I’d like to point out to any FS leadership who read TSW that folks on the Forest wouldn’t talk to me to tell their side of the story. So they are being good employees. Problem is, if it weren’t for retirees who happen to keep up with the details (retirees like this being rare and threatened by loss of interest), we would never hear the FS side- unless there is an objection response on the same points. Maybe this would be a good application for AI.. “find the FS statements about … in the EA, response to comments and objections.” Still, I don’t think the Cone of Litigation Silence is good for public understanding, trust and support.

Anyway, here’s a link to Jack Igelman’s recent article on the issue. You can follow him on TwitX @ashevillejack. I’m not a legal person, as everyone knows, so there are some quotes from me that are off the top of my head about why these 15 acres are of concern. Conceivably with the same funding invested, the plaintiffs could buy their own 15 acres and manage it however they wanted. Maybe our friends at SELC will weigh in. Kudos to Jack for reading the EA!

The agency is obligated to manage the forest along the Whitewater River as a wild and scenic river corridor, which limits management options. However, timber harvesting is allowed to occur as long as it does not harm the river’s outstandingly remarkable values or degrade its water quality. The wild and scenic corridor extends about one quarter-mile on each side of the river.

“This timber prescription takes it backwards,” said Nicole Hayler, executive director of the Chattooga Conservancy. “The Forest Service has a track record of management activities in eligible areas to basically whittle away at the eligibility.”

Will harvesting “harm the values” or “whittle away at eligibility”? I don’t think we can judge without the prescription. (NHP is the natural heritage program.)

In the Southside Project’s final Environmental Analysis released in 2019, the Forest Service included a response to objections that the project analysis failed to analyze impacts to state natural areas.

The NHP determined that portions of the stand are dominated by white pine, an artifact of previous land use that is not naturally occurring.

According to the NHP, “It would be beneficial to remove the white pines from this stand, and then manage the area after harvest in such a way to restore the natural community” while acknowledging that some areas along the Whitewater River are in excellent condition.

The NHP did not respond to CPP’s interview request.

But if it’s good to remove the white pines, then maybe taking some more trees and getting openings for the “natural community” is a good idea. Again, it would be nice to see the prescription.

The timber harvest prescriptions for the tract “require harvesting much more than white pine,” SELC attorney Patrick Hunter said. “We can say with certainty that the NHP’s request to limit logging to white pine is not reflected in the Forest Service’s final decision.”

But did the NHP say to limit the logging to WP? What other species are there? Is taking out the WP and other species an opportunity to increase tree species diversity or wildlife habitat?

Although the lawsuit includes a relatively small parcel of land, Friedman said that the court’s ruling could establish legal precedent around the influence of new forest plans on projects initiated and authorized under prior plans.

“The same groups who didn’t want certain projects before will still not want them” after a forest plan is finalized, she said. “If they feel strongly enough about them and have the financial wherewithal, they will litigate those projects. That’s just the way it works for most of the country; it’s business as usual. “

Litigating forest restoration projects in the Forest Service’s Southern region, however, are less frequent compared to other parts of the country, such as the Northern or Pacific Southwest region. There has been just one forest restoration project litigated in the Southern region which stretches from Texas to Virginia since 2003.

Hunter told CPP this is the first time SELC has initiated litigation against the Nantahala or Pisgah National Forest.

Whether the case is settled inside or outside of court, Friedman said changing an existing agency decision may set a precedent for other projects and other national forests.

According to Hunter of the SELC, the lawsuit seeks to validate the understanding that activities occurring within the national forest must be consistent with the current forest plan.

He noted that the complaint could reinforce existing precedent citing a 2006 decision against the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee in which the court ruled that a timber harvesting and road building project must be made consistent with a revised forest management plan that went into effect after the projects’ authorization.

The legal action reflects broader concerns about balancing the need for timber harvesting to restore the ecology of the forest while preserving ecologically significant areas and underscores the complexities of managing public lands.

