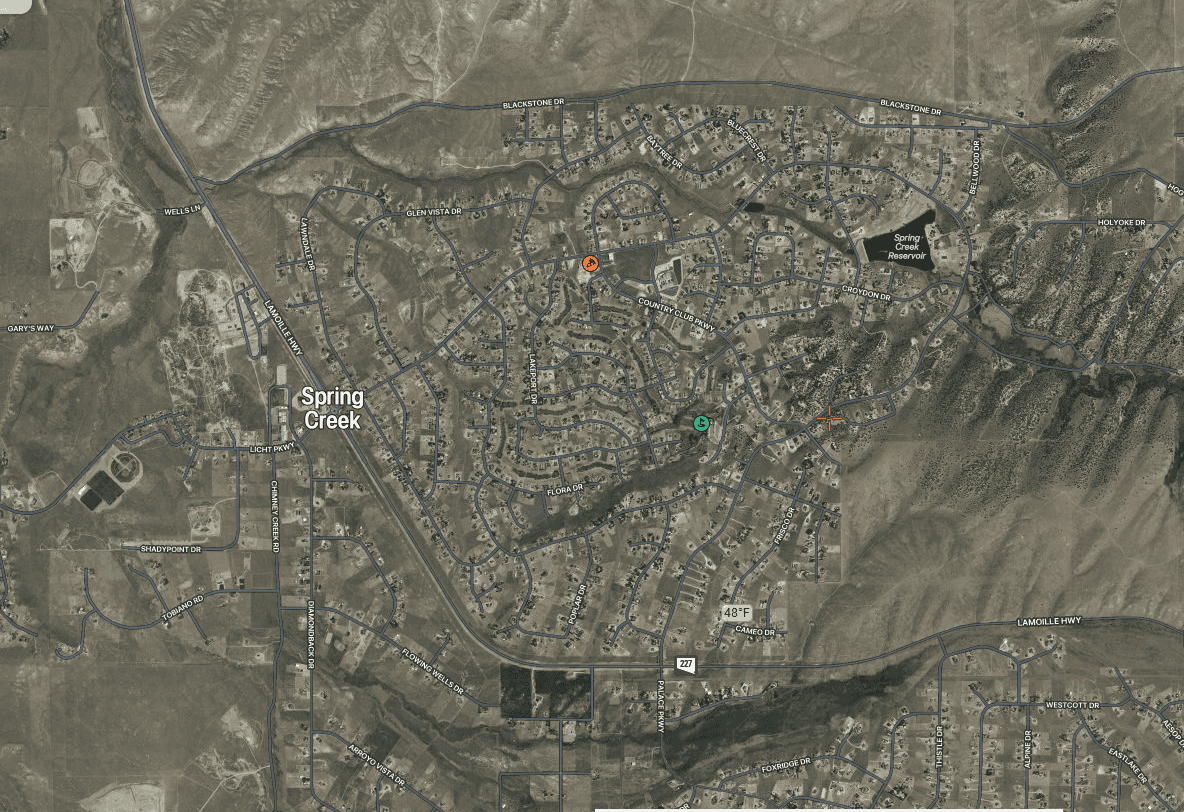

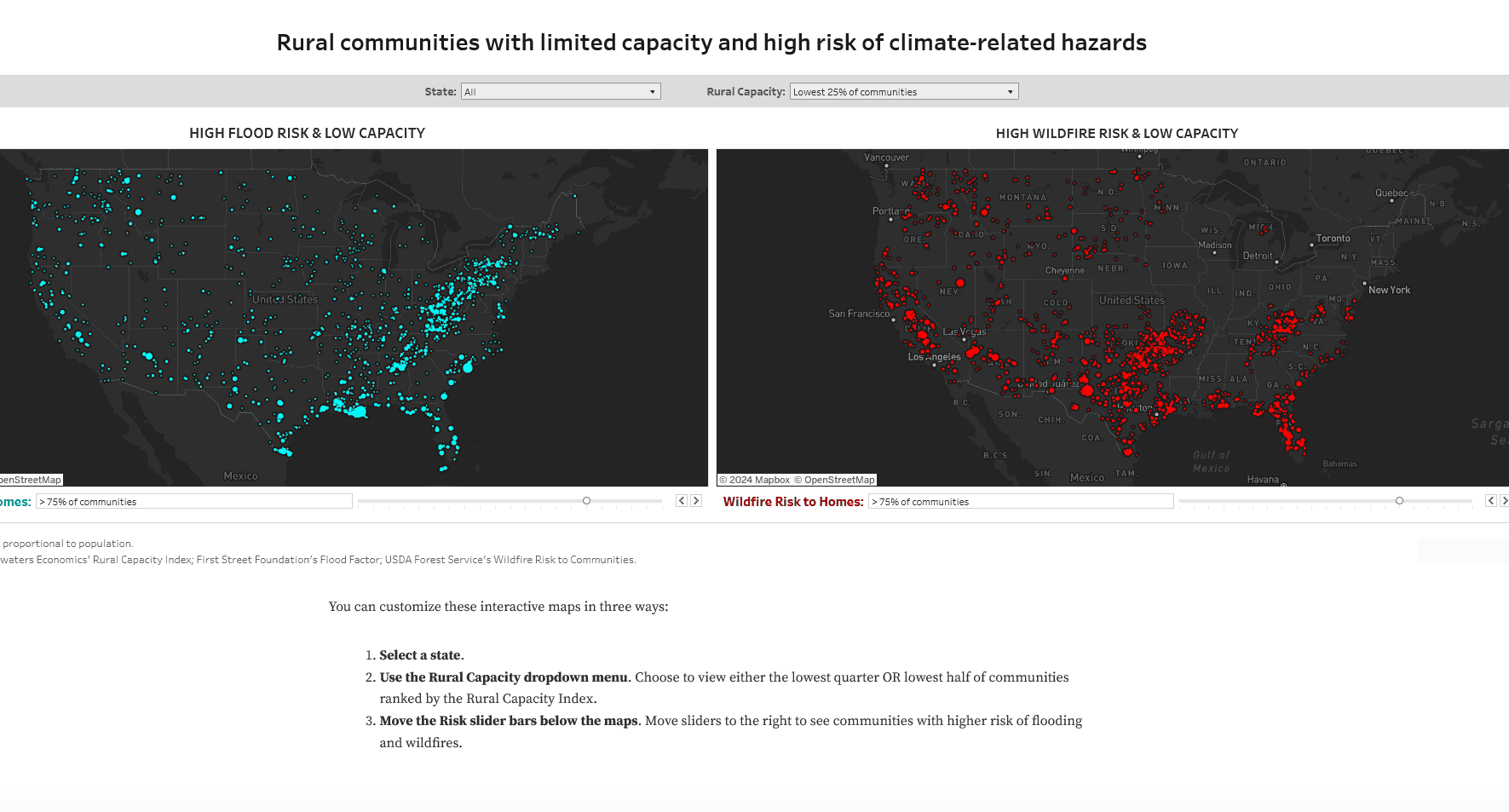

You can click on the above photo once and get a much better view. The big red blob on the Nevada wildfire map is Spring Creek Nevada.

You can click on the above photo once and get a much better view. The big red blob on the Nevada wildfire map is Spring Creek Nevada.

| Rural Capacity: | 50 out of 100 |

| 13th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 100th percentile in the U.S. |

So I wondered what the landscape looked like for an area with the 100th percentile for wildfire risk.

This is not a critique of Headwaters, as they used the Forest Service’s (and not First Street’s) Wildfire Risk to Communities map.

I think groups who develop maps think that they will be useful. But I don’t know. It seems like these maps don’t always directly address the problem at hand, in this case, “does a community have hired or volunteer folks available and knowledgeable to apply for federal grants?”. I know some communities who don’t.. even though conceivably the area is generally fairly well off. Maybe another solution would be to make the federal granting procedures easier to understand. I have friends with high capacity who find the processes of applying for grants for wildfire mitigation in their communities to be more difficult and confusing than needs be.. plus State requirements for fed bucks transferred to the State. It would be interesting for the Forest Service or someone else to commission listening sessions for communities on their tribulations in acquiring funding, coordinating different programs’ requirements, and so on. Maybe someone has.

Anyway here’s the link.

