I wrote the below as an introduction to a paper on zones of agreement on climate and forests. This paper was rejected by the funders, so I will post pieces here. Anyway, I’d appreciate your thoughts and any other research or links on the topic. My point was that we have many studies on how the FS operates, interviewing staff of all kinds and levels.. and yet relatively little on people and organizations who are calling the policy shots. Or maybe there is a substantial body of literature out there and somehow I missed it.

***************

Environmental groups of various kinds are powerful political actors in the US at the federal level especially around federal lands issues in the West. Their influence can occur through election funding (e.g. The Wilderness Society PAC spent $465K in one House District in New Mexico[1] in 2020, the Environmental Defense Fund $10 million[2]), through lobbying efforts to Congress and the Administration, through obtaining high-level policy positions in administrations, as well as litigation and the ensuing settlements, organizing media campaigns and grassroots lobbying. These influences appear to be growing. A review of the activity of environmental super-pacs in the 2020 election can be found in this piece[3] in E&E news. Some examples:

“NRDC President Gina McCarthy, a former EPA administrator, helped write Biden’s expanded climate and jobs plan — a level of direct, public involvement for green groups that’s virtually unprecedented in presidential campaigns.”

As stated in a letter by board chair John Dayton of Defenders of Wildlife, “Programmatic successes, unprecedented financial stability, significant advances in both development and marketing, victories in the courts, legislative efforts on the Hill and beyond and Defenders’ ever-increasing stature within the environmental community..”

Despite the importance of these organizations, a comprehensive search on Google Scholar led to very few relevant journal articles. Research is needed to understand better the influence of these organizations, how it is exerted, how their policy preferences are established internally, including, for organizations with members, the role of membership, the role of coalitions within the ENGO sector, the relationships of these organizations and media outlets, and diversity of those involved in funding and decision-making. Additionally, the complete landscape of ENGOs is difficult to describe. ENGOs are local, regional, national and international; interested in single issues or landscapes or regional, national and international.

Diversity and inclusion in the traditional sense have posed challenges to these groups (e.g. Defenders[4]) as it has to many others. This Yale 360 article[5] summarizes the situation and the work of Dorceta Taylor. In the Green 2.0[6] report of 2014, 88 percent of staff and 95 percent of boards were white. We can imagine other kinds of diversity as well, academic and work experience backgrounds, physical location (do they live in a fire-prone area?) and so on. Many of these questions have not been addressed in the academic literature.

