Thanks to Jon for another excellent litigation round-up on Friday!

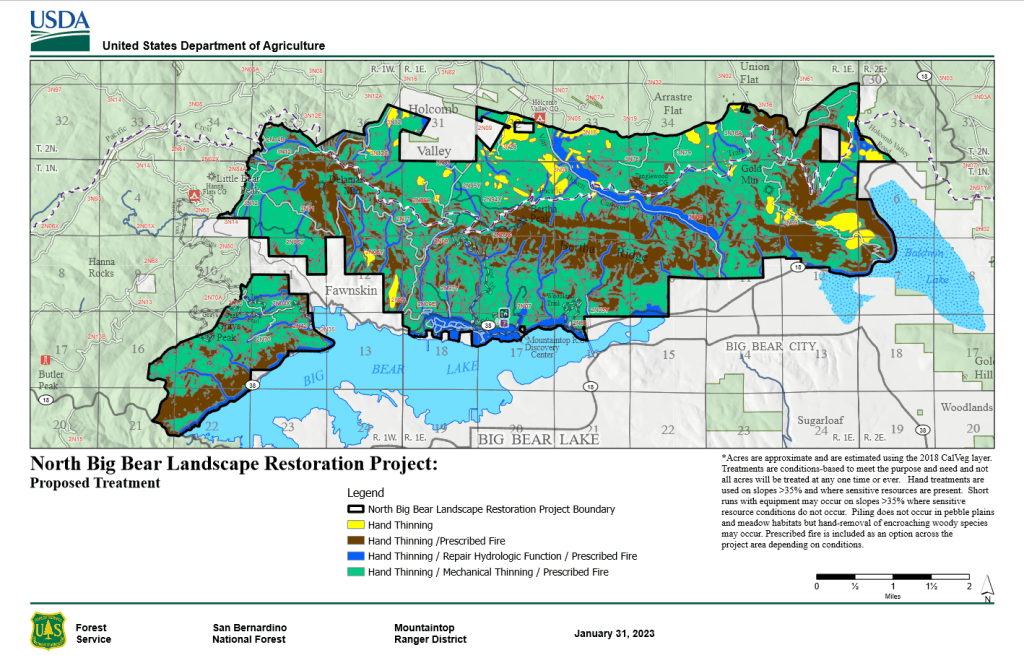

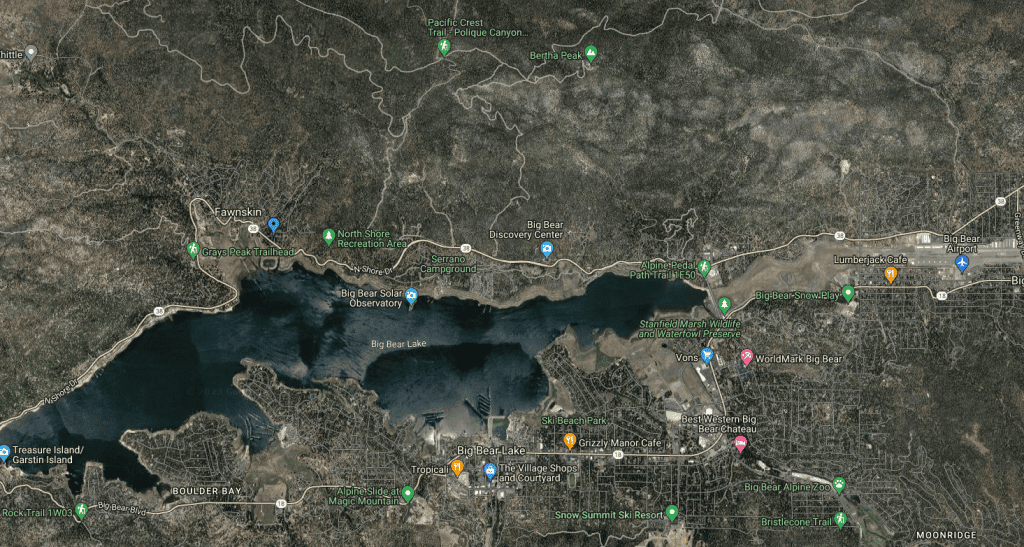

Both Larry and I are familiar with the San Bernardino National Forest. Both of us were dubious as to Hanson’s claim this project involves fuel treatment “in the remote wildlands” . So I looked up a map for the project.

