There has been a great deal of migration to the Interior West as part of the response to Covid. An example from Wyoming is here. People are moving out of the Bay Area in California, either to other parts of California, or away from California entirely. There’s an interesting interview here on WBUR Boston on this. People want to move away due to commuting and expense, but also I think possibly they don’t want to live in densely built cities next to public transit.. and don’t have to, if jobs are remote.

I think of them as maybe generational or some other kind of dimension of the challenge, because we know how to build houses. We have the technology elevators for more dense urban areas. We know how to do lots of things, including transit. But for some reason, the political structure isn’t allowing us to do any of those things that basic planners, basic economists have figured out.

Maybe it’s time to ask people if they want to live in those kinds of places, and press “reset” on the current planning paradigm. Maybe rents and home prices would naturally decline if only the people who had to physically be at work were in cities.

The relevance of all this to the Forest Service is clearly mega-increases in recreation, and the need for management of recreation impacts. It also affects the ability of employees to purchase homes in some amenity communities (of course, this has long been the case for employees in places like Jackson, Wyoming).

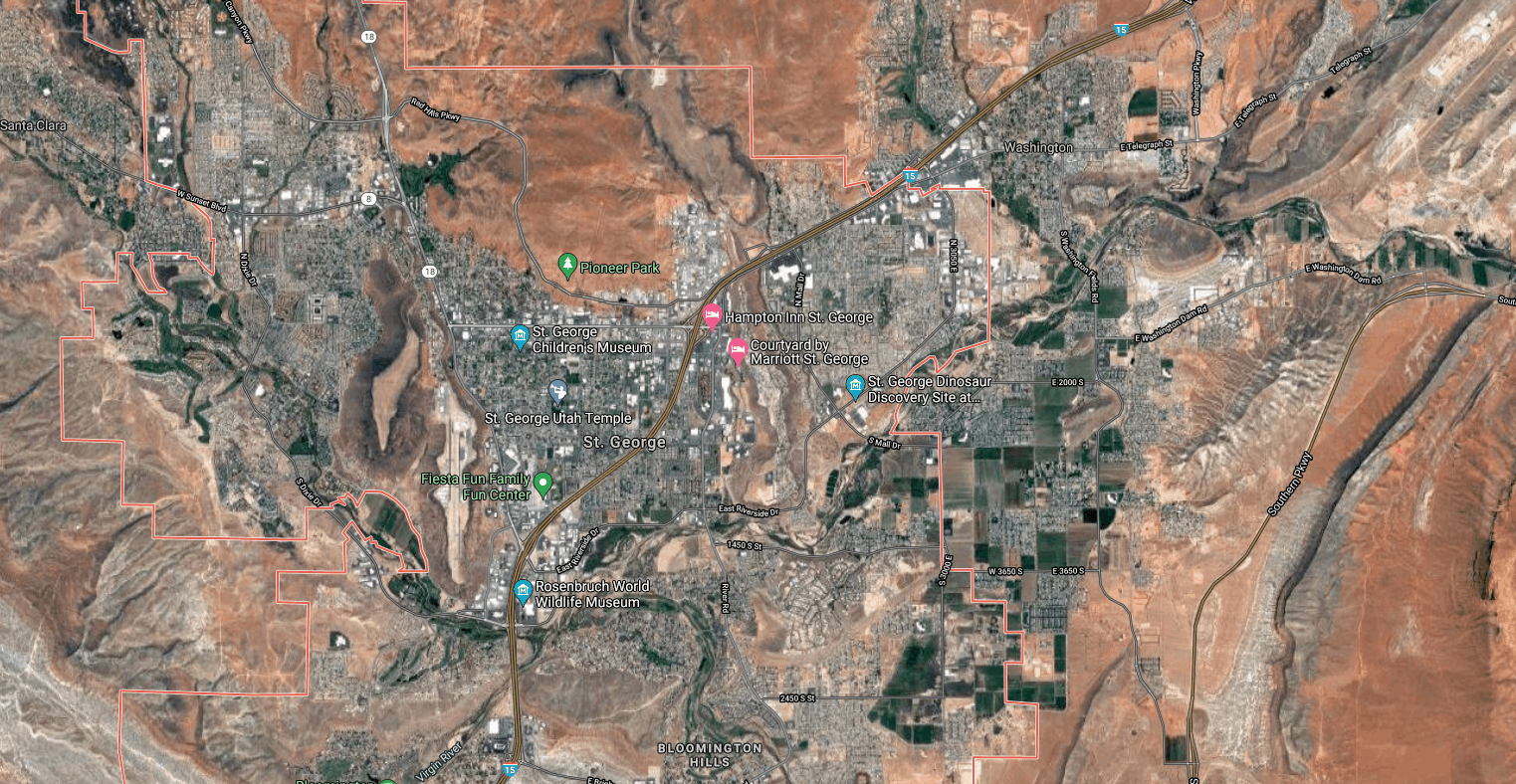

Having said all that, one of the most thoughtful pieces I’ve seen on this is by Stacy Young in the Canyon Country Zephyr in an article focusing on St. George, Utah. The article starts with a reference to pre-Covid and then looks at Covid-induced enhancement of those trends. Check the whole piece out, it’s a topic that isn’t written from the “moved to” places’ perspective all that often.

A year ago, I wrote about the development of the Little Valley area of St. George in southwest Utah. What I tried to do in that piece was use words, pictures and numbers to provide a specific example of what happens when good intentions and visionary land use plans are overwhelmed, as they usually are, by the dual pressures of industrial tourism and amenity in-migration, on the one side, and recalcitrant NIMBYism, on the other.

That piece was meant to be a case study pushing out on my running argument that the relatively recent phenomenon of permanent tourism is turning the ordinary, historical understanding of cities-as-labor-markets on its head. And to show, in effect, that it is almost certainly technocratic wishcasting to think that Good Planning will save a place from the cataclysmic money that is rushing into parts of Utah’s canyon country.

