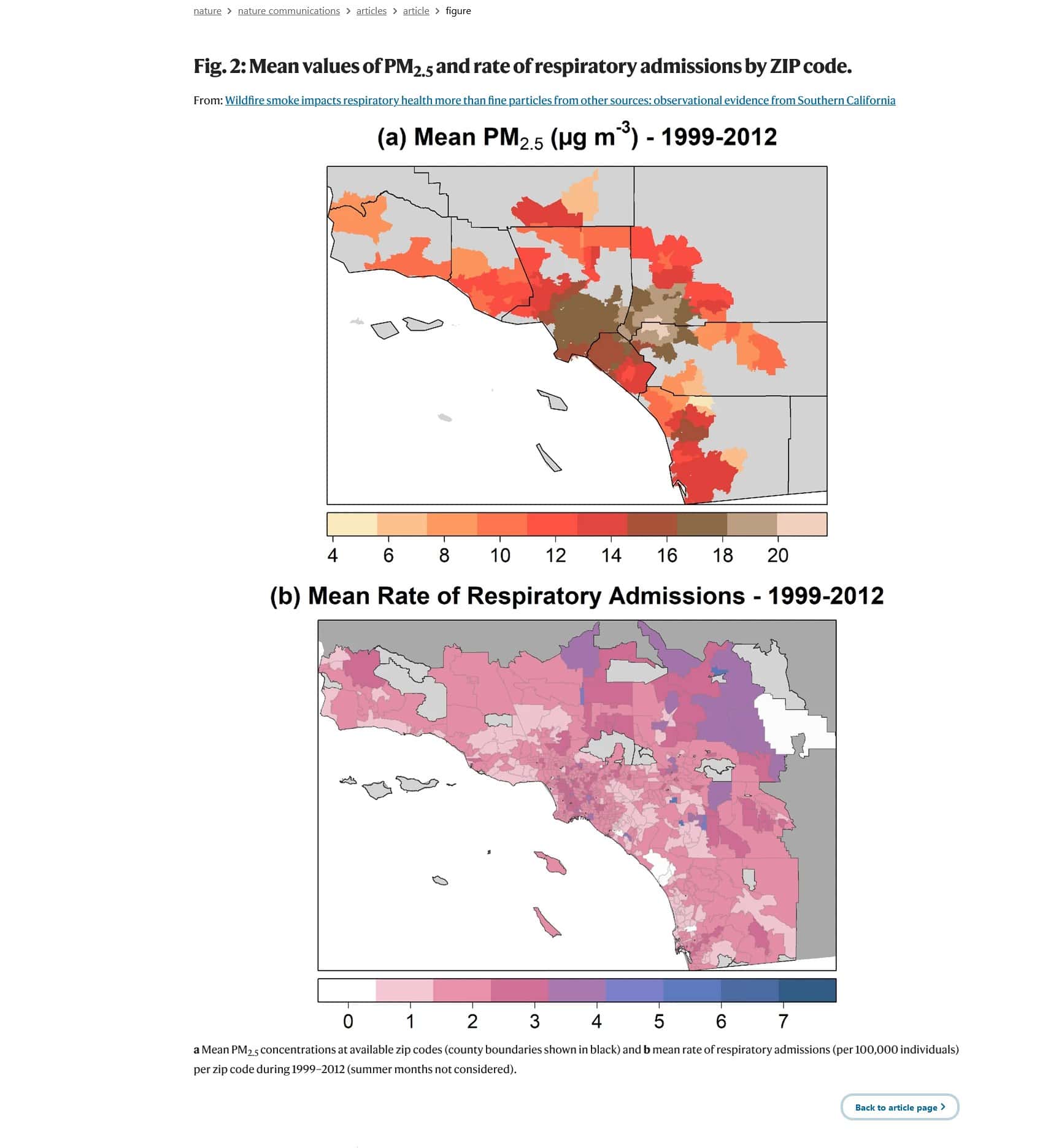

The WaPo had an interesting article last week on PM2.5 regulations. I wouldn’t be following this if it weren’t for the wildfire/prescribed fire angle on PM 2.5. There seems to be a discussion that since wildfires and prescribed burning emit particulates, that therefore industrial sources should reduce even more. Then there are studies that say different PM2.5 sources can have different health effects, with wildfire particulates being more harmful. From that study:

