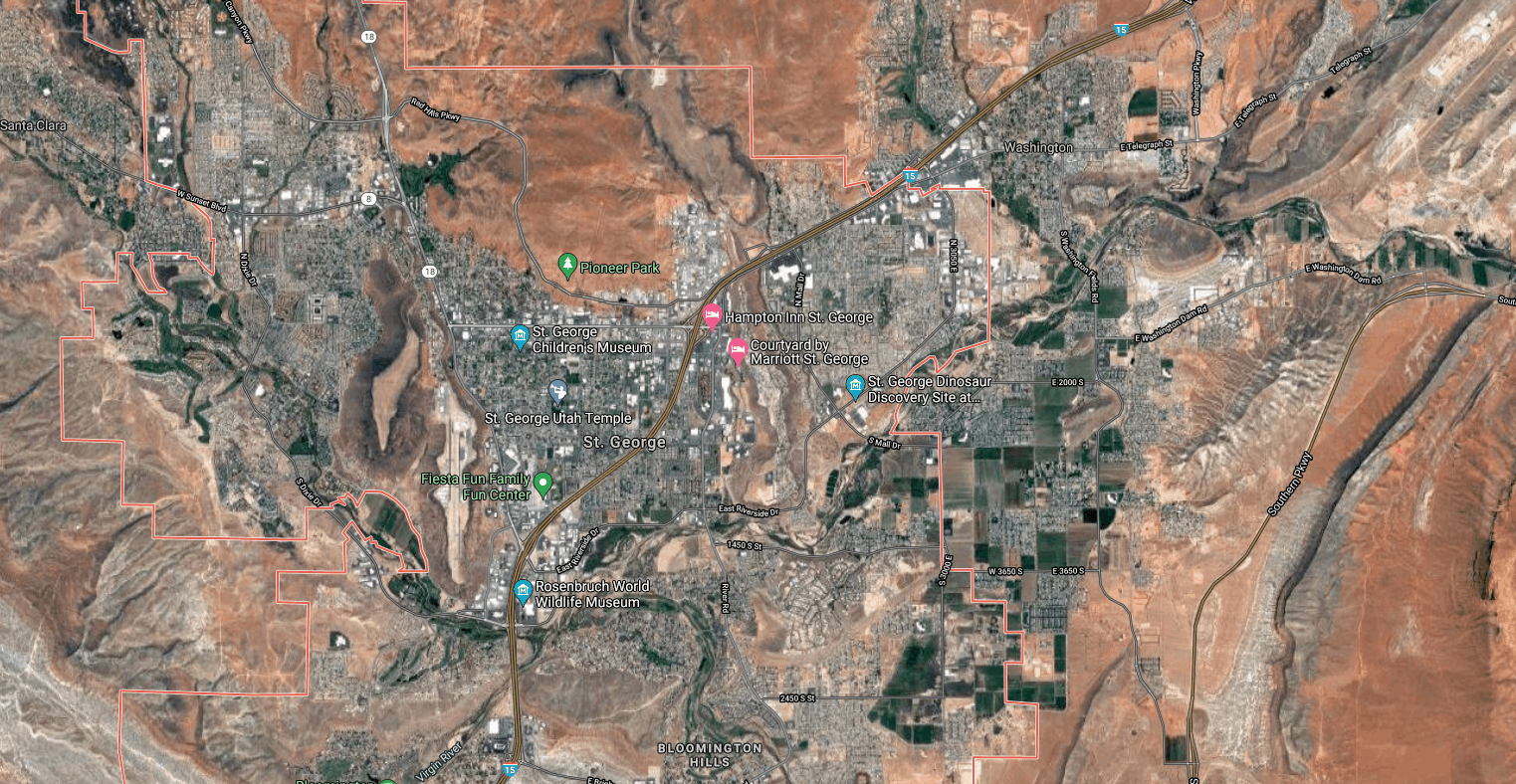

I just returned from a driving trip from Colorado to Los Angeles California, and to Sacramento, California, passing through New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and Utah, including passing through one of my favorite highways, US 50 in Nevada, “the loneliest road in America”. Shout out to the BLM and the Humboldt-Toiyabe NF! In many places, NPR was the only station I could get (in rental car, because my 252K car was receiving a well-earned rest). It was fascinating to listen to NPR’s ideas of what was happening in “the West” and relate them to my own observations. It’s interesting to check every story you read about “the West” and wonder “do they mean Malibu, Eugene, Baker, Fallon, Red Feather Lakes, Chugwater, Silver City, Raton, Helena, Wenatchee, Republic or…?”Well, you don’t have to think very far to think “those places are incredibly different.. historically, which Tribes, which folks settled, which folks are there now, where folks are moving to these areas from, and so on.” And money, of course, is a thing.

