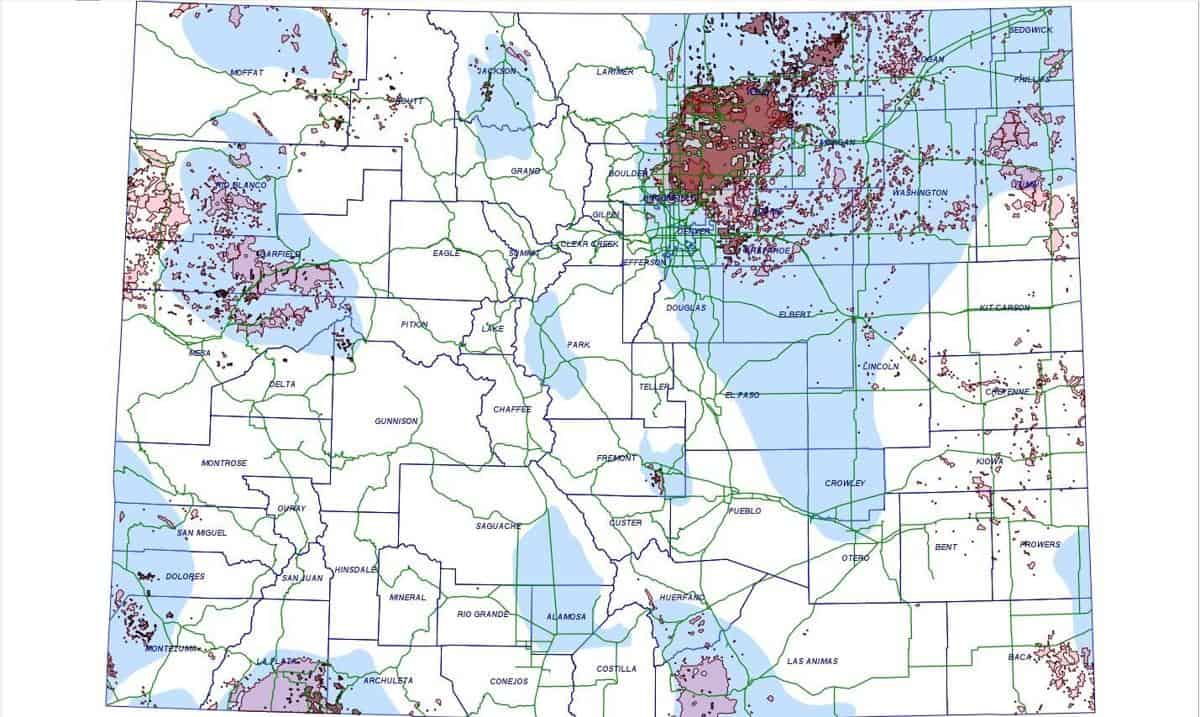

Colorado Politics had an interesting article about Colorado’s never-ending oil and gas regulation debates (they’re never-ending because some groups want to stop permitting oil and gas altogether).

Federal versus state authority

Kinder Morgan, a pipeline company, pleaded for changes around oil and gas activity on federal lands, as did the American Petroleum Institute. Among them: a claim that the state cannot veto federally-approved land use. They asked that the COGCC change a rule that makes it clear that the commission cannot deny a comprehensive area plan (which outlines an oil and gas development) located on federal-owned or managed surface lands already approved by a federal land manager. However, the COGCC could consult with the appropriate federal agency as well as the operator, according to Ana Gutierrez of Hogan Lovells, representing Kinder Morgan.

The commission should also add a rule on site-specific data, mapping and analysis on geologic hazards, such as fault lines, rock falls, mudflows and unstable slopes.

In response, Assistant Attorney General Joel Minor said relevant federal statutes dating back to 1920, as well as case law, do recognize state authority to regulate oil and gas activity on federal lands. That includes state authority to protect the environment and wildlife resources on federal lands, he said.

Is that just about oil and gas on federal lands, or does it apply to everything (mines, windfarms, etc.)? Does it only work if states want to be more protective?

Meanwhile, if you think governments in D control will be spared lawsuits about the environment..Wild Earth Guardians is suing the State of Colorado for moving too slowly towards its climate goals.

Such a plan is still months away. The state has been working with an outside consultant on a roadmap to guide its policymaking to meet the climate targets. Putnam expects the effort to wrap up by the end of September.

He added the lawsuit won’t force the state to move any faster. If anything, he worries it could divert scarce legal resources away from the rulemaking process into a legal defense. In a statement from the Governor’s Office, spokesperson Conor Cahill expanded on the point, writing the administration has taken “unprecedented action” to retire coal-fired power plants and electrify Colorado’s economy.

“It’s very unfortunate that some seek to distract from the nationally-leading success of Colorado in order to justify a risky and expensive strategy such as a state-based cap and trade system that has not demonstrated the ability to effectively cut emissions elsewhere. Coloradans trust that Governor Polis will continue to act boldly and swiftly and utilize the tools and resources available to create good green jobs, address climate change, and ensure we can all breathe cleaner air,” wrote Cahill.

Nichols countered the state doesn’t need to waste time fighting the lawsuit. All it needs to do is submit rules to put Colorado on track to meet its climate goals.

“We don’t rush into lawsuits. It’s not something we take lightly, but the stakes are so high here,” he said.

In my experience, speed has never been the ally of crafting good rules about complex phenomena with diverse stakeholders and interests.