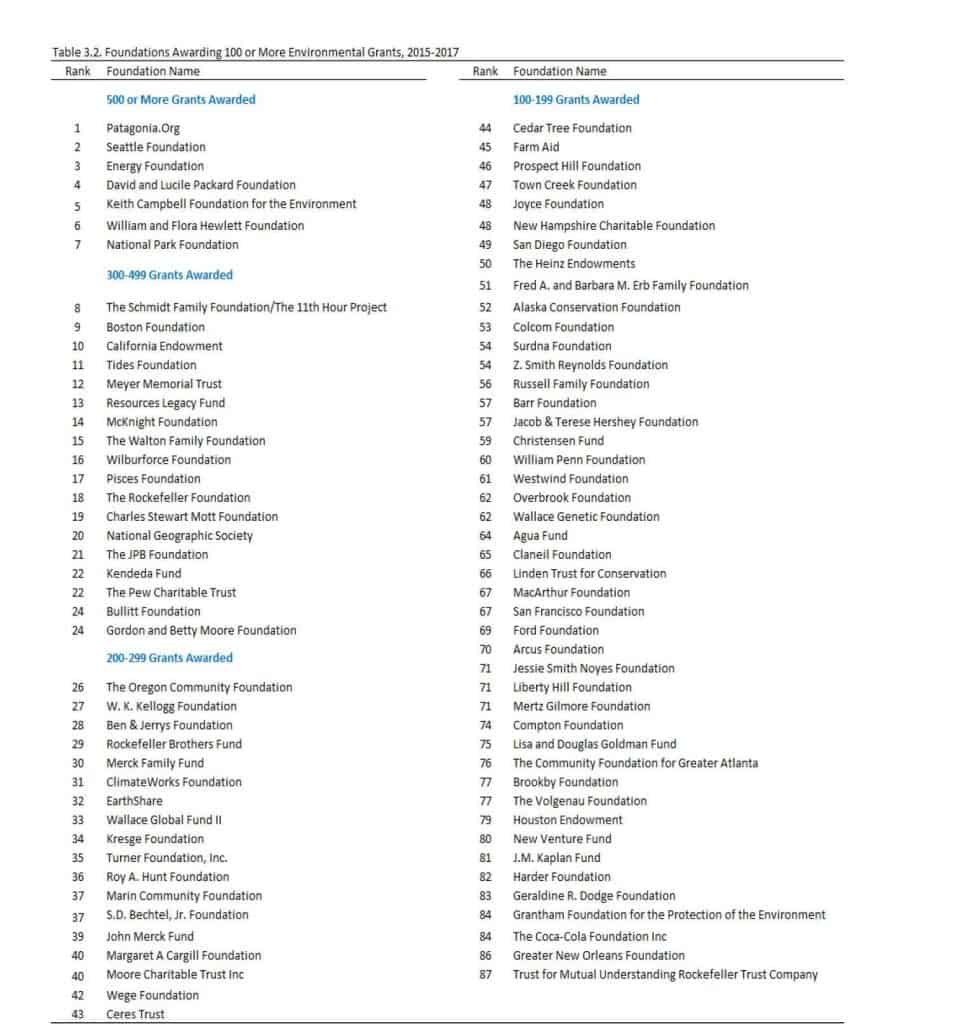

Looking one funding level up, it may also be possible that supporting charitable foundations may influence the views of ENGOs. For example, the Hewlett Foundation gave $38 million in 2020 “to conserve biodiversity and protect the ecological integrity of half of the North American West for wildlife and people.” [7] This included expenses for other groups such as the Western Conservation Foundation ($4.8 million), the National Wildlife Federation ($3.2 million), Western Energy Project ($3.6 million), Pew ($1.6 million) and others. Another example is the Wilburforce Foundation, whose grantmaking strategies in the Southwest include priorities for “permanent protection for prioritized landscapes”[8] in the Great Basin and the Southwest. It raises the question “who prioritized them?” and “what was the role, if any, of inhabitants, their elected officials, and Tribes?”

In Doug Bevington’s book “The Rebirth of Environmentalism: Grassroots Activism from the Spotted Owl to the Polar Bear”[9], he distinguishes between what he calls “grassroots biodiversity groups” and mainstream environmental groups, with litigation being the tactic of choice for grassroots groups (e.g., p. 36 “litigation was an appealing tactic for the grassroots groups because it did not necessarily require extensive resources.”) His is probably the most detailed explanation of the internal dynamics of one group, the Center for Biological Diversity. For example, on page 203 he describes the listing petitions prepared by Center attorneys who had “taken a personal interest in species outside of the issues she or he was initially funded to work on.” And states “if the activities of the staff were to be entirely determined by its funders, these listings might not have happened.”

To what extent are such donations influencing the agendas, direction, and tactics of the recipient organizations, compared to members, staff and boards? These questions could be addressed by a series of interviews such as Bevington did for his book.

Another book that examines ENGO’s strategies and tactics is Pralle’s Branching Out Digging In: Environmental Advocacy and Agenda Setting[10]. It compares the expansion and containment of conflict in the Clayoquot Sound conflict in British Columbia and compares it to the Quincy Library Group effort in California.

To summarize, there is not a great deal of academic literature available on these topics of organizational strategies, decision-making and so on among ENGOs in the United States.

There, on the other hand, is a substantial literature on ENGO’s in developing countries (e.g., Ayana et al. 2013[11]) .

As Hoberg (1997)[12] outlined, federal forest policy in the US has been effectively transformed by a strategy of ENGOs in nationalizing and taking issues to court during the spotted owl period. During this period, “local” was thought to be tied to “extractive industries.” Since then, collaborative governance and community-based participation in forest and biodiversity decisions have gained ground. There are also today’s concerns with diversity, equity and inclusion as well as openness and transparency that may raise the profile of more local voices. These developments may open opportunities for environmental peace-making with national ENGOs as local collaboratives and their networks inform the national policy discussion

[1] https://www.opensecrets.org/political-action-committees-pacs//C90018177/independent-expenditures/2020

[2] https://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/environmental-defense-fund/summary?id=D000033473

[3] https://www.eenews.net/stories/1063646455

[4] https://www.eenews.net/stories/1063733361

[5] https://e360.yale.edu/features/how-green-groups-became-so-white-and-what-to-do-about-it

[6] https://diversegreen.org/

[7] https://hewlett.org/grants/?sort=date&grant_strategies=73202

[8] http://www.wilburforce.org/programs/#pregions

[9] Bevington, D. 2009. The Rebirth of Environmentalism: Grassroots Activism from the Spotted Owl to the Polar Bear. Island Press, 2009, 285 pp.

[10] Pralle, S. 2007. Branching Out Digging In: Environmental Advocacy and Agenda Setting, Georgetown University Press.279 p.

[11] Ayana, Arts and Wiersum 2018. How environmental NGOs have influenced decision-making in a “semi-authoritarian” state: the case of forest policy in Ethiopia. World Development (109): 313-322.

[12] Hoberg, G. (1997). From localism to legalism: The transformation of federal forest policy. Western public lands and environmental politics, 47-73.