I received this as an email and copied it, so the links don’t work here. Here’s a link with lots of information. They also have recordings of their recent ScienceX program on genetics. No doubt these will also be recorded.

Forest Ecology

“Proforestation” It Aint What It Claims To Be

‘Proforestation’ separates people from forests

AKA: Ignorance and Arrogance Still Reign Supreme at the Sierra Club.

I picked this up from Nick Smith’s Newsletter (sign up here)

Emphasis added by myself as follows:

1) Brown Text for items NOT SUPPORTED by science with long term and geographically extensive validation. 2) Bold Green Text for items SUPPORTED by science with long term and geographically extensive validation.

3) >>>Bracketed Italics for my added thoughts based on 59 years of experience and review of a vast range of literature going back to way before the internet.<<<

“Proforestation” is a relatively new term in the environmental community. The Sierra Club defines it as: “extending protections so as to allow areas of previously-logged forest to mature, removing vast amounts of atmospheric carbon and recovering their ecological and carbon storage potential.” >>>Apparently, after 130 years of existence, the Sierra Club still doesn’t know much about plant physiology, the carbon cycle or the increased risk of calamitous wild fire spread caused by the close proximity of stems and competition driven mortality in unmanged stands (i.e. the science of plant physiology regarding competition, limited resources and fire spread physics). Nor have they thought out the real risk of permanent destruction of the desired ecosystems nor the resulting impact on climate change.<<<

Not only must we preserve untouched forests, proponents argue, but we must also walk away from previously-managed forests too. People should be entirely separate from forest ecology and succession. >>>More abject ignorance and arrogant woke policy based only on vacuous wishful thinking.<<<

Except humans have managed forests for millennia. In North America, Indigenous communities managed forests and sustained its resources for at least 8,000 years prior to European settlement. It is true people have not always managed forests sustainably. Forest practices of the late 19th century are a good example. >>>Yes, and the political solution pushed on us by the Sierra Club and other faux conservationists beginning with false assumptions about the Northern Spotted Owl was to throw out the continuously improving science (i.e. Continuous Process Improvement [CPI]). The concept of using the science to create sustainable practices and laws that regulated the bad practices driven by greed and arrogance wasn’t even considered seriously. As always, the politicians listened to the well heeled squeaky voters. Now, their arrogant ignorance has given us National Ashtrays, destruction of soils, and an ever increasing probability that great acreages of forest ecosystems will be lost to the generations that follow who will also have to cope with the exacerbated climate change. So here we are, in 30+/- years the Faux Conservationists have made things worse than the greedy timber barons ever could have. And the willfully blind can’t seem to see what they have done. Talk about arrogance.<<<

Forest management provides tools to correct past mistakes and restore ecosystems. But Proforestation even seems to reject forest restoration that helps return a forest to a healthy state, including controlling invasive species, maintaining tree diversity, returning forest composition and structure to a more natural state.

Proforestation is not just a philosophical exercise. The goal is to ban active forest management on public lands. It has real policy implications for the future management (or non-management) of forests and how we deal with wildfires, climate change and other disturbances.

We’ve written before about how this concept applies to so-called “carbon reserves.” Now, powerful and well-funded anti-forestry groups are pressuring the Biden Administration to set-aside national forests and other federally-owned lands under the guise of “protecting mature and old-growth” trees.

In its recent white paper on Proforestation (read more here), the Society of American Foresters writes that “preservation can be appropriate for unique protected areas, but it has not been demonstrated as a solution for carbon storage or climate change across all forested landscapes.”

Proforestation doesn’t work when forests convert from carbon sinks into carbon sources. A United Nations report pointed out that at least 10 World Heritage sites – the places with the highest formal environmental protections on the planet – are net sources of carbon pollution. This includes the iconic Yosemite National Park.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recognizes active forest management will yield the highest carbon benefits over the long term because of its ability to mitigate carbon emitting disturbance events and store carbon in harvested wood products. Beyond carbon, forest management ensures forests continue to provide assets like clean water, wildlife habitat, recreation, and economic activity.

