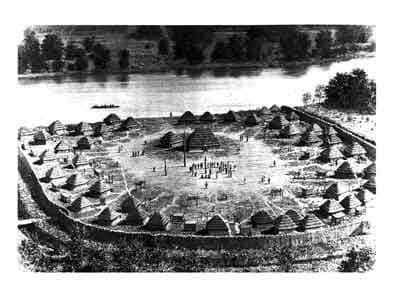

Sketch of Cherokee Village Historic painting of a Native American village in the Southeastern United States

Painting by Lloyd Kenneth Townsend

In responding to a comment by Jim Furnish, I found this fascinating paper on the fire history of the southern US and Native American burning. Quite a bit of interesting info. I had no idea that bison migrated into the area after 1500.. I actually didn’t know bison had been there at all.

Some historical texts mention fire without commenting on the purpose or whether it was intentionally set or not.

White (1600, cited in Russell 1983), for example, saw from his ship rising smoke, when he was searching for the colony on Roanoke. Others describe habitats that may have been fire-maintained including large treeless zones, canebrakes, park-like forests, and pastures occupied by grazing bison. The fact that fallow fields grew into forests within decades after Indians abandoned an area (Day 1953; Maxwell 1910) and Indians’ lack of metal tools to clear forests (Bass 2002) support the proposition that Native Americans used fire to clear forests. Vast open areas or grasslands in western Virginia and along the Virginia-North Carolina line were described by Beverly (1947) and Lederer (1891, cited in Maxwell 1910), who traveled through different parts of Virginia in 1669 and 1670. In 1705, Beverly (1947) described the hundreds of acres of grasslands on the Virginia Piedmont.

In the 1720s Mark Catesby noted that in the Carolinas there were large meadows with overgrown grass (Barden 1997). In Ashley County, Arkansas survey records from the General Land Office note the presence of grasslands (Bragg 2003). Several sources, including George Washington’s writings from 1752 (Brown 2000), mention large grassy areas in the Shenandoah Valley and conclude that Indians used fire (Fallam 1998; Fontaine 1998; Maxwell 1910). The presence of the bison in the Southeast provides indirect evidence of wide-spread grassland resulting from Indian burning practices. The bison migrated into the region sometime after 1500 AD. Their eastward movement was probably a combination of the open areas created by anthropogenic burning and the lack of predation after the decrease of the Indian population through European diseases (DeVivo 1991; Bass 2002).

……..

The exclusion of fires from southern landscapes caused changes in vegetation. When fires became less common, forests began to regenerate or the composition of existing forests began to change. The Appalachian hardwood forests recovered in the almost complete absence of fire, which had detrimental effects on fire-tolerant oak and fire-dependent pine stands (Brose et al. 2001a). The establishment of oaks (Q. rubra, Q. alba) had formerly been facilitated by Native American fire—possibly over thousands of years—and by logging, burning and the chestnut blight from the time of European settlement until the beginning of the 20th century.

However, during the time of fire suppression these sites have been invaded by late-succession species. Abrams et al. (1995) studied an old growth white pine (P. strobus) and mixed oak

community in southern West Virginia and came to the conclusion that fire and other fairly frequent disturbances maintained this forest over the past 300 years. After the exclusion

of fire, oak recruitment ceased in favor of maple (mainly Acer rubrum), beech (Fagus grandifolia) and hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). Today, sites that have been cut over since 1930

are often dominated by maples (Acer rubrum, A. saccharum), yellow poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) and hickories (Carya spp.). Only on drier or nutrient-poor sites do oaks still regen-

erate successfully (Lorimer 1993).

************

And from Norm Christensen at Duke.

Analysis of soil charcoal samples demonstrated that fires became more frequent about 1,000 years ago. This coincides with the appearance of Mississippian Tradition Native Americans, who used fire to clear underbrush and improve habitat for hunting, Christensen said.

Fires became less frequent at the site about 250 years ago, following the demise of the Mississippian people and the arrival of European settlers, whose preferred tools for clearing land were the axe and saw, rather than the use of fire. Active fire suppression policies and increased landscape fragmentation during the last 75 years have further reduced fire frequency in the region, a trend reflected in the analysis of samples from the study site.

The relative absence of fire over the past 250 years has altered forest composition and structure significantly, Christensen said.

“The vegetation we see today in the region is very different from what was there thousands or even hundreds of years ago,” he noted. “Early explorers and settlers often described well-spaced woodlands with open grassy understories indicative of high-frequency, low-intensity fires, and a prevalence of fire-adapted species like oak, hickory and chestnut, with pitch pines and other (low-moisture) species on ridgetops. Today, it’s become more mesic – we find more species typical of moist ecosystems. They’ve moved out of the lower-elevation streamsides and coves, up the hillsides and onto the ridges.”

Aside from any inherent historic and scientific interest, knowing more about pre-settlement fire regimes in the region may help forest managers today understand the likely responses of species to the increased use of prescribed fire for understory fuel management, Christensen said.

However, he cautioned that because of widespread changes that have occurred in the forests as a result of centuries of fire suppression and other human activities, as well as climatic changes, “prescribed burns may or may not behave similarly to fires that occurred in the past. Fires today likely would burn hotter and more intensely than fires did in the past.

“Also, although history tells us what could be restored, it doesn’t tell us what should be restored,” he added. “That depends on which species, habitats and ecosystem services we wish to conserve.“

******************

I so agree with Norm’s last sentence.

I’ve read this two or three times and wanted to respond, but how? Do we really know the combination of drivers that contributed to past ecological conditions? Seems Archaeologists have a different take on why early cultures acted one way or another. Yes, they used fire, but there was more at work!