That essay was written in the Before Times and so it may be worth checking in to see what, if anything, has changed in the St. George area in the intervening year. What follows may also count as a partial reply to a comment left by reader Chris Patterson to that earlier piece:

What do people do for work in St George? I’m curious what all the new migrants do to pay for those 400k+ homes.

And what is the water source for this clearly water-intensive form of development?

And at what point will “amenity migration” stop because the amenities are ruined?

Thanks for an informative, and depressing, article. I wonder when this ideal of the over-large home on the plot of irrigated grass will finally just die out…

Many of us who have worked in Forest Service jobs have experienced this phenomenon directly and not just recently (remember Oregon’s efforts to encourage people not to move there? check out this Bill Moyers video from 1973 (yes, almost 50 years ago now). I like Young’s point #3. In our own states we all have examples of, say, Florence CO is not Aspen, it’s not even Meeker.

The existence of an “amenity” in a place is a necessary but insufficient condition for amenity migration. The capacity for move-ins to decouple their economic well-being from the local labor market is also imperative.

What constitutes an “amenity” is far more subjective than ordinarily presumed. The opportunity for capitalistic manufacture of amenities is nearly endless. But do not expect amenitization’s synthetic flexibility to be evenly or constructively employed. Count on this feature not to ameliorate social problems but to exacerbate them.

- “Amenity migration” is a nice, clean term that implies a more uniform phenomenon than exists in practice. There are certainly commonly observed features, but the differences matter and they are pronounced. One community may grow in more or less normalish ways. Another may not grow its permanent community at all and instead simply become an ever more exclusive enclave of dilettantes and consumers. Most places will fall outside either of these two extreme descriptions.

It is the epitome of technocratic arrogance to suppose that amenity migratory patterns will readily yield to planning or analysis. Human civilization is more like an organism than a machine; it is complex rather than merely complicated.

Coda. Californians*, having ruined their own primary housing markets, are no longer content to export just a bit of their dysfunction onto one rarified second-home destination or another, but instead appear set to entirely wreck any number of housing markets across Texas and the interior West. Let’s dissect the process, using figures from San Mateo County in the Bay Area to help illustrate.