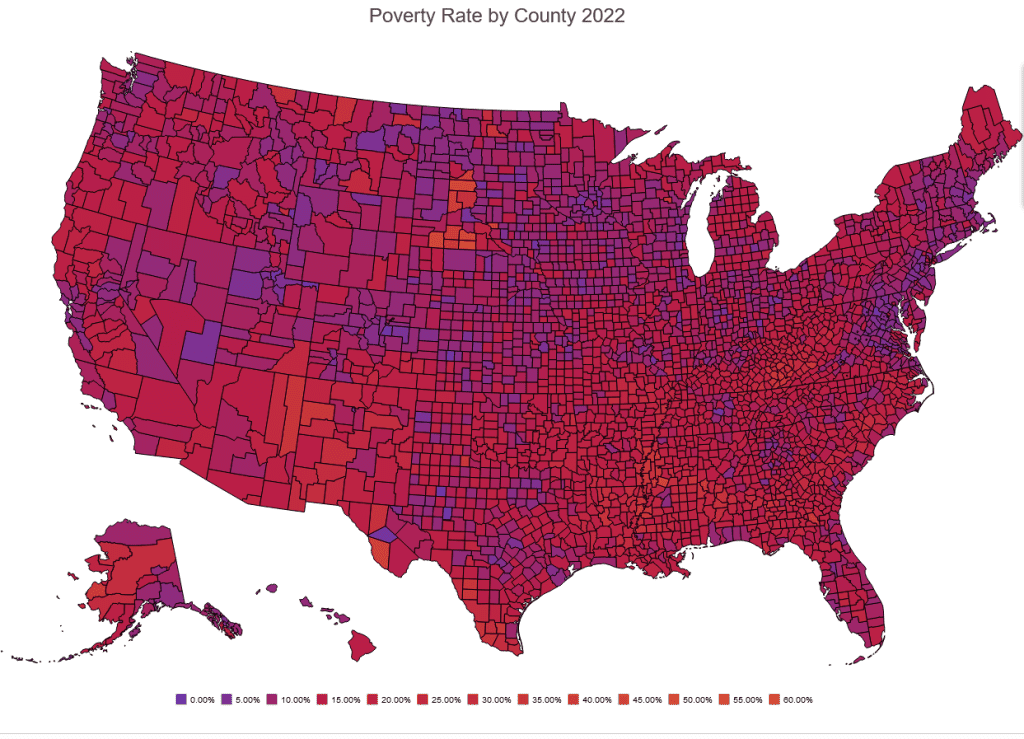

Counties in the “West” range from among the richest in the country (say around the SF Bay area) to some of the poorest. It’s an amazing diversity of peoples and cultures.

A year or two ago, I was on a Zoom session with folks from the Society of Environmental Journalists on people covering “western” federal lands issues. Most of the folks were not from what I’d call the Interior West, that would be from the crest of the Cascades/Sierra/Angeles to the Great Plains. They were (to me) surprisingly focused on “we need to cover people in “the West” who are planning to overthrow the government” (this was after January 6). I’m not kidding, of all our issues, really? Of all the issues we (I’ll call us Interior Westerners) face, these folks seem to believe that we in the IW are infested with incipient Bundys. And what surprised me the most is that these people seemed to really believe it and thought it was important to impart this (misplaced, IMHO) fear to the rest of the world. Of all the local papers I’ve read over the years, I haven’t seen many other Bundys.. but why the Bundobsession?

Many thanks to Matthew for posting the High Country News piece that illustrates my point. From Mr. Segerstrom (who resides in Spokane, definitely the Interior West):

THE WESTERN U.S. isn’t the only place where anti-government sentiment festers, but here the wounds are open, frequently endured and historically recent. Violence and the threat of violence in the region occur within the context of a nation founded on the genocide of Indigenous people. Leaders of anti-federal movements lean into this violent history and include factions that are specifically anti-Indigenous. In defending his right to graze cattle on federal land in Nevada — a claim he successfully defended at Bunkerville in 2014, when federal authorities withdrew after being outgunned by militiamen — Bundy argued that his claim to the land was more legitimate than the Southern Paiutes’ because “they lost the war.”

