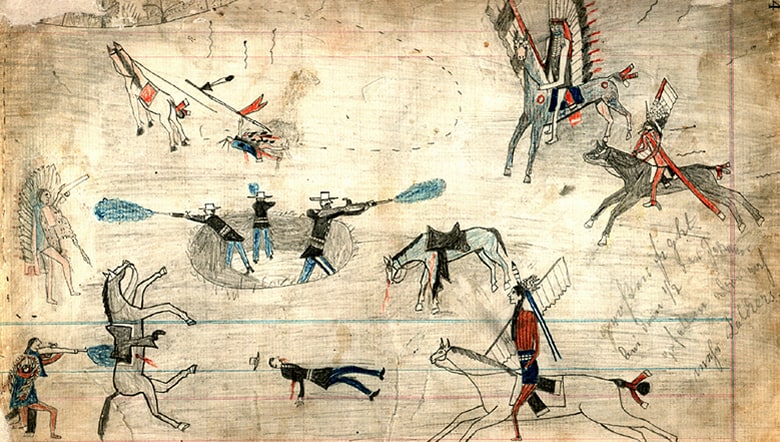

And there’s an interesting section on Native American burning practices:

Although some of the underburns were started by lightning storms in mid or late summer (Plummer 1912), many others were ignited by native Americans (Cooper 1961, Johnston 1970, Robbins and Wolf 1994). When analyzing early journals from the western U.S., Gruell (1985) found that over 40 percent of the fires were described as being started by native Americans.

Two major factors led to conversion of pine stands with underburning to laddered stands with shade-tolerant species. One was fire suppression:

Many land managers would agree that wildfire suppression was a policy with good intentions, but it was a policy that failed to consider the ecological implications of a major shift in species composition. White firs and Douglas-firs can get established under ponderosa pines in the absence of underburning, but they may not have enough resiliency to make it over the long run, let alone survive the next drought. This means that many of the mixed-conifer stands that have replaced ponderosa pine are destined to become weak, and weak forests are susceptible to insect and disease outbreaks (Hessburg and others 1994).

By controlling natural underburns, land managers allowed fire-resistant pines and larches to be replaced with shade-tolerant, late-successional species. Many of the replacement species are susceptible to the effects of western spruce budworm, Douglas-fir tussock moth, Indian paint fungus, Armillaria root disease, and other insects and pathogens. (p. 19)

The other reason was the attraction of cutting pine and leaving the GWH firs. Powell provides some detailed explanations of why that seemed like a good idea at the time (mo clearcutting, no expensive tree planting)(p. 27) . And there were interactions between controlling underburns and reducing tree vigor due to competition, so then they would want to take these stressed pines.

Since old pines often have low vigor and little resistance to insect attack, they were harvested before being attacked and killed by western pine beetle or mountain pine beetle. One reason for low vigor in oldgrowth pine trees was competition from a dense understory, an understory that would not have been present if underburning had been allowed to play its natural role.

In 1994 folks were thinking about climate change:

Reestablishing ponderosa pine and western larch on sites that are suitable for their survival and growth, and a thinning or prescribed fire program to keep those stands open and vigorous, would probably do much to address global warming concerns. Using a plan like that one would not only restore much of the pine and larch that was removed by partial cutting (see fig. 21), but it could also create healthy forests with an increased resistance to a variety of insects and pathogens.

And they were also thinking about (healthy=preEuro times) (p. 34)

Perhaps an appropriate yardstick of ecosystem health is natural variation: are the changes caused by budworm consistent with the historical range of variation for similar ecosystems and vegetation conditions? For the mixed conifer forests of the southern Blue Mountains, the answer is probably “no.” It seems that 80 years of fire suppression and 50 years of selective harvesting have resulted in vegetation conditions that differ significantly from those of presettlement times (Table 3).

***********

If some think that the FS wants to cut larger GWH fir unnecessarily, why would they want to do that?

Foster (1907) White fir, though occasionally used for fuel when no better species are available, makes poor fuel wood, while for saw timber it is all but valueless owing to the fact that nearly all mature trees are badly rotted by a prevalent polyporus, and the wood season-checks badly. (p.30)

Forest Service employees have sometimes been called p— firs due to the “badly rotted” characteristics of white fir.