From Emily Dohlansky (many thanks!):

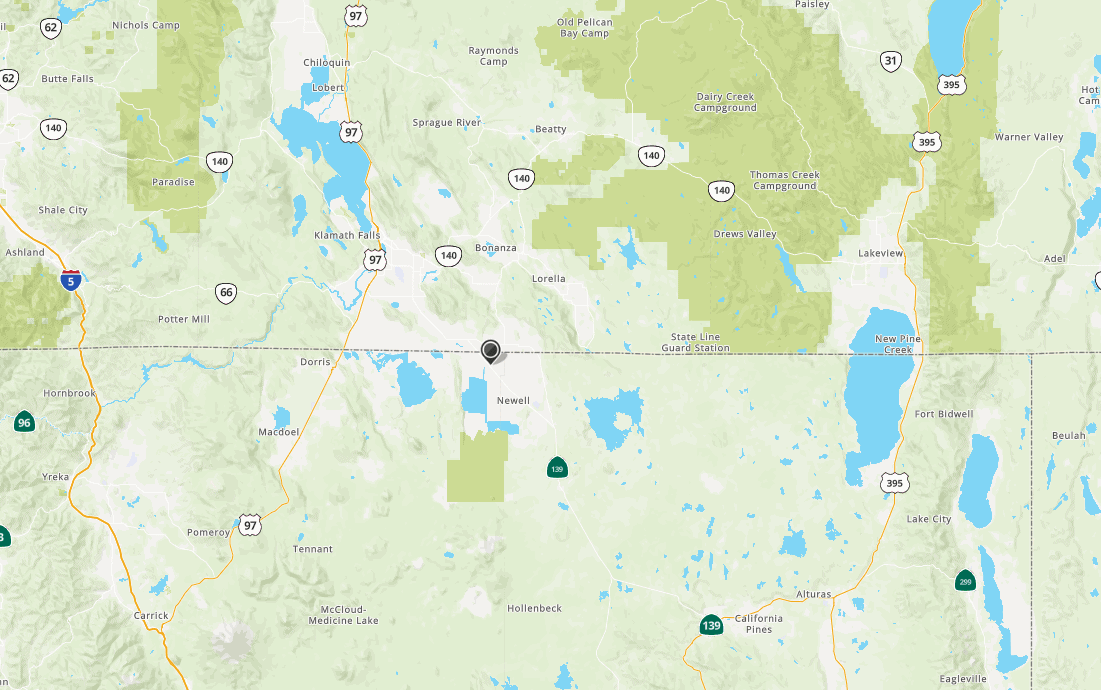

“The Sacramento Bee recently published a five-part series on Northeastern California that challenges the concept of “wild” places in the state. I found all of the articles fascinating and well-balanced. The one on wild horses garnered a lot of negative feedback from advocates, and wild horse management isn’t something that I see mentioned here often. I thought it would be interesting to have a discussion about the articles, their shortcomings, and a path forward in this “post-wild” world.”

I think each one is interesting enough to deserve a separate post, so let’s start with the first one:

WE’RE NOT GOING BACK TO THE STATE OF NATURE’

State and federal regulators and scientists, meanwhile, are largely paralyzed to do anything about any of it, thanks to a constantly growing array of regulatory demands that suck up their budgets and staff time. There is very little innovation in the public’s lands and wildlife management these days.The threat of lawsuits from the competing interest groups makes restoring even a few acres of habitat a years-long process of expensive studies, planning and lawyering. Deviate one inch from a “management plan” that’s already been hashed out in the courts, the agency will almost certainly get sued again, or some politician loyal to a faction will come in and pass a law or change a rule to make the agency’s job even harder.

And the places I love are worse for it.

To try to save some of what’s left of these habitats, it will require a clear-eyed look at how we think about, fund and manage our lands and wildlife. It also will need to come with an acknowledgment from those living in major cities that these places aren’t truly “wild,” and they haven’t been for more than a century.

“We can’t just walk away,” former California Gov. Jerry Brown told me. “We’re not going back to the state of nature, but we should try to advance environmental goals, and at the same time we have to respect people, their livelihoods and their traditions. It’s a messy process.”