This white-plus-might-makes-right sentiment is a pervasive feature of Western mythology and cowboy culture. Over the last half-century, anti-government leaders have rallied to that image as the West’s population swelled and control over its natural resources became more contested and regulated. The original Sagebrush Rebellion of the mid-to-late-1970s — which inspired the modern Bundy-led standoffs but were not nearly as paramilitary — came in response to federal public-land laws like the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, Wilderness Act and Endangered Species Act, which increasingly restricted how natural resources could be used.

Those restrictions were seen as unconscionable overreach by rural Westerners who were accustomed to using public-land resources as they wished. “The hardest thing to do in American politics is to withdraw a right,” said Daniel McCool, a political science professor at the University of Utah. Even though those rights were privileges in the legal sense, the perception that they were rights, and that they were being taken away, fueled the original Sagebrush Rebels, McCool said. “The roots of the Sagebrush Rebellion were when they no longer got what they wanted,” he said. “There’s a direct line from there to the Bundy groups active today.”

Hmm. So the East, South, and Midwest, weren’t founded on the “genocide of Indigenous people.” And, of course, as a native of Southern California, there are all kinds of racial complexities, as there colonization was accomplished by the Spanish. But today’s descendants of these folks are not considered exactly “white”(although I think some have been called “white-adjacent”. And cowboy culture has included diverse folks..this Smithsonian story says that one in four were black.

And originally cowboys (vaqueros) were of both Spanish and Native origin. Think of words like bronco and reata.

While classic Westerns have cemented the image of cowboys as white Americans, the first vaqueros were Indigenous Mexican men. “The missionaries were coming from this European tradition of horsemanship. They could ride well, they could corral cattle,” says Rangel. “So they started to train the native people in this area.” Native Mexicans also drew on their own experiences with horsemanship and hunting buffalo in order to refine vaquero techniques further, says Rangel.

In addition to herding cattle for Spanish ranchers as New Spain expanded westward, vaqueros were also enlisted as auxiliary forces in skirmishes between native communities and others.

This stereotype of “westerners” are always rural sometimes well-off, sometimes not (interesting to watch) people ( I don’t think they mean Cher or Steve Jobs), thought to be ignorant and violent.

Lest you think the Coastal Gaze is something new, I ran across this statement in a book written in 1891 by a Mr. W. L. Holloway.

“There are two classes of people who are always eager to get up an Indian war-the army and our frontiersman”. I quote from an editorial on the Indian question, which not long since appeared in the columns of one of the leading New York daily newspapers. That this statement was honestly made I do not doubt, but that instead of being true it could not have been further from the truth I will attempt to show. I assert, and all candid persons familiar with the subject will sustain the assertion, that of all classes of our population the army and the people living on the frontier entertain the greatest dread of an Indian war, and are willing to make the greatest sacrifices to avoid its horrors.”..

“As to the frontiersman, he has everything to lose, even to life, and nothing to gain by an Indian war. “His object is to procure a fat contract or a market for his produce” adds the journal from which the opening lines of this chapter are quoted?…First our frontier farmers, busily employed as they are in opening up their farms, never have any produce to dispose of, but consider themselves fortunate if they have sufficient for their personal wants. .. The supplies are purchased far from the frontiers, in the rich and thickly settled portions of the States, then shipped by rail and boat to the most available military post..”

So seeing (some rural) Westerners as the “bad guys” is nothing new. And writing op-eds about what people in the “rural West” should be doing from New York.

I find this all, and its longevity through time, somewhat puzzling. Especially since various places in the Interior West are increasingly full of people from elsewhere..who may find these stereotypes laughable. Oh, and there’s the LDS folks in Utah, for whom we should feel a great deal of compassion due to their history as a religious minority persecuted by the US Federal Government. Or not?

It sounds a bit like “othering”

On an individual level, othering plays a role in the formation of prejudices against people and groups. On a larger scale, it can also play a role in the dehumanization of entire groups of people which can then be exploited to drive changes in institutions, governments, and societies. It can lead to the persecution of marginalized groups, the denial of rights based on group identities, or even acts of violence against others.

So.. when a story talks about “the West” what part are they talking about? And what’s up with Bundobsessing, and why is it such a popular activity among some in the journalism community?

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com