>>>(i.e. TRUE SUSTAINABILITY)<<<

Forest management offers strategies to manage forests for carbon sequestration and long-term storage.Proforestation rejects active stewardship that can not only help cool the planet, but help meet the needs of people, wildlife and ecosystems. You can expect to see this debate intensify in 2023.

Science Friday: Reducing Tree Density in Dry Forests Can Help Drought and Insect Resistance- Bradford et al. Paper

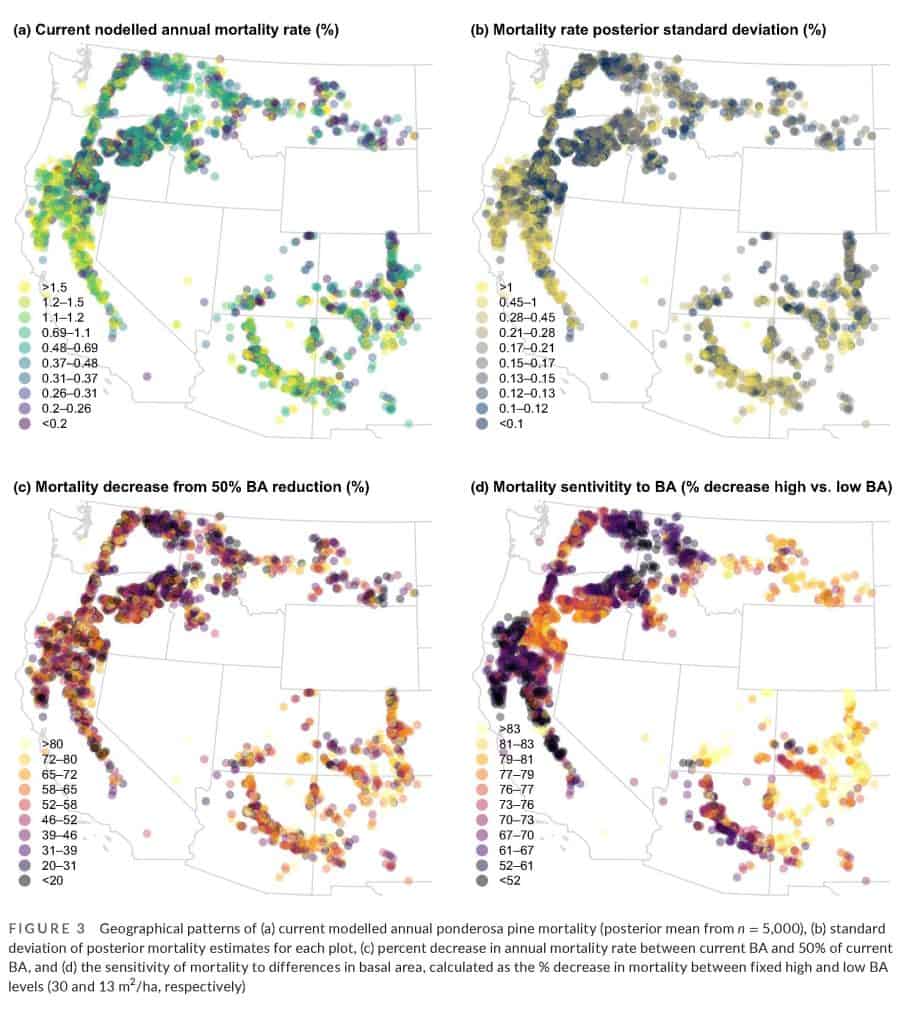

If you click on this figure twice you can see it more clearly.

I have often observed that in Oregon, dry forest management tends to be seen through a wet forest filter due to the location of most scientists, interest groups, and politicians on the West Side. So I am in no way, shape or form, suggesting that this study is applicable to wetter forests than those studied (all east of Cascades and SW Or and NW Cal). The idea is that basically in a dry forest in drought, reducing BA and competition for water will keep trees healthier. Many of us have observed this effect in the field after thinning projects and some might say that this is old news, but the authors use large datasets to come to some interesting conclusions.

This seems to be the opposite of the Williamette project in the previous post; lots of ecological reasons but no industry. In fact if you look at figure 3d, it appears that the areas that could use thinning the most (yellow) are least likely to have forest industry of any size. Do the maps make sense in the areas you know?

Here are the conclusions of this study.