At their heart, these stories are about how the land-use decisions of the past have collided with divisive partisan politics, lack of funding, inattention and bureaucratic paralysis to create crises that are only going to get worse for both the ecosystems and the impoverished rural towns that make up my favorite corner of the state.

A bit of history here…

“In the timber, a century of aggressive logging cut down the largest trees that were best able to survive the sorts of cleansing, low-intensity fires that crept along the forest floor every few years before white settlement.”

It isn’t clear when the “century” was.. but I came into this country (just north on the Fremont) in 1979, 40 years ago now. We were using Keen’s classification, or what some called “pick and pluck”.. later in the early 80’s. It identified trees on the likelihood of their getting eaten by pine beetles, not just because they were large. Weyerhauser was doing clearcutting. Folks from OSU came over and told us we should be clearcutting (it was the “latest science”). Meanwhile, Region 5, just to the south in California was not doing that much timber-wise. What I’m saying is basically it’s a lot more complicated throughout that area depending on ownership.

“Now, much of the public’s timberlands have grown unnaturally dense with small trees and brush, choking out wildlife and allowing wildfires to grow exponentially more destructive. Adjacent private timberlands that had previously been clear-cut are now often little more than tree farms, sprayed with herbicides to kill the brush and shrubs competing with the replanted timber.”

Here’s a forest ownership map of Oregon https://oregonforests.org/content/forest-ownership-interactive-map. I found a few of California but nothing quiet as clear about industrial forest ownerships. https://images.app.goo.gl/NDYJGGfNAXRnGPWKA

My point being that I’m not sure there are that many acres of intensively managed forests in that area. Also the author didn’t mention Native American burning practices, the effects of removing Native Americans from the landscape. The Modoc War war ended in 1873.

Perhaps some readers are around from these periods that can share reflections on the silvicultural history of the area?

Hello Sharon, Cameron Miller of Redding here. If you look on google earth you’ll find plenty of active even-aged management occurring in eastern Shasta, Siskiyou, Modoc, and Lassen counties. Sierra Pacifc, WM Beaty, Roseburg and other smaller firms all manage these lands. There is also a state forest (Latour) and of course FS ownership.

Well I think that’s my point. When I think of eastern Modoc County, I think of the Warner Mountains, that had a logging period from 1920-1950 with not a lot since. To me that’s different from current private intensive management practices.

Then I think there’s former clearcuts on federal land that may still look like clearcuts from satellites due to the fact that trees don’t grow very fast.

Sounds like a field trip is needed post Covid.

There isn’t much threat of environmentalist lawsuits against forest thinning projects in the Sierra Nevada National Forests. That’s an insanely-popular scapegoat for right-wingers, today. However, just doing a few thousand acres of thinning, per year, per Ranger District, isn’t going to mitigate much.

That is true of Sierra Nevadan forests due to the advocacy of local communities such as the Quincy Library Group and certain RCDs. But the actual/perceived threat of lawsuits *is* happening elsewhere (I believe R1 is the most-often litigated; thus, outside the scope of this series) and this has been well-documented in research on barriers to implementing vegetation projects on NFS land. Also, I would not say the author is right-wing (even though I don’t think that’s what you were implying). I follow him on Twitter and he definitely leans left, hence why this is a well-balanced series in my opinion. He includes a variety of perspectives across the environmental spectrum.

I agree that a few thousand acres of thinning every year isn’t going to “mitigate” much. But isn’t fire mitigation, as a one-dimensional management objective, what set us up for failure a century ago? This is also how I view management for the NSO, or fuels reduction, or any other objective with a singular goal in mind. Anything that deliberately pushes a forest toward an even-aged, stagnant system is…a bad technique. But that’s hard enough to convey to my coworkers, let alone the general public. 🙂

There are multiples ‘purposes and needs’ that are addressed by “thinning from below”. There can be a balance between thinning benefits, short term impacts and mitigating treatments.

I’m sure there could be a total amount of treatable acres, a total amount of non-treatable acres and an amount of treated acres. That should provide some perspective about what commercial ‘logging’ can do (and can’t do), in the Sierra Nevada. There are a great many acres that cannot be thinned, for various good reasons.