I received a link to this article just about the same time I was hearing about the re-Monumentization effort and the language of the Reconciliation bill. Another Biden Administration claim, for example, here “promise that they would summon “science and truth” to combat the coronavirus pandemic, climate crisis and other challenges.” And that raises the question of course “what specific scientific studies support this claim?” and “who determines what is truth?” What’s the role of “science” compared to other views and interests?

Here’s a link to a Conversation article.

And here’s the abstract.

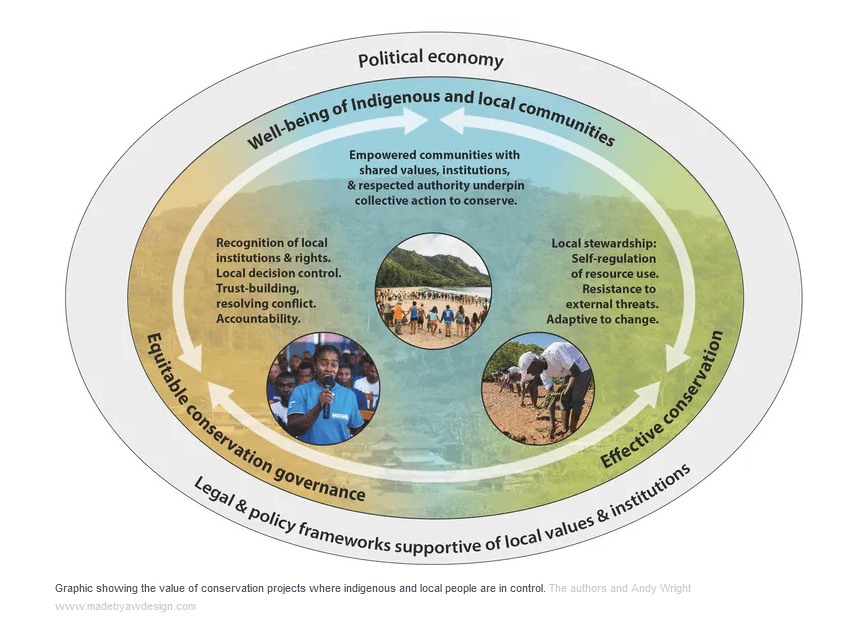

Debate about what proportion of the Earth to protect often overshadows the question of how nature should be conserved and by whom. We present a systematic review and narrative synthesis of 169 publications investigating how different forms of governance influence conservation outcomes, paying particular attention to the role played by Indigenous peoples and local communities. We find a stark contrast between the outcomes produced by externally controlled conservation, and those produced by locally controlled efforts. Crucially, most studies presenting positive outcomes for both well-being and conservation come from cases where Indigenous peoples and local communities play a central role, such as when they have substantial influence over decision making or when local institutions regulating tenure form a recognized part of governance. In contrast, when interventions are controlled by external organizations and involve strategies to change local practices and supersede customary institutions, they tend to result in relatively ineffective conservation at the same time as producing negative social outcomes. Our findings suggest that equitable conservation, which empowers and supports the environmental stewardship of Indigenous peoples and local communities represents the primary pathway to effective long-term conservation of biodiversity, particularly when upheld in wider law and policy. Whether for protected areas in biodiversity hotspots or restoration of highly modified ecosystems, whether involving highly traditional or diverse and dynamic local communities, conservation can become more effective through an increased focus on governance type and quality, and fostering solutions that reinforce the role, capacity, and rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities. We detail how to enact progressive governance transitions through recommendations for conservation policy, with immediate relevance for how to achieve the next decade’s conservation targets under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.

Now there’s at least two interesting things about this paper. It uses “Indigenous and local communities” as a unit. Here within the US, there seems to be great interest in empowering Indigenous communities (at least as long as they agree with certain interests) but perhaps, not so much, local communities. If a community doesn’t want, say, wind turbines, they may be called NIMBY’s. If they do want to produce wood products, they are not in the pockets of extractive interests. And I know that people in local communities disagree among themselves, as do Native Americans. And who wins is ultimately a political/privilege question. Still, I think this would argue for some kind of process that involves all these affected parties directly and transparently.

In the paper, conservation is a bigger idea than what we might think of conservation.. it’s kind of “everything good.”