Step one: Create a massive housing gap. “Between 2010 and 2019, 102,500 new jobs were created in San Mateo County, while only 9,494 new housing units were built, a 11:1 ratio.”

Step two: Wait patiently as the extreme imbalance between housing demand and its supply causes home values to become an exercise in absurdity. Between the mid-90s and now, the median home price in San Mateo County skyrocketed from the mid-$300,000s to about $1,700,000, a roughly 5-fold increase.

Step three: Engage in a little harmless arbitrage. Use the internet tools invented in and around San Mateo to remain attached to the Silicon Valley labor market while detaching from its dysfunctional housing market.

Step four: After selecting your Zoom Town of choice, cash out your home equity and reinvest all or most of it in your lucky new hometown. It’s almost like an early-stage investment in an exciting new startup!

Bonus step five: Charm new acquaintances by expressing shocked delight at what a nice house $1 million gets you.

Bonus step six: Continue your old home voter ways in your new hometown by furiously and without a trace of irony lobbying your local elected officials to clamp down on housing production lest the place “turn into California.”

[* Here, the terms “California” and “Californians” stand for something broader than the named state and its residents. This is an attempt to describe a macro process and I’m simply using these specific labels because they represent the most visible and most clearly distilled example of the phenomena.]

Too many of us refuse to be governed. That applies to both zoning and national forest visitor use management.

Here’s what’s coming: https://www.travelandleisure.com/travel-news/glacier-national-park-going-to-the-sun-road-tickets-sell-out-in-minutes

And I think this helps the argument that national forests should be managed more like national parks – even moved to the Park Service because they are better at managing people.

I wonder what it means to homes in the WUI.

Is it ok if I roll my eyes at terms like, “ amenitization’s synthetic flexibility,” “capitalistic manufacture of amenities,” or “tenchnocratic wishcasting.” I’m trying to figure out what would be organic amenities versus synthetic capitalistic ones. Is this just another way to claim there is good recreation versus bad recreation? Haven’t people always been seeking amenities and moving there. The rich have always had their summer homes to escape the heat of the city. Wasn’t 40 acres a form of amenities at one time. At one time the amenities were country clubs and golf courses. People have been moving west gif the views gif a long time now. Maybe the earlier folks were more rugged and less interested in traditional comfort and culture, but dies that make them more authentic?

I think there are people who always wanted to live or second home in beautiful places. The difference is that work from home/internet/rise of retirees has allowed all these people to move where they want, where they necessarily change the place.

I think the author raises the question “what does this cycle look like and does it necessarily lead to overcrowding, over inflation of prices and the need for long term residents to move on because their offspring can’t afford to live there, ultimately to all the problems they moved away from surrounded by federal land?”

So my question would be “what communities have dealt with this, in their own view, successfully, and what did they do, and how?”.

I don’t know that anyone has come up with a solution, but I know that blaming the new arrivals is not it. Here in the Bitterroot where I live, all the trends mentioned in the article are true, if not as dramatic and have been going on for at least 30 years with an influx of retirees or other “amenity” seekers including myself who moved here 15 years ago to work a more peaceful career in the healthcare industry.

We have the old guard who want growth and no regulations and we have others who have moved here over the years with a more conservation minded attitude but still have been here for decades. This cohort wants more zoning, but in general oppose any sort of housing development. Developers are evil and adding that if we don’t build they won’t come.

So what we end up with is more high end dispersed housing in the WUI, and almost no infill or higher density development in the more urban areas.

I’ll admit I believe that like democracy, capitalist markets are still the best answer out of all the bad options. The question for me Is how to align market incentives with sustainable development. A Wild West approach doesn’t work and a just say no attitude just leads to enclaves for the rich.

Oh so all Montana is not like this postcard?

Ha ha, there are still places like that. Places without “amenities” that are struggling and losing population.

For all the hand ringing about all the growth and crowds. I don’t see anyone decamping for the plains of northeastern Montana.