*************

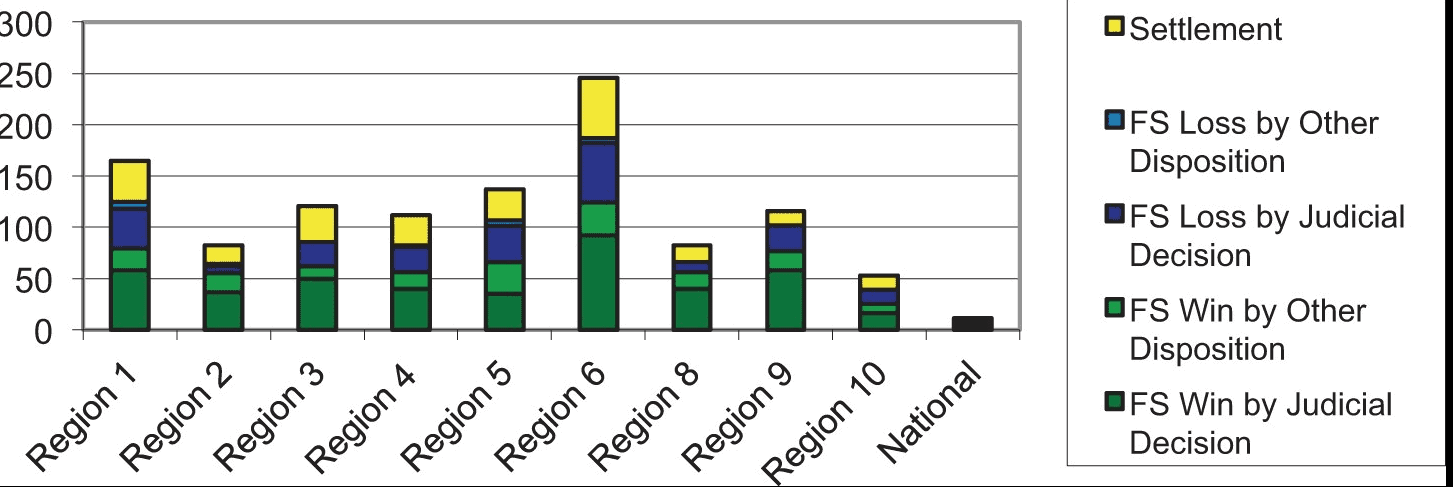

Of course, the Cherokee NF is indeed in Region 8, so I guess the difference is whether the project is a “restoration” project or a “logging” project. I would only offer that what the FS sees as a restoration project (with tree removal), other entities often see as a “logging” project. This is a real side trip- but I ran across a paper by Miner et al. from 10 years ago (no paywall) that had this graph. The authors characterized these as “land management” cases, not necessarily vegetation management cases.

*******

David Whitmire, of the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Council, which represents the interests of fishers and hunters in Western North Carolina, said the lawsuit could, however, slow down forest-restoration work.

“I would rather see money spent on projects rather than lawyers,” Whitmire said. “The Forest Service is having to back up and deal with the lawsuit. It takes away a lot of resources that would otherwise benefit the forest.”

I’d only add that if this case sets precedent for forest plans being retroactive for ongoing previously approved projects, I think it might have two effects: first that Forests will not want to do plan revisions. When I worked in Region 2, many forests were not enthused about plan revisions anyway (reopening large numbers of disagreements to what end?). Second is that if they are in revision, they would seemingly be less inclined to give areas with ongoing projects more restrictive designations. It seems that both of these co-evolutionary responses by the FS would be against what plaintiffs would ultimately prefer.

But perhaps the plaintiffs will weigh in.

“Conceivably with the same funding invested, the plaintiffs could buy their own 15 acres and manage it however they wanted.”

Sharon, you are talking sense, but you are up against a religious crusade in which facts don’t matter.

I am totally opposed to a second Trump term and would never vote for him. But as long as there’s a Democratic administration, the religious crusade will always have the upper hand in these matters.

