I’m curious about gentrification, and whether residents of an area (Native or not) should some kind of right to continue to live there, given that it has become an area where young people are priced out of housing and costs of living. You can think of say, Jackson in Wyoming. I don’t know the answer, but I’m raising it as a question. And would current natives have more of a right than new migrant low income people with jobs there?

We have our own Jacksons, Vails, and so on in the US, sometimes near federal lands, and the amenity migration plus tourism has been spreading post-Covid. Here’s one of many articles on that in Montana.

The Hawaiians have their own (at least Native Hawaiians according to this WaPo article)

The displacement of Native Hawaiians is a particularly acute concern now, as much of the island has been targeted for gentrification, driving up the costs of living and forcing many Native Hawaiians to move to mainland cities like Las Vegas.

And the short-term rental phenomena and displacement also occurs in England, as per this BBC story.

In nearby Bruton, the chair of the town council, Ewan Jones said the rise of holiday lets had taken many rental properties out of the market.

“We have the UK’s biggest farmhouse cheese manufacturer in this parish, you talk to them and their number one concern is ‘where do our workers live?'”

He said schools in particular were worried about the supply of homes their teachers and support staff could afford to live in.

This statement could be about Durango or any number of communities in the US… it’s just interesting this seems to be a common trend across many countries (at least those whose news is in English).

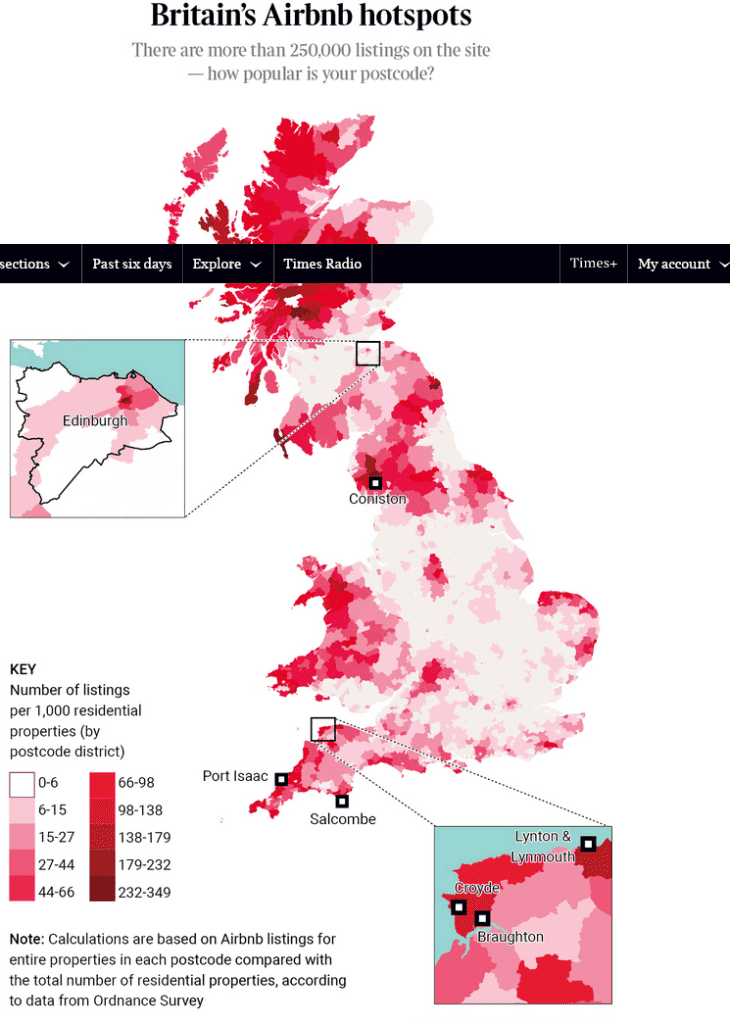

After I read this excellent article in the The Times Sunday Magazine, I went down a curiosity rabbit-hole on Airbnb and influences on housing availability. The Times has a six month deal for one pound. Seems like this would be a great interactive map and story for the US.. I wonder if someone’s done it?

From the story..

Devon locals complaining about how Devon locals are being priced out of Devon — so far, so unsurprising. But in the past few years the focus of complaint has changed. The main threat used to be second home owners. In 2011 local councillors formed a steering committee to promote affordable housing and local jobs; their charter firmly stated that stemming the tide of second homes was a priority. But now that threat has been overshadowed by a new and more virulent one. The area has seen a huge, Silicon Valley-charged influx of Airbnbs. Of the 1,022 residential properties in Lynton’s EX35 postcode, 163 of them are available for short-term rental on Airbnb. That’s almost one in six properties, making it one of the most Airbnb’d places in the UK. But not the most.

Airbnb was originally presented as a pocket-money booster for people with a spare room — the company’s pitch to investors in 2008 was “book rooms with locals, rather than hotels”. But data compiled exclusively for The Sunday Times Magazine illustrates just how pervasive Airbnb has become in many of Britain’s most popular tourist areas. That the demand for holiday homes should be higher in these areas is to be expected, but the scale of the shift to short-term lets — and the knock-on effect this is having on villages, towns and cities and the people who try to live in them — is dramatic.

Here’s an article about how it works in Australia, with some interesting ideas..

Given holiday homes will remain an important part of tourism infrastructure in regional areas, could we make use of them in more strategic ways? For instance, during natural disasters or housing crises?

An estimated 65,000 people were temporarily displaced during the 2019-20 bushfires that ravaged the east coast. Some 3,100 houses were also destroyed, leaving around 8,000 people in urgent need of accommodation.

Similarly, over 14,000 homes were damaged in NSW by last year’s floods, and more than 5,000 were left uninhabitable.

A year later, many people in NSW continue to live in inadequate accommodation. Government-issued temporary homes, such as campervans and “pods”, are in woefully short supply.

Housing generally takes a long time to build, making it difficult to respond to such short-term increases in demand.

More strategic and creative use of the short-term rental stock might be the answer. We have seen some gestures by Airbnb and other platforms to support people displaced by disasters, but these responses have largely been ad hoc and uncoordinated.

When disaster zones are declared, Commonwealth and state governments could mandate and coordinate access to short-term rental accommodations for displaced residents and relief workers.

We could even extend such declarations during housing crises like the one we’re experiencing now, as the mayor of Eurobodalla on the NSW south coast has suggested. This would give governments time to deliver longer-term housing solutions in areas of heavy demand.