From this map, you can see the miles from the project to WUI areas. But if you aren’t aware of the built environment around Big Bear Lake, here is a Google map

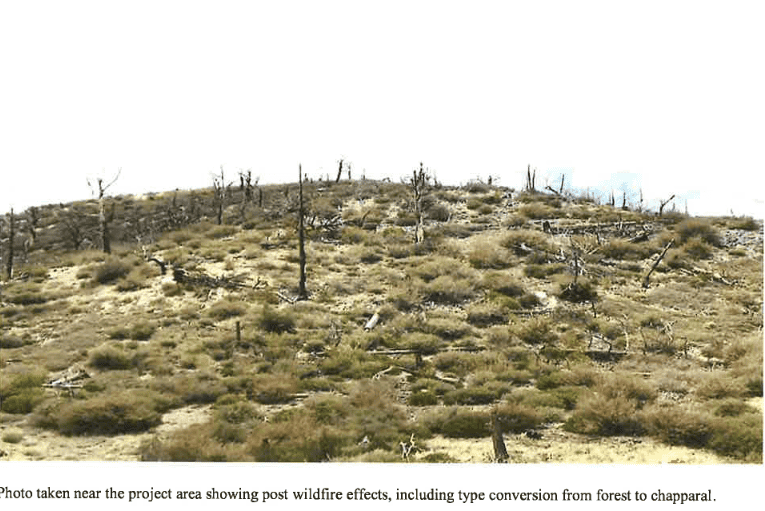

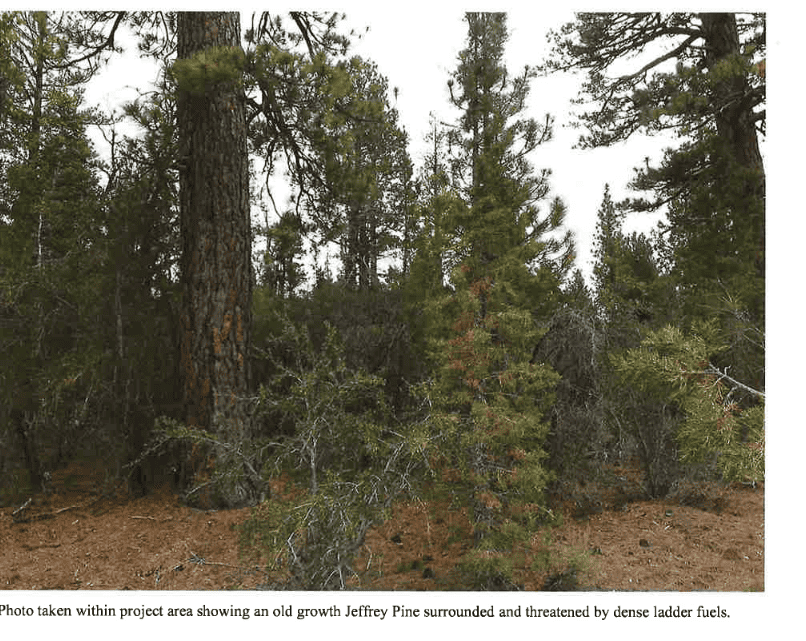

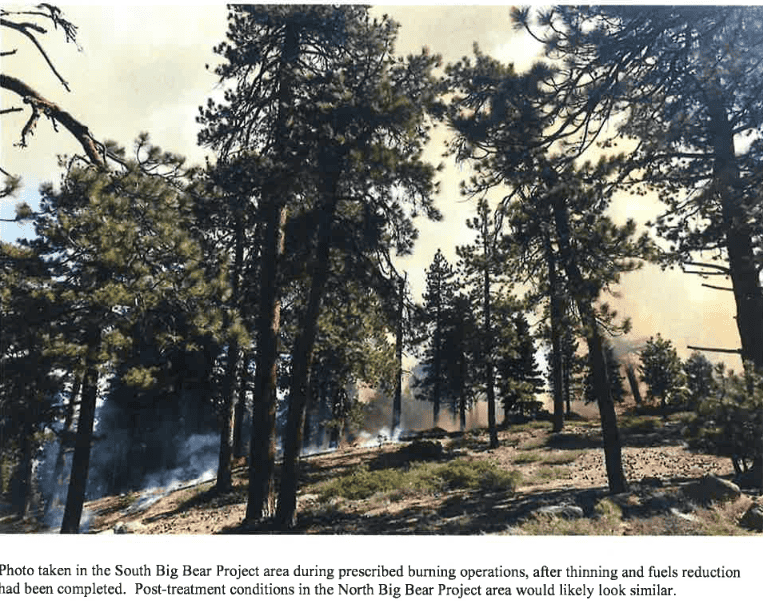

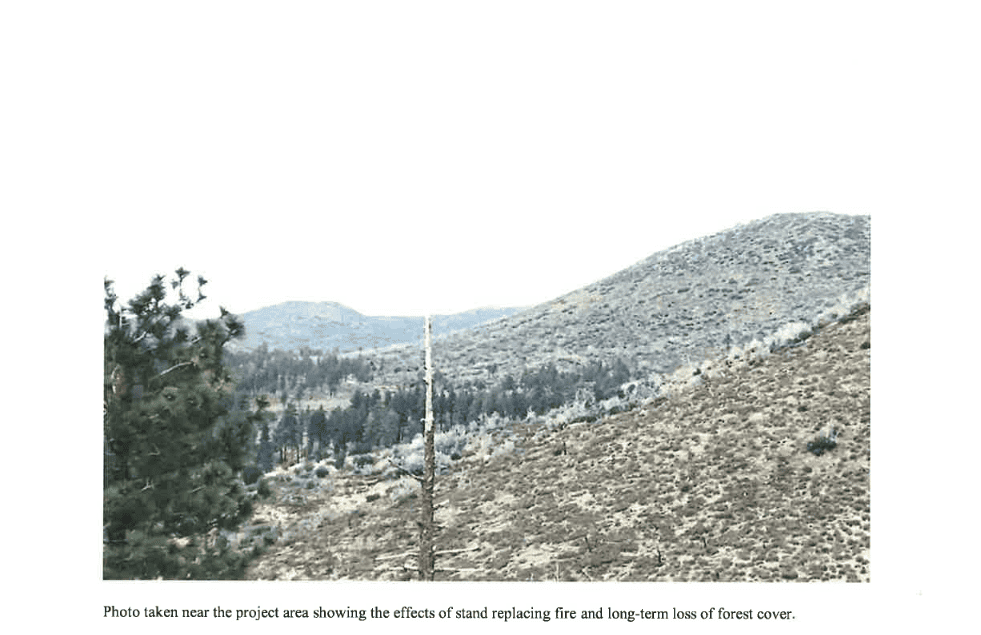

The Decision Notice had some nice descriptive photos, so here they are:

When I’m working on MOG and hear “leaving things alone is best for carbon” I think of places near my house that look something like the next two photos.

Personally, I’d like Mr/Ms Old Growth Jeffrey to survive a fire.

Personally, I’d like Mr/Ms Old Growth Jeffrey to survive a fire.

The project’s around 12K acres of treatment and has a 49 page EA. The separate response to comments is 21 pages; it has many specific answers to various scientific studies submitted in the comments. This project also has its own fairly extensive monitoring plan.

Here’s what Hanson says in an LA TV news story.

According to the lawsuit, the last time the San Bernardino National Forest conducted a similar restoration project was in the early 2000s, prior to the devastating Grass Valley Fire of 2007 that burned 199 homes.

Hanson said such an approach makes homeowners in the wildlands subject to even greater fire risk. He said the Forest Service should instead focus on making 100-foot perimeters of defensible space around homes in the forest.

“When they remove a lot of trees it actually makes the fire burn faster through those areas, and that often times is toward towns,” Hanson said.