This review builds on the idea that beyond its environmental objectives, conservation serves to support the rights and well-being of IPLCs. We wish to explore not only the social outcomes of conservation, but also the social inputs, including values, practices, and actions (specifically of IPLCs) that may shape the social and ecological outcomes of conservation. In so doing, we adopt a definition of well-being that is holistic and adaptable to different contexts, encompassing not only material livelihood resources such as income and assets but also health and security as well as subjective social, cultural, psychological, political, and institutional factors (Gough and McGregor 2007). All of the latter elements are increasingly considered as potential social impacts of conservation (Breslow et al. 2016).

(my bold)

It strikes me in focusing on local-led efforts, the Biden Admin 30×30 is following along with these concepts (perhaps “the science”). On the other hand, there appear to be political forces at work to assuage interests who feel quite differently about local processes and involvement (not sure what degree of Tribes), as per re-Monumentization and the Reconciliation bill. It will be interesting to watch how the Administration navigates these tensions through time.

I love this paper but would also urge caution applying its findings to the management of public lands in the US, when it contains no cases from that context (there is only 1 study I can find in the appendix that is of a mainland US case – focused on the Yurok tribe in N. CA). Having worked in many of the international contexts described in the cases drawn on for this paper, I’ll just say that the local communities I know near national forests in the US are in some ways similar and in many ways quite different from those I’ve studied near forests in Mexico and India (where a whole bunch of the cases reviewed in this paper are from).

I agree that local communities here might be different if the goal were strictly “biodiversity preservation” results quantified. What we might call the “instrumental”.. involving local people is good because “we” (ENGOs) get what we want more effectively.

But… this paper asserts

“Conservation serves to support the rights and well-being of IPLCs.” The idea of rights and well-being to me implies something larger.. some right to some kind of agency in decisions that affect them about their environment.

I guess I’m not sure I understand your comment. Having worked in the western US a bit, and in India more recently, I see really fundamental differences in these contexts in the kinds of political rights and opportunities that local people have. To put the matter rather plainly, in rural India, except where there is really powerful local leadership and formalized rights arrangements (and sometimes even when this is in place), local people have absolutely zero say in how forests are managed. By contrast, local people living near federal lands in the US have very substantial political rights to express their opinions and participate in decision-making both through formalized processes (e.g. through NEPA and NFMA and associated public comment processes) and a wide variety of informal political processes at multiple levels (e.g. our recent research suggests that local politics has a fairly direct influence on agency decision-making beyond notice and comment procedures – https://academic.oup.com/jpart/advance-article-abstract/doi/10.1093/jopart/muab037/6364117). And local people in the US often exert leadership over decision making on forest lands because unlike in India, in the US individuals, tribes, and local governments own forest land, and also have various opportunities to exert leadership over the management of public land. In India, I can say rather clearly that these research findings point to the necessity of increasing opportunities for local people to lead natural resource management decision-making. In the US, numerous opportunities already exist to make this happen and there is also clearly room for improvement but I’m not very clear which improvements would be substantively important to make this happen, and I also keep reading on this blog about how public involvement processes are costly and expensive and prevent work from getting done, and while I’m skeptical of these claims, I don’t dismiss them out of hand but recognize that there are likely significant tradeoffs between “increasing local control” which might mean more costly public participation and “getting things that scientists or managers think need to get done done.” This is fundamentally why I’m cautious about interpreting this research for the management of US public lands.

Dr. Fleischman: Thank you for sharing your expert, and excellent, perspective on this matter.

“Indigenous and local communities” Lately I’ve been reading things by a woman who kind of considers indigenous and local people to be pretty much one and the same. She herself is of mixed Apache and Hispanic heritage. She finds very much in common between indigenous, Hispanic, and Anglo locals, and calls the second home moved out from LA, or vacationing on public lands set, “colonizers” and “settlers”. Using the woke language back-at-em.

Talking to locals in Escalante a couple of years ago it seemed like they objected more to the imposition of edicts from on high than to any sort of land use restrictions of the monument designation. Also the influx of highly compensated government archeologists, hydrologists, biologists, etc, and all their hangers on were changing the character of those little southern Utah towns that would just as soon stay forgot.

I always think back to my favorite Peter Kareiva quote, saying something about the people most affected by a conservation measures should have the most influence about how or if that measure is implemented

Som.. I think the Peter Kareiva quote is a justice/equity/inclusion kind of idea. I think it’s also related to the (Catholic) principle of subsidiarity. Which I think is part of their social justice thinking.