I have to wonder if the FS had some idea that this would create a lawsuit? Were they complacent, since the article states that only one forest restoration project had been litigated in R8 since 2003? Are these 15 acres the hill they are willing to die on? Seems like pragmatism should rule the day, drop the 15-acre unit and move on. I don’t think it should have ever gotten to this point. Surely there are a lot of other issues to take on.

Well, non-FS sources tell me that SELC filed a notice of intent to sue about the NP forest plan and sued on the Cherokee in 2018.

So, we know that a) the Forest has a rationale, and b) they can’t tell us what it is due to the Litigation Cone of Silence. So we have to intuit it. Which is not great for building confidence in USG agencies, but that’s the way the system works.

Here are three possible hypotheses. 1. There are many interests collaborating and perhaps the other interests want it to go forward. Perhaps they are tired of the tactics of these groups. And I’m thinking it could be the wildlife folks maybe not timber folks. But they wouldn’t tell the public, because they want to keep good relations with these groups as much as possible.

2. Some legal angle.. if they pulled it, it would still be a kind of precedent. Which might make current plan revisions pull up. Why not see where the case goes legally before giving in?

3. A subset of 2 is possibly looking forward to the OG amendment.. whatever OG will be could also lead to litigation to stop ongoing approved projects. Much scarier than the 15 acres, at least if you live in the West and have numerous approved fuels projects.

But those are just guesses.. any other hypotheses?

I agree that there needs to be some other motivation. The cost of a lawsuit and the associated timeline just seem really hard to justify over 15 acres. They have to see this as a potential precedent that they deem as unacceptable. Maybe they just have a philosophy of “never give an inch”? Presumably, there was an objection and the Forest issued their resolution of the objection. That should be public. That might be interesting to see and may shed some light.

It’s on the project page, under the decision tab. I don’t see anything about the new forest plan but maybe I missed it.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=49747

I don’t see anything either. It seems that for the litigants to be successful in their lawsuit, they should have addressed their issue of consistency with the new Forest Plan in their objection?

Well, FWIW I don’t understand either. Maybe it’s a 2012 Rule thing?

There would be no requirement for the project to evaluate consistency with a plan that was not yet in effect, though it would have made sense to be anticipating it. I would say this means that plaintiffs could not have objected to it. See my comment below for where that determination was actually made. (This is part of what is “mystifying.”)

Jon, the complaint details all the ways we raised this issue, both before and after the plan revision was finished.

Sharon, I can’t speak for the Forest Service’s motivations. But I can tell you that this portion of the project is well outside the consensus from collaborative input, which was clearly (and spatially) given to the Forest Service before they signed the project decision.

I also am confused by the idea that the agency is “tired of the tactics of these groups.” Perhaps you mean that they agency might be tired of collaboration and tired of listening to local expert input as a way to improve projects and avoid controversy, and that it instead wants to try litigation as a way to manage public lands?

The Forest Service side of the story will be presented in the legal briefs for this lawsuit (where someone will “find the statements in the EA”).

The question of projects approved prior to a revised plan involves a part of the 2012 Planning Rule that I have always found a little mystifying (26 CFR §219.15(a)):

“(a) Application to existing authorizations and approved projects or activities. Every decision document approving a plan, plan amendment, or plan revision must state whether authorizations of occupancy and use made before the decision document may proceed unchanged. If a plan decision document does not expressly allow such occupancy and use, the permit, contract, and other authorizing instrument for the use and occupancy must be made consistent with the plan, plan amendment, or plan revision as soon as practicable, as provided in paragraph (d) of this section, subject to valid existing rights.”

The ROD for the N-P revision says, “I have not identified the need to modify any pre-existing actions involving permits, contracts, or other instruments for the use and occupancy of National Forest System lands due to inconsistencies with the revised plan.” In other words, the forest supervisor is saying that this project may proceed unchanged because it is consistent with the revised plan. Plaintiffs disagree.