Interactions between competition and drought provide information for near-term forest management. In particular, the response of mortality to drought-density interactions reinforces the climate adaptation benefits of ongoing forest landscape restoration (Stoddard et al., 2021) that is increasingly widespread in ponderosa pine forests (Figure 1a). Increasing BA in the late 20th century over many forests in the western U.S. (Rautiainen et al., 2011), particularly in ponderosa pine forests (Covington & Moore, 1994; Reynolds et al., 2013), prompted restoration projects designed to reduce forest density, promote structural conditions consistent with the historical range of variability, and mitigate the risk of catastrophic wildfires that lead to rapid loss of forest cover and ecosystem carbon (McCauley et al., 2019). The interactions demonstrated here between competition and hot drought provide quantitative information about how density reduction enabled by these restoration projects, initially designed for other purposes, will also help buffer forests against heat- and drought-driven tree mortality that is increasing in forests around the world (Allen et al., 2010). In addition, these results identify areas where BA reduction may be most useful for enhancing dry forest sustainability. Geographical patterns in estimated benefits of reducing current BA (Figure 3c,d) and in overall climate-driven sensitivity of mortality to basal area (Figure 3e) may be useful for prioritizing future restoration projects. Our results suggest that substantial reduction in BA may be necessary to moderate drought-induced mortality (Figure S4c). These treatments would alter forest structure, and the impact of those changes need to be weighed against the benefits of imposing treatments. Although severe mortality events driven by hot droughts and insects would also reduce BA, restoration treatments may include benefits like selecting the trees to removed or retain, and avoiding rapid increases in fuel loads after mortality.

Although our focus was assessing how BA and drought combine to influence tree mortality, our data include the effects of insect activity. Tree mortality is often elevated by the combination of both drought and insects (Anderegg et al., 2015). Mortality events driven by these drought–insect combinations have been demonstrated in many areas, including in ponderosa pine forests within our study area and sampling period (Fettig et al., 2019; Stephenson et al., 2019). Including these recent insect outbreaks in the data we examined ensures that our results about how mortality responds to drought type and basal area are relevant even in the context of substantial insect activity. Specifically, the potential for reducing BA to decrease tree mortality encompasses the influence of both drought (whose effects may be exacerbated by high BA due to competition) and insect dynamics (whose effects may be exacerbated by BA due to insect population dynamics not directly related to tree competition). Unlike insects, we attempted to avoid including other mortality agents by excluding plots with wildfire or harvesting. As a result, our overall average mortality rate of ~0.8% per year (5th–95th percentile = 0.14% and 1.8% per year) is an estimate of background mortality and may be less than other studies of ponderosa pine mortality (Ganey & Vojta, 2011). Drought contributes to wildfire activity (Hicke et al., 2016), underscoring the need to untangle the interacting influences of these multiple mortality agents. In addition, our results may not fully account for the consequences of actual temporal changes in climate and/or forest because we utilized a space-for-time substitution, which has recognized limitations in modelling climate-induced changes in tree mortality with a single remeasurement of FIA plots (Dietze & Moorcroft, 2011).

Forest managers have relatively few proven strategies to enhance near-term drought resistance of intact dry forests to rising temperatures and more extreme droughts. Long-term forest management strategies for climate adaptation include harvesting and/or planting to shift composition towards tree species with higher drought tolerance (Paz-Kagan et al., 2017) or to promote forests with higher diversity in species composition or functional traits (Anderegg et al., 2016). Reducing BA in existing forests is a complementary and feasible strategy that our results suggest will have long-term benefits. The interactions identified here provide insight into the types of drought that most influence tree mortality, and how those drought conditions can be minimized by moderating competitive intensity. Specifically, BA reduction can enhance resistance to hot conditions and to multiyear drought events, whose frequency and severity are also expected to be increased as a result of elevated hydro-climatic variability (Swain et al., 2018). This elevated hydro-climate variability may create more multiyear wet periods that could enhance mortality in subsequent droughts by promoting structural overshoot (Jump et al., 2017), further highlighting the benefits of density reduction. Predictions of multiyear wet periods (Liu & Di Lorenzo, 2018) may represent important opportunities for intensive management (e.g. thinning) to promote forest structural conditions with high resilience to hot droughts (Bradford et al., 2018). Our findings that basal area interacts strongly with multiyear drought, and that 3-year wet periods partially mitigate ponderosa pine mortality, provide evidence that both the interactions and the occurrence of wet periods may be useful focal points for additional synthesis and analysis.

