I have often wondered why Forest Service scientists and managers talk about risk and uncertainty, yet don’t wander into the territory of “novelty, surprise, and ignorance.” My studies in decision-making and economics inform me that risk and uncertainty are the domains of games where probability distributions are well-known. Another realm, the realm of novelty, surprise, and ignorance is where many business and organizational management decisions live. That is why I’m often railing about “wicked problems”, and about how to make sense of the organizational, environmental, and social contexts we dwell in. Today I want to explore the wilds of “organizational ignorance.” In short, I want to take a look at what to do when we just don’t know.

To make my case, I want to examine a little article that I found a few years ago on the subject, titled Managing Organizational Ignorance, by Michael Zack. The only time I mentioned it before on internet chatter, best I can tell, was when the Forest Service was trying to wed Planning with Environmental Management Systems. (my Forest Service EMS/Planning blog chronicles are here). Here is what I said:

[A]s we continue on this EMS journey maybe we ought to spend more time exploring novelty, surprise and ignorance. Study adaptive management, and read in detail books like Panarchy, Supply Side Sustainability, Compass and Gyroscope, Discordant Harmonies, and more. And don’t forget to wander over and read Michael Zack’s Managing Organizational Ignorance—either right now, or later after you’ve worked yourself into a frenzy over EMS and come up short.

Zack begins with one of my favorite quotes, from Neil Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, “Ignorance is always correctable. But what shall we do if we take ignorance to be knowledge?” [Note: Postman’s book ought to be required reading for everyone in the U.S.—to better understand our current plight w/r/t ignorance]

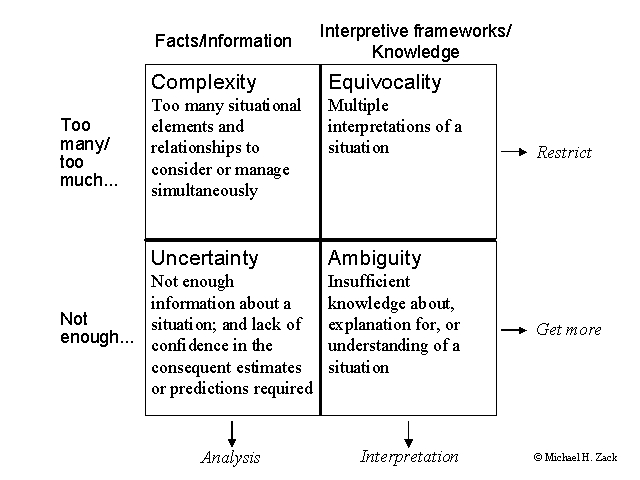

Zack builds his thesis around four knowledge-processing problems, each describing a unique form of “organizational ignorance”:

- Uncertainty: not having enough information;

- Complexity: having to process more information than you can manage or understand;

- Ambiguity: not having a conceptual framework for interpreting information;

- Equivocality: having several competing or contradictory conceptual frameworks.

Each problem describes a particular form of organizational ignorance, calling for a particular knowledge-processing capability. Each in some way also represents a fundamental organizational or strategic management problem. Taken together they define the range of knowledge processing capabilities an organization must have to manage its ignorance effectively. These four knowledge problems can be categorized along two axes: 1) the nature of the knowledge being processed, and 2) whether the solution is to acquire more knowledge or to place restrictions on what you have.

Here is Zack’s table, summarizing the relationship between the knowledge problems and information processing (gathering, restricting, analyzing, etc.):

Zack sums up with:

The four knowledge-problems framework provides a powerful lens for viewing information processing, communication, and knowledge management in organizations. It suggests several prescriptions and conclusions.