PM2.5 in the United States has decreased in past decades due to environmental regulations5,8, with the exception of wildfire-prone areas5. Wildfire PM2.5 in the US is projected to increase with climate change along with the associated burden on human health9. Levels of wildfire PM2.5 can greatly exceed those of ambient PM2.5, spiking episodically within a short period of time (e.g., hours after the onset of a wildfire),

It also seems to me that wildfire and prescribed fire are different than industrial, as exposure is more due to kinds of work than to where a person lives. It is true that industries tend to be in poorer areas. But maybe the solution is to focus on those industries, rather than a broad brush across all sources. Note how quickly the world as we might see it, complex and full of different particles and different effects, becomes framed as good guys versus bad guys. And the paradox that “bad guy” industries also provide living-wage jobs for lower-income people can be transformed into a crude political calculus. This may give EPA even more authority over wildfire and prescribed fire than it has with fire retardant permitting. In fact, wildfire and prescribed fire may become wholly owned subsidiaries of EPA decisionmakers. As would all areas transferred, by a stroke of the regulation pen, into non-attainment. I see this quite a bit, what we might think are complex issues are reframed as simple (the less PM 2.5 the better, regardless of other needs and concerns) and then translated into good guys and bad guys.

So look how the reporter frames the issue:

The Environmental Protection Agency is preparing to significantly strengthen limits on fine particle matter, one of the nation’s most widespread deadly air pollutants, even as industry groups warn that the standard could erase manufacturing jobs across the country.

So it’s industry folks (bad) vs. the EPA (good):

Public health advocates strongly disagree with the industry’s assertions. They say strengthening the soot standard would yield significant medical and economic benefits by preventing thousands of hospitalizations, lost workdays and lost lives, particularly in communities of color that are disproportionately exposed to unhealthy air.

********

EPA lawyers have said in court filings that the soot rule could be finalized by the end of this month. As soon as next week, the agencyis expected to lower the annual soot standard to 9 micrograms per cubic meter of air, down from the current standard of 12 micrograms, according to two people briefed on the matter who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to comment publicly.

*******

We are reassured by EPA that there are no trade-offs. Maybe EPA needs more economists? As Thomas Sowell said, “there are no solutions, only trade-offs.” Anyway, our own forest folks show up in this article.

A limit of 9 micrograms could sharply increase the number of counties that are in violation of the soot standard or just below the threshold, according to a map produced by the American Forest & Paper Association, a trade group. Companies would then have a harder time getting permits to build or expand their industrial plants, potentially prompting them to move to other countries with weaker environmental rules, the group says.

“Our average ambient level of PM2.5 in this country is 8; in China and India, it’s about 5 to 6 times that level,” said Heidi Brock, the American Forest & Paper Association’s president and chief executive. “What sense does it make to offshore jobs from this country, where we have some of the cleanest air on the planet?”

So the Post analyzes it from a political point of view… is this the time to stop building manufacturing in the red areas?

“Detroit is red. Philadelphia is red,” he added. “Why would the White House effectively redline new manufacturing facilities in urban Democratic strongholds where young workers need high-paying, frequently unionized manufacturing jobs?”

****************

“Lowering the standard to 8 micrograms per cubic meter, in terms of long-term exposure, would benefit vulnerable communities the most,” said Francesca Dominici, a professor of biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a co-author of the study.

Research has also found that wildfire smoke, a major nonindustrial source of soot, has slowed or reversed air quality improvements in much of the country. Industry groups have seized on these findings to argue that their soot emissions are a small part of the problem. But public health experts counter that wildfires are exacerbated by climate change, which in turn is exacerbated by industrial pollution.

“We know that these wildfires are getting worse and more intense due to climate change,” said Marianthi-Anna Kioumourtzoglou, an associate professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health. “And it’s the same industries that emit PM2.5 that also emit a lot of the greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.”

It’s great to be against industrial pollution. It’s great to be in public health. But this is kind of a weird conflation (and the expert neither an expert in climate nor wildfires) kind of statement, unless the point is to export 2.5-emitting manufacturing to countries likely to be poorer (with lower wages) where they would be emitting the same or more greenhouse gases.