Possible Salvage Strategy for Dixie and Caldor Fires

Since a battle for salvage projects is brewing, I think the Forest Service and the timber industry should consider my idea to get the work done, as soon as possible, under the rules, laws and policies, currently in force. It would be a good thing to ‘preempt’ the expected litigation before it goes to Appeals Court.

The Forest Service should quickly get their plans together, making sure that the project will survive the lower court battles. It is likely that such plans that were upheld by lower courts, in the past, would survive the inevitable lower court battles. Once the lower court allows the project(s), the timber industry should get all the fallers they can find, and get every snag designated for harvest on the ground. Don’t worry too much about skidding until the felling gets done. That way, when the case is appealed, most of Chad Hanson’s issues would now be rendered ‘moot’. It sure seems like the Hanson folks’ entire case is dependent on having standing snags. If this idea is successful, I’m sure that Hanson will try to block the skidding and transport of logs to the mill. The Appeals Court would have to decide if skidding operations and log hauling are harmful to spotted owls and black-backed woodpeckers.

It seems worth a try, to thin out snags over HUGE areas, while minimizing the legal wranglings.

Science is clear: Catastrophic wildfire requires forest management

“Science is clear: Catastrophic wildfire requires forest management” was written by Steve Ellis, Chair of the National Association of Forest Service Retirees (NAFSR), who is a former U.S. Forest Service Forest Supervisor and retired Bureau of Land Management Deputy Director for Operations—the senior career position in that agency’s Washington, D.C., headquarters.

I have extracted a few snippets (Emphasis added) from the above article published by the NAFSR:

1) Last year was a historically destructive wildfire season. While we haven’t yet seen the end of 2021, nationally 64 large fires have burned over 3 million acres. The economic damage caused by wildfire in 2020 is estimated at $150 billion. The loss of communities, loss of life, impacts on health, and untold environmental damage to our watersheds—not to mention the pumping of climate-changing carbon into the atmosphere—are devastating. This continuing disaster needs to be addressed like the catastrophe it is.

2) We are the National Association of Forest Service Retirees (NAFSR), an organization of dedicated natural resource professionals—field practitioners, firefighters, and scientists—with thousands of years of on the ground experience. Our membership lives in every state of the nation. We are dedicated to sustaining healthy National Forests and National Grasslands, the lands managed by the U.S. Forest Service, to provide clean water, quality outdoor recreation, wildlife and fish habitat, and carbon sequestration, and to be more resilient to catastrophic wildfire as our climate changes.

3) As some of us here on the Smokey Wire have been explaining for years, the NAFSR very clearly and succinctly states:

“Small treatment areas, scattered “random acts of restoration” across the landscape, are not large enough to make a meaningful difference. Decades of field observations and peer reviewed research both document the effectiveness of strategic landscape fuel treatments and support the pressing need to do more. The cost of necessary treatments is a fraction of the wildfire damage such treatments can prevent. Today’s wildfires in overstocked forests burn so hot and on such vast acreages that reforestation becomes difficult or next to impossible in some areas. Soil damage and erosion become extreme. Watersheds which supply vital domestic, industrial, and agricultural water are damaged or destroyed.”

4) This summer, America watched with great apprehension as the Caldor Fire approached South Lake Tahoe. In a community briefing, wildfire incident commander Rocky Oplinger described how active management of forestlands assisted firefighters. “When the fire spotted above Meyers, it reached a fuels treatment that helped reduce flame lengths from 150 feet to 15 feet, enabling firefighters to mount a direct attack and protect homes,” The Los Angeles Times quoted him.

5) And in a Sacramento Bee interview in which fire researcher Scott Stephens was asked how much consensus there is among fire scientists that fuels treatments do help, he answered “I’d say at least 99%. I’ll be honest with you, it’s that strong; it’s that strong. There’s at least 99% certainty that treated areas do moderate fire behavior. You will always have the ignition potential, but the fires will be much easier to manage.” I (Steve Ellis) don’t know if it’s 99% or not, but a wildfire commander with decades of experience recently told me this figure would be at least 90%. What is important here is that there is broad agreement among professionals that properly treated landscapes do moderate fire behavior.