I am intrigued by the woods Buffalo of the South, back in the day. I always assumed that species had actually evolved to adapt to conditions in the South. Dioramas, at one of our State Parks, depict Native Americans hunting Mastodons in a treeless environment. Nowadays, you can’t find a place there that doesn’t have climax oak/hickory. Did fire, or lack thereof, cause that? Doubtful.

Spruces used to grow in Mississippi, did fire cause that? Doubtful, a changing climate (natural) from the last ice age most likely is that cause!

Being a son of the South, we are born with a drip torch in our hand. Some areas have had Rx burn intervals of no more than six years, for forty years. However, if we miss one burn cycle, it takes mechanical prep prior to engaging fire again, or we lose the stand to “too hot” conditions.

I would tend to direct folks to Thomas Nuttall’s book, written about his journey to Arkansas, following the New Madrid Quakes of 1812, for another perspective…..

Still, very interesting take, and one more piece of the puzzle that was our past!

Clearly a changing climate coming out of the Pliestocene, combined with arrival of Asians, and presence and then loss of mega-fauna, muddle the early picture as does what natives did pre-Columbus and post-Columbus till the Revolutionary War days. If we want oak in the Appalachians to remain, longleaf pine/red cockaded woodpeckers, and quail in the Deep South, switch cane in eastern North Carolina, etc., clearly fire is a tool we must embrace with enthusiasm (which I would like). But philosophically, if you ask the question “is fire natural”, north of I-10 in Florida and east of the Oklahoma line, it would have been scarce as hen’s teeth sans anthropogenic ignition. Sure, the occasional stand-replacing big fire every 500 years (maybe less in the Pocosins)…. but the reality is that lighting ignitions north of Florida, just don’t occur. A maple-beech-magnolia forest in the Deep South would suck for most wildlife except neotropical migratory songbirds, but that would be “natural”. Maple is taking over everywhere and red spruce is going down, not upslope in West Virginia because that human fire regime has been broken.

It all boils down to what we want and what can be done realistically. The real answer is not much. The GWJEFF can burn about 20,000 acres out of 1 million a year which nowhere approaches Frost’s and Abram’s 3-7 year fire return interval for xeric or mid-SI oak forests. No way to have landscape fires on the Atlantic coast to create the habitat extent whereby it matters. Outside of the quail plantations in Georgia and Florida, nobody from there to New Jersey can piece enough land together to have viable and huntable quail anymore. Maybe it is all a ginormous waste of time and we should concentrate on forests for wood, water and carbon capture. Of course the greenies in the Appalachians don’t like prescribed burning, nor do the second home Yankee types, so maybe we should keep at it?

Following from that last sentence … the laws we have today (ESA, NFMA) basically say “keep all the pieces.” (Ecological integrity/NRV is part of doing that for national forests.) The process requirements (NEPA) basically say to look at the “do nothing” option before deciding what we WANT to do that would still keep all the pieces. The “do nothing” option should be what would happen without active management, given today’s expected climate and risks created by human society. In this context, and within these limits, fuel reduction or grassland creation are things we might want to do.

I don’t agree that NFMA says “keep all the pieces”; perhaps the 2012 Rule does but that’s for lawyers to ultimately decide.

Does the Rule ever define “ecological integrity”?

36 CFR §219.19 Definitions

“Ecological integrity. The quality or

condition of an ecosystem when its

dominant ecological characteristics (for

example, composition, structure,

function, connectivity, and species

composition and diversity) occur within

the natural range of variation and can

withstand and recover from most

perturbations imposed by natural

environmental dynamics or human

influence.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5362538.pdf

Under your peculiar bifurcation of the law and its regulations, there are also very few NEPA requirements.

I am paraphrasing both laws. The diversity requirement of NFMA, which requires providing for viable populations of all species, is a higher bar on the same scale as ESA’s jeopardy prohibitions.

Well, from southern to northern Appalachians, fire risk will be going down not up as shade-tolerant mesophication continues unabated shifting the forest to maple-dominated (wet damp litter that fire-proofs a forest). And most projections show the area really increasing in precipitation. It very well could be that prescribed burning will become almost impossible to pull off and saving the fire-obligate species such as table mountain pine, pine snakes, various neotropicals will be a fool’s errand for later generations in USFS.

Hi RSB, aren’t there soil types and/or ridgetops where maples don’t do so well?

There are some edaphic conditions, SW aspect with extremely rock soils (if any soil), elevations 3000-4000 ft where even red maple gives up the ghost, but usually sans fire, you see the pine simply be replaced by ericaceous shrubs. But in the big scheme of things, without fire, yellow pine types will be on their way out from north Georgia to the PA/NY line. Every now and then, there will be pretty low site index but with enough soil where chestnut oak and scarlet oak can hang on and regenerate without fire. The pines less so….

Thanks!

Returning to Sharon’s premise for looking at this issue, what can I say being from IOWA? 500 years ago if you walked from the Miss. River to the Atlantic, one could take several routes, northern to southern. I realize each would yield very different experiences, and I should have specified I was referring to more northerly routes when stating the hiker would be in mature/old growth forest most of the way. Yes, the South is different, notably with extensive loss of longleaf pine ecosystem.

Jim: What is your source of information that someone taking the route you have outlined “would be in mature/old growth forest most of the way?” Based on what evidence? Why are some of your hypothetical trees only mature, and not old-growth? No prairies or meadows? Seedlings or saplings? Your time would be 1520 or so (“500 years ago”), and I am uncertain how you are familiar with forest conditions at that time. What Tribes lived along this route at that time, for example? And how did they survive in an old-growth forest? This sounds like biased speculation and I would like to be proven wrong.