The sliders (the default is 50%) for the flood and wildfire maps are really important. Here is Moab, Utah, which we might think is fairly well-disposed in terms of economics.

| Rural Capacity: | 53 out of 100 |

| 21st percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 62nd percentile in the U.S. |

If you go up to 80% of communities, you can find a place like Pagosa Springs

| Rural Capacity: | 49 out of 100 |

| 12th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 85th percentile in the U.S. |

Or a community in my own area, Ellicott, CO

| Rural Capacity: | 53 out of 100 |

| 20th percentile in the U.S. |

| Wildfire Risk to Homes: | 85th percentile in the U.S. |

Now Ellicott is, for all practical purposes, a bedroom community for Colorado Springs in El Paso County, which is fairly well off. And county folks would be staffed to help communities apply for grants. But are they? Isn’t that the real question? Then there’s the question of what folks in Ellicott would actually do with the grant money, since it’s a grassland. Plan evacuations? Is Ellicott-only the right scale for that?

Communities need capacity—the staffing, resources, and expertise—to apply for funding, fulfill complex reporting requirements, and design, build, and maintain infrastructure projects over the long term. Many communities simply lack the staff—and the tax base to support staff—needed to apply for federal programs. Communities that put together applications are often outcompeted by higher-capacity, coastal cities. The places that lack capacity are often the places that most need infrastructure investments: places with a legacy of disinvestment including rural communities and communities of color.

Places that receive the most external funding – whether from state and federal programs or philanthropy – often have larger staff, more expertise, and deeper political influence, not necessarily greater merit. Communities that need the most assistance may be the least likely to even submit applications. For the United States to fully adapt to climate-driven threats and bolster aging infrastructure, its programs and policies must account for community capacity.

Where is capacity limited?

To help identify communities with limited capacity, Headwaters Economics created a new Rural Capacity Index. The Index is based on 12 variables that can function as proxies for community capacity. The variables incorporate metrics related to four categories of capacity: local government staff and expertise, institutional capacity, economic opportunity, and education and engagement. (Read more under Data Sources and Methods below.)

Results are available for counties, county subdivisions, communities, and tribal areas in the interactive map below. The tool displays data across the urban-to-rural continuum to illustrate the variability in community capacity across the country. The inclusion of metropolitan communities is necessary to show the comparatively lower capacity that exists in most rural communities.

Why not- call places that low on the economic scale and ask them what their barriers to applying for federal grants are? For some, being in the 100 years flood plain may not be a concern.

Anyway, their conclusions seem fairly straightforward.

Supporting communities

To achieve the infrastructure and climate adaptation goals in federal programs, funding agencies must consider community capacity. Programs may need to be structured differently and new strategies may need to be created to support under-served and historically disinvested communities.

Using the Index, community capacity can be supported in many ways:

- Provide direct funding. For communities with low Index scores, eliminate the need for competitive grants, which many lower-capacity communities lack the resources and expertise to apply for and administer. Federal and state programs can identify where the needs are greatest and allocate funding accordingly.

- Improve access to competitive grants.

- Allow funding to be used to build capacity—not just used for projects. For example, funding could be used for new staff positions and technical training to support long-term investments.

- Eliminate or reduce match requirements. City and county budgets in low-capacity communities may not have the revenue to meet matching requirements.

- Revise requirements for benefit-cost analyses. These technical reports are expensive and highly technical. They often undervalue the benefits of projects in lower-capacity and lower-income communities.

- Fund technical assistance. Administered by state or federal agencies or by nonprofit partners, technical assistance programs provide expertise in project identification, design, and implementation, as well as assistance in compiling grant proposals.

- Increase funding for multi-jurisdictional projects. Funding regional projects that leverage urban-rural partnerships can benefit low-capacity communities. This may require investment in regional institutions and organizations that can help coordinate resources and prioritize projects.

- Address root problems. Low-capacity communities are often economically dependent on farming and other natural resource sectors associated with volatile revenue. By strengthening policies that encourage economic diversification, state and federal policymakers can help communities generate predictable local revenue needed for infrastructure and adaptation.

On the other hand, rather than hiring more people to interpret ever-more complex programs, or regionalizing them out of the community’s direct authority (via “urban-rural partnerships”), how about considering simplifying requirements at the front end.