6) During my career (Steve Ellis), I have personally witnessed fire dropping from tree crowns to the ground when it hit a thinned forest. So have many NAFSR members. This is an issue where scientist and practitioners agree. More strategic landscape treatments are necessary to help avoid increasingly disastrous wildfires. So, the next time you read or hear someone say that thinning and prescribed fire in the forest does not work, remember that nothing can be further from the truth.

One Experimental Forest- Super-Sized : OSU and Elliott State Forest

Thanks to Peter Williams for this one, reported in Nature.

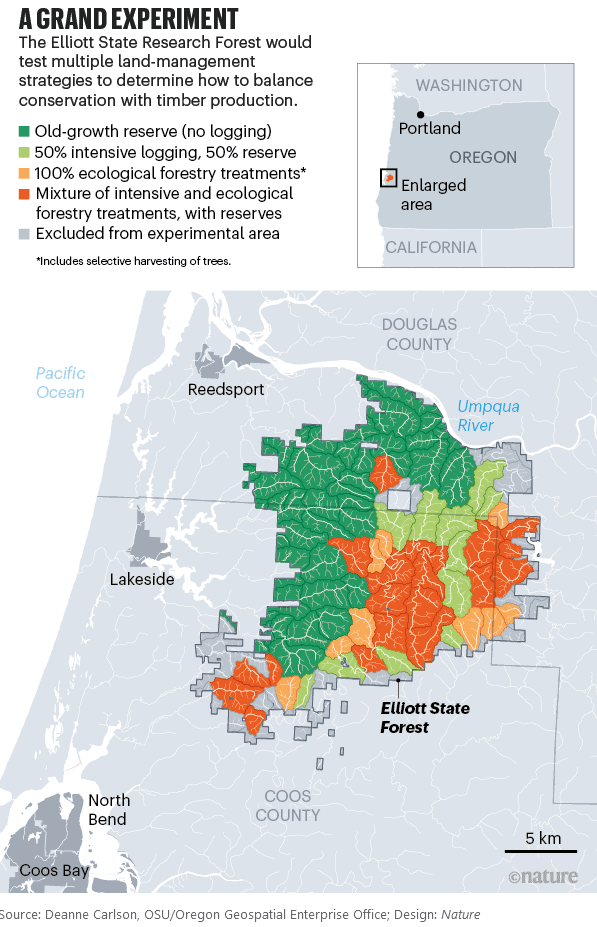

If the project — proposed by DeLuca and other researchers at OSU — launches successfully, the newly created Elliott State Research Forest in southwestern Oregon would occupy a roughly 33,000-hectare parcel of land. This would be divided into more than 40 sections, in which scientists would test several forest-management strategies, some including extensive logging. The advisory committee for the project, which comprises environmentalists, hunters, loggers and members of local Indigenous tribes, approved the latest research proposal on 22 April.

Controversially, the study would allow logging in a new research forest, in an attempt to answer a grand question: in a world where wood remains a necessary resource, but biodiversity is declining, what’s the best way to balance timber production with conservation?

Well, it will answer that question at least for areas similar to Elliot State Forest, anyway, or at least illuminate trade-offs. Is it controversial to allow logging in a new (or old) research forest? Most of them, at least on Forest Service land, were established to do precisely that. Here’s a link and map of all Forest Service Experimental Forests and Ranges. At least two of them, H. J. Andrews in Oregon (16K acres) and Hubbard Brook in New Hampshire are also Long Term Ecological Research units and get infusions of funding from NSF.

It’s also interesting that some environmental groups are on the advisory committee, while others think clearcutting shouldn’t occur at all, and others don’t trust OSU. The advisory committee would conceivably review plans for specific sites, though, so mistakes like the 16 acre old growth one shouldn’t occur in the future.

Questions:

“As currently designed, the project would leave more than 40% of the forest — a section of old growth that has been regenerating naturally since the area last burnt, a century and a half ago — untouched by logging.”