- Organizations must be open to novelty and anomaly. Only by acknowledging its ignorance can an organization put itself on the road to learning. Organizations must recognize and accept that there are events that may be difficult to explain because no one understands them well enough. …

- Knowledge management today focuses primarily on solving problems of complexity and uncertainty. It aims to share and exploit what is known within well-defined circumstances and contexts, and is dominated by information technology. Expert systems apply codifiable but highly complex sets of rules; best practice databases attempt to share less structured but well-documented expertise; point of sale systems attempt to provide rapid feedback for managing market uncertainty, while e-mail and discussion databases do the same for internal uncertainty. Much less effort has been spent worrying about the ambiguous and equivocal situations resulting from more profound forms of organizational ignorance. To truly manage knowledge and expertise, however, organizations must make sure that their members work toward building a shared fundamental understanding of the situations and problems they face. Meetings and teams, as well as informal opportunities for engaging in sense-making conversations that raise good questions, challenge the status quo, and directly deal with ambiguity and equivocality are all essential. Solving convergent, well-defined problems requires having a shared understanding in place first. It is therefore critical for organizations to be aware of and to solve problems of ambiguity and equivocality before diving into the more structured problems of uncertainty and complexity.

- Information technology can play an important role in managing information and knowledge, when it is appropriately applied. This requires diagnosing the nature of the knowledge problem beings solved. Information technology makes sense in cases of uncertainty and complexity, but much less so for dealing with ambiguity and equivocality

- Organizations need to go beyond their own boundaries to find the knowledge they need to help them make sense of the world. Where the organization is relatively ignorant…, it should include [constituents] in the sense-making process. In doing so, the organization will also develop a shared understanding and basis for ongoing communication with its [constituents]. As ambiguity and equivocality give way to uncertainty and complexity, the organization can more easily migrate to more structured technologies to communicate and coordinate with its external partners. … Organizations may use information technology to exchange data and information, but they will need to use social interaction to exchange knowledge in building a shared understanding about their commercial relationships.

- Senior executives and managers must interact freely with those at lower levels of the organization in sensemaking and problem-solving processes to discover what the organization as a whole truly knows. It is not enough for managers merely to catalog organizational knowledge by creating a “knowledge map.” Rather, they must sense the organization’s knowledge and ignorance by engaging all organizational levels in the process of resolving the four knowledge problems.

- Like managing knowledge, managing organizational ignorance requires an appropriate culture. In general, the organization must create an environment in which it is acceptable to publicly admit that one does not know something. Multinational organizations I have observed find this to be particularly problematic in certain national cultures. Managing complexity requires a culture in which it is acceptable to identify and support experts and seek their advice. Resolving uncertainty requires a culture supportive of open, clear and extensive cross-boundary communication, and a willingness and ability to bridge various languages (both professional and national) in use across the organization. Resolving ambiguity requires the ability to confess ignorance and confusion. Managing equivocality requires an environment in which it is acceptable to disagree about interpretations and which accepts diversity of views as well as useful and productive consensus.

- Each of the four knowledge problems suggests a different set of processes, roles, information technologies, and organizational structures for their resolution. … Often … problems are intertwined. [An organization] must be flexible enough to modify itself dynamically to deal with the knowledge problem at hand. …

- Even the non-routine or unpredictable aspects of the four problems can be managed, or at least anticipated, in a routine fashion. Where ambiguity or equivocality routinely arises, organizations should create standing mechanisms to address them. Provisions must be made for face-to-face conversations to occur among those most relevant to resolving ambiguity or equivocality. Those responsible for executing the resulting interpretations must also be involved so that those interpretations can be meaningfully communicated. Uncertainty can be routinely handled by anticipatory mechanisms for exchanging information; complexity can be handled by anticipatory mechanisms for locating knowledge.

- The four problems suggest a framework for managing organizational learning. Ambiguous and equivocal problems often represent non-routine events about which the organization lacks sufficient knowledge. The process of resolving ambiguity and equivocality, however, is the stuff of which organizational learning is made. Ambiguous and equivocal events, if encountered enough times, eventually become familiar enough to be migrated to more routine processes. Organizations must have the ability to evaluate events to determine if they are interpretable or not, route them to the appropriate resolution process, and eventually migrate those that become familiar to routine processes, thereby reserving the organization’s capacity to continually handle novelty and confusion. [Emphasis (bold) added by Iverson]

Is the Forest Service ready to deal with Zack’s four knowledge-processing problems? Do they help make better sense of “ignorance problems” than traditional rhetoric of “risk and uncertainty”? Have Forest Service managers/scientists/staffers already been dealing with these problems albeit in different frames? In short, what do you think?