We haven’t come back to Ryan Sabelow’s question for a while. He said

“I would love to see the results of a survey of district rangers, local forest NEPA people and biologists on the challenges of doing this work on a landscape level.”

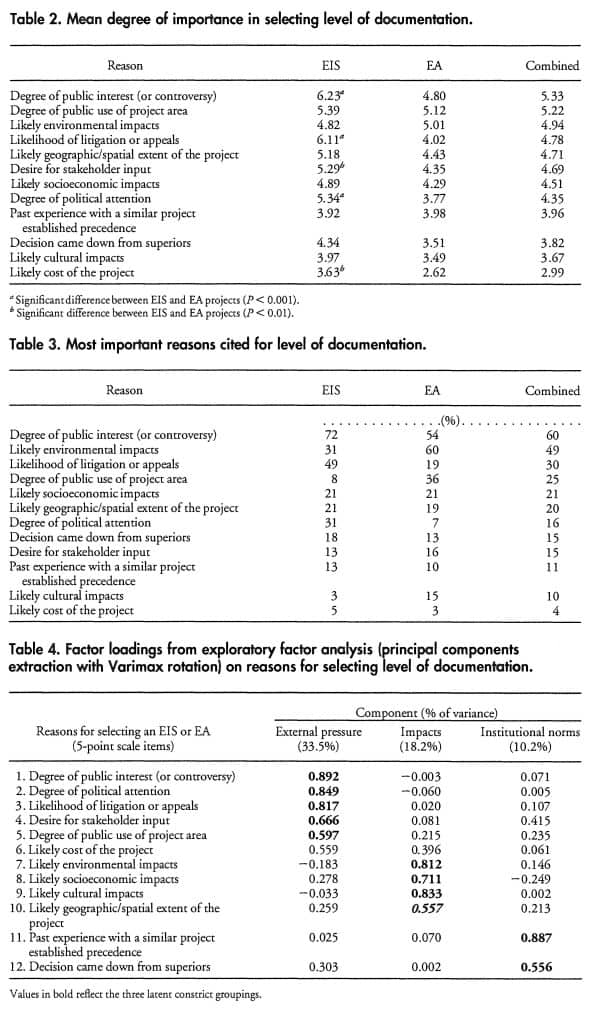

Certainly there are plenty of financial and organizational challenges, as have been studied. But specifically about NEPA, the closest I could find was this Mortimer et al. paper from the Journal of Forestry in 2011, funded and developed through the NEPA for the 21st Century research project. There’s a great deal of interesting information in this short paper. I think it would be helpful for practitioners today to engage with this paper and its findings.

Let’s look at the methods first.

This article is an amalgam of three related research efforts, each with its own methodological approach. The first was a qualitative pilot study relying on primary environmental document analysis and subsequent in-depth personal interviews with 25 respondents in the US Forest Service (n = 8), the National Park Service (n = 6), the Bureau of Land Management (n = 9); and the US Army Corps of Engineers (n =2) in the winter of 2006-2007.

These numbers seem low (though I’m not a social scientist) and this was a while (15 years) ago.

On Mar. 20, 2008 an invitation to participate in an online survey was sent to all identifiable ID team leaders of recreation-related NEPA processes within the US Forest Service involving the issuance of an EA or EIS between December 2005 and March 2008.

Why recreation projects? The authors have a variety of reasons, including the importance of travel management at that time. Still, I would have selected vegetation management projects.

As such, these projects typify the complexities of many other types of projects involving multiple stakeholders and are squarely within the dominant paradigm of multiple uses of the national forests.

The third study analyzed all federal court cases filed from Jan. 1, 1989 to Dec. 31, 2006, in which the US Forest Service was a defendant in a lawsuit challenging a “land-management” decision.

The authors focused on wins and losses on the NEPA claims.

Here are some quotes:

The interviewees presented several themes for preferring an EIS over an EA that went beyond the considerations outlined in the CEQ regulations: [4J

• The threat of litigation and the ability to withstand legal challenges:

“Our solicitors push us to, they would much prefer us to do an EIS because it’s easier to defend in court.”

“The decision with sometimes doing an EIS is whether it’s going to litigation or not …”

• The desire or ability to incur or demonstrate significant environmental impacts on the landscape with an E1S:

“If you really want me to have an EIS, then I’m going to go for the gusto and have some significant impacts.”

“We had no idea what the outcome was going to be, hut with an EI5 you can have a significant effect. And we wanted to have a significant effect on the landscape.”

• The level of public controversy:

“If you have more than a 30% suspicion that if you try to go the EA route someone is going to stop you or threaten to sue you, you’re better to … put your NOI out and circulate a draft EIS.”

I’m not sure that the above is still true, but it was in my day. In fact, we often have the “they should have done an EIS discussion” here on TSW.

Here’s what they came up with numerically:

Possibly discussion-worthy parts of the conclusions..

On the other hand, excessive analyses have delayed critical decisions and commonly produce unintelligible documents of little usefulness to any audience, which may often obfuscate rather than disclose or clarify agency decision making processes (Sullivan et al. 1996, US Forest Service 2002, Stern and Mortimer 2009). Our study suggests that a more detailed understanding of how ecological risks and social risks influence agency environmental analyses could further illustrate the extent to which process risk aversion influences the achievement of the intents of the NEPA and agency objectives concerning land management.

And:

Any assessment of risk particular to litigation and the NEPA process is inherently subjective and uncertain. For example, our findings contradict the prevailing wisdom among agency respondents that an EIS is more legally robust than an EA and, therefore, preferred when litigation over a project is expected. Although we focused specifically on travel management projects, data suggest that at a broader scale the pattern of document defensibility is similar (Table 7). As such, each of these behaviors may be contributing to the well-accepted notion that the agency’s resource management obligations have been compromised by excessive an.d unnecessary analysis (US Forest Service 2002) in efforts to strengthen certain areas of the NEPA document and the administrative record.

A point I would have made, had I reviewed this paper, is that there are other key actors that have a role in the EA/EIS decision; those being OGC for USDA or Solicitors from BLM. This is difficult, as with so many aspects of litigation, I’m not sure they are allowed to participate in surveys (?). It doesn’t really help to tell FS NEPA practitioners what the “data show” if the folks who need to be convinced are the in-house counsel. I would be very interested in hearing from those retirees; so far my efforts to rope them in to these discussions have been unsuccessful.