Is 150 years old considered “old growth” in that area? Or are there pockets of old-growth in the burned area that will be untreated?

But the Elliott research forest would be larger than most of its predecessors, and advocates say that it would provide scientists with the first opportunity to test ecological forestry at such a large scale.

I’m curious about the larger ones.. the H.J. Andrews is “only” 16,000.. I wonder where those larger ones are? I also wonder what are the kinds of specific questions for which you need more than 10,000 acres of designed experiment to answer.

Totally off the subject side note: I ran across this while looking at the (excellent) H.J. Andrews website. I found it a bit disconcerting.

CONSERVATION ETHICS

Natural resource management can be seen as a set of practices, which reflect certain ideas about the world. Ideally management practices will be consistent with our best scientific ideas about the workings of both biophysical and social systems, but management practices also and inevitably manifest our ideas about what is good, what is right, and what is valuable. For example, we manage riparian zones in certain ways because we understand certain relationships between riparian zones and streams and rivers; but also because we believe certain management practices will achieve important goals, or protect important values, related to streams and rivers. In this way, management fuses science and ethics.At the Andrews Forest, we consider ethics an inherent part of our work. We seek not only to understand how ideas work in socio-ecological systems, but also to explicitly consider how they ought to work, particularly at the interface of science and management. Formal methods of critical thinking, or argument analysis, are used to understand and evaluate both the science and ethics of management decisions, predicated on the belief that decisions made through such a process of sound and rigorous reasoning will be more systematic, more transparent, and ultimately more reasonable than they might otherwise be.

I didn’t learn much about ethics in my science education, except research ethics. I grant you that my education was a long time ago. Still, I found it pretty fascinating that the scientists are “explicitly considering how social systems (well, at least socio-ecological systems) “ought to” work. Because it sounds like “we reason more reasonably than people who make management decisions” or “we are more attuned to ethics than they are.” I’m not sure that there’s relevant social science research behind either claim.

North Versus Hanson

“Use every damn tool you’ve got,” he said. “If we could have beavers on crack out there I’d be donating to that process — anything that will speed up the pace and scale of this thing.”

Dr. Malcolm North

Hundreds of Giant Sequoias Considered Dead From Wildfires

It appears that rumors of ‘natural and beneficial’ wildfires in the southern Sierra Nevada have been ‘greatly exaggerated’. Even the Alder Creek grove, which was recently bought by Save the Redwoods, was decimated. Of course, this eventuality has been long-predicted.

https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2020-11-16/sierra-nevada-giant-sequoias-killed-castle-fire

Patterns and Drivers of Recent Tree Mortality in Diverse Conifer Forests of the Klamath Mountains, California

Thanks to the Society of American Foresters for posting a western round-up of papers in Forest Science and Journal of Forestry. I thought that this one was particularly interesting from several standpoints.Here’sa link.

1. Just because we leave trees alone doesn’t mean they will continue to do carbon storage. Maybe this works in the rain forests, but not so much where the cycle is “trees get established, get dense without fire, water can’t support so many trees and/or trees grow old, get bugs and diseases and die”.

2. It’s really hard or impossible to tease out how much of this mortality is due to changes in climate, past fire suppression, changes in bug and diseases, age of trees and so on, because through time they are all correlated. Back in the day when we wanted to tease out interactions, we would design experiments to do that. We could plant trees every 20 years, run fires through at different intervals, and wait 100 years (or 250) for our answer, except the climate would be changing all that time. So perhaps it’s time to simply say “we won’t know for the foreseeable future- if ever, but if it is climate we should do x, and if it’s age, we should do y, and if it’s fire suppression we should do z. Are x, y and z all that different? How sure are we that they will “work”? How much will they cost? What if we don’t do anything?”

3. From a pragmatic point of view, we need to consider a concept I’ll call “cats out of the baggery”.. one being climate change, and the other being non-native species. Even if we stopped climate change today, and kept all new non-native pests and pathogens from entering the country, managers would still have to deal with existing effects. Or not, in the case of this study, because it’s a Wilderness.