Sharon, you seem to be assuming that this would be some change in the status quo making plans “retroactive.” But this has been the clear statutory rule ever since NFMA was drafted. Projects have to be implemented consistent with the plan that’s in effect.

About the idea of unintended consequences:

> first that Forests will not want to do plan revisions. . . . Second is that if they are in revision, they would seemingly be less inclined to give areas with ongoing projects more restrictive designations.

First, I wasn’t aware that Forests want to do plan revisions. I understand your point–that having to update projects to comply with new plans is an additional deterrent, but local officials aren’t the ones deciding whether to initiate plan revision in the first place.

Second, planners already gerrymander plans to accommodate incumbent projects. This case is about the opposite issue: If a Forest decides during plan revision *not* to gerrymander in its old projects, and instead to adopt more protective rules for a discrete area, can it then undermine that new direction by proceeding with a project that is inconsistent?

Sam- in my experience, it was a joint decision between the Region and the Forest as to which Forests are initiating revision. This may have changed. That would be interesting to know.

I guess that (since no one will talk to me) that the Forest and their legal advisors feel that this project does fit within the new direction. I also guess that we shall see what the courts think.

I have worked on a nearby district and while I can’t speak to the details of this particular project I can offer some general perspective on forest management in the Nantahala-Pisgah NFs. Up until a couple decades ago direction was to convert less productive native stands to white pine plantations in hopes of boosting timber productivity. This worked out well enough for producing wood but conditions in mature closed canopy WP stands are often characterized by a distinct lack of tree and understory plant diversity that differs in appearance and function from the surrounding forest ecosystem. WP naturally occurs as a minor component of the southern Appalachian landscape so removing these plantations and restoring a diversity of native trees is seen as beneficial to ecosystem health. In recent years there has been an intentional re-prioritization of restoration over timber production.

Again, not knowing anything about the stand but that it is “dominated by white pine” my guess is that the stand is slated for restoration of shortleaf pine and/or mast producing hardwoods (oak, hickory, etc) to benefit wildlife. The forest plan that this project is tied to dictates that we ought to phase out WP plantations and focus on shortleaf pine and oak restoration so I see no issue there. Interestingly the new forest plan that went into effect last year *explicitly* states that offsite WP plantations should be removed and restored to native shortleaf pine/oak so unless there is a prohibition against harvesting trees near this wild and scenic river the management direction should remain the same regardless of which plan is to be followed.

Would they moonscape the stand and destroy the scenic river view until the end of time? No.

Should they have dropped the stand to avoid litigation? Maybe.

Can they still harvest the stand by following the new forest plan? Probably.

Will this lawsuit create bigger forest plan revision headaches? I hope not.

Thanks, A., this is very helpful information.. I for one didn’t know any of this.

When what the forest plan says “should be done” (remove offsite white pine) encounters what the forest plan says “shall not be done” (standards and guidelines applicable to this location), the “shall nots” win in order to be consistent with the plan. (Consistency requirements for desired conditions and objectives are a lot looser.)

The stand is naturally regenerated and co-dominated by oaks and other hardwoods. It is not a plantation. Shortleaf pine would be off-site there. The prescription is to reduce the basal area from 140 sq ft./acre to 20 sq ft./ acre. White pine makes up approximately 40% of the basal area. Given those facts, what are your opinions?

For me, this case boils down to whether you think the Forest Service should be able to remove over 90% of the trees (in basal area) from a relatively healthy forest in a Special Interest Area and recommended Wild and Scenic River Corridor when the new and incredibly permissive forest plan dictates otherwise. The NC Heritage Program agreed that removing white pine and applying prescribed fire could benefit the oak community at the site. No one is contesting the prescribed fire, but white pine only makes up 40% of the basal area (the stand averages 140 BA, and the decision was to reduce the BA to 20 sq. ft/acre). The rest of the basal area is composed of oaks and other characteristic hardwoods. So, as they all to frequently do, the Forest Service will be removing the very species they claim to be “restoring”. Similar “restoration” in the area has done a remarkable job of removing oaks and regenerating white pine and poplar.