4. Philosophical question: the authors state.

Since this disease complex was first described in 1984, several management recommendations were made to increase the health and vigor of Shasta red fir stands, including selective removal of severely infested trees, and clearcutting and regenerating in heavily infested stands (Kliejunas and Wenz 1982). As of 2010, these silvicultural treatments were not yet prescribed and forest health continued to decline at this site (Angwin 2010), and in 2015, many of the severely infested stands burned in a wildfire (personal communication, Keli McElroy, USFS). Fire may be the best management strategy for slowing the spread of the disease complex, particularly in wilderness regions where silvicultural treatments are not feasible.

I think since it’s in Wilderness, management would mean simply mean no intervention, except maybe WFU?

5. It makes me wonder how much of what we think is conditioned by the most-studied forest areas. Note below how the Klamaths are different from other studied areas.

(CWD is climatic water deficit).

Several authors attribute recent die-off events to initial abiotic stress that predisposes trees to other agents of mortality, such as pests and pathogens. The region-wide dieback of piñon pine (Pinus edulis Engelm.) in the southwestern United States, for example, was attributed to the 2000–2003 drought accompanied by unusually high temperatures, which predisposed trees to attack by a secondary bark beetle species, Ips confusus LeConte (Breshears et al. 2005). Similarly, Millar et al. (2007) found that limber pine mortality in the Sierra Nevada was linked to increased temperature and decreased precipitation, followed by dwarf mistletoe, and finally by mountain pine beetle. We do not see surmounting evidence that recent tree mortality in our study area is linked to unusually high summer temperatures, as the rising temperature trend we observe is driven by minimum temperatures and is most pronounced in winter months (Figure S4, Figure 3). Our study is consistent with literature suggesting that fir engraver outbreaks are associated with increased evapotranspiration (Wright and Berryman 1978, Berryman and Ferrell 1988); however, similar to Rapacciuolo et al. 2014, we did not see an increase in CWD. This distinguishes our study from many other tree mortality studies in the Sierra Nevada, for example, where die-offs have been attributed to large increases in CWD in recent years (Millar et al. 2012, Mcintyre et al. 2015). Finally, we used a ten-year window (2004–2014) for calculating recent changes in climate parameters, but it is possible that a few years of extreme drought within this period could have accelerated mortality, as has been shown in other systems (Breshears et al. 2005). For example, the 2011–2014 regional drought almost certainly created physiological challenges for Shasta red fir trees that exacerbated drought stress from dwarf mistletoe, and increased susceptibility to fir engraver infestation, but further investigation is needed to tease apart the abiotic vs. biotic causal agents of mortality.

Changes in the historical disturbance regime of these forest types, particularly the effects of fire exclusion, may be partially responsible for the elevated levels of recent mortality in high density and/or more mature stands throughout our study area. Similar to other parts of California, forests in the Klamath region have notable signs of fire exclusion, including in-filling of small, shade-tolerant trees (typically white fir), and dense accumulations of litter and duff around older trees. Historically, this region is characterized by a mixed-severity fire regime, with a high frequency of fires prior to the twentieth century producing mostly low and moderate fire effects in most conifer vegetation types (Skinner et al. 2006). In the upper montane zone (where we observed the highest mortality), the estimated fire return interval based on studies done in nearby forests ranges from about 15 to 41 years (Taylor and Halpern 1991, Taylor 2000) According to Forest Service records, our study area has not burned in the past 100 years (Safford et al. 2011), and based on the aforementioned estimates, we determine that the upper montane zone in our study area has missed somewhere between two and six fire cycles. Our finding of higher mortality among smaller diameter trees is consistent with a growing body of literature suggesting that increased stand density and competition from fire exclusion are major contributing factors to the increasing mortality trend in western coniferous forests (Guarin and Taylor 2005, Maloney 2011, Millar et al. 2012). Furthermore, high stand density has been shown to amplify drought stress (Gleason et al. 2017) and increase the spread of pests and pathogens. While some of the mortality observed in this study is undoubtedly related to self-thinning in high density stands, the usually high numbers of recently dead and dying Shasta red fir trees (28%) coupled with the high levels of pathogens and forest insects is more indicative of a die-off event versus a slower change in community composition. In this case, the die-off was almost certainly precipitated by at least a decade of damage from dwarf mistletoe and Cytospora infestation.