I think this is something different from usual, a bit of an escalation, from “fuel treatments don’t work” to “sure less fuels mean big trees don’t die, but the fire itself can move along the ground faster and go toward towns.” That’s not fire suppression folks’ experience but…the FS couldn’t speak to reporters due to litigation. So the reporter had to poke through the documents. Which is kind of a painful way to get info for someone on the clock.

Seems like we as a community (at least those of us who support fuel treatments) should be able to do better in terms of being able to talk to reporters. In the old timber wars days, reporters could always call AFRC- but when there’s no timber, now there’s no one for reporters to call. Perhaps something to work on. People Living With Wildfire? Wildfire Adaptation Network?.. Conservationists for Wildfire Adaptation? No, it needs a good acronym.

Reporters could seek input from the Society of American Foresters, which has detailed position statements on:

* Forest Management, Carbon, and Climate Change

* Wildland Fire Management

* Use of Prescribed Fire in Forest Management

https://www.eforester.org/Main/Advocacy_and_Outreach/Position_Statements/Main/Issues_and_Advocacy/Position-Statements.aspx?hkey=7462747e-74fb-4ecd-8542-e089fdae5b8f

And the California Society of American Foresters:

* Forestry Solutions to California’s Wildfire Crisis

* The Role of Mechanical Treatments in Reducing Risks of Catastrophic Wildfire in California

https://californiasaf.org/policy/

Reporters would still need the name of a particular expert to speak with.

I would think that it would (or should) be a fuels project, with a small volume timber sale embedded. I really doubt there would be much saw timber to thin out, except in isolated pockets.

Here is where I worked on a fire salvage sale, 20 years ago. All the wildlife snags are gone. Some of my skid trails are still visible. Some are not.

https://www.google.com/maps/@34.3192313,-117.0063359,1214m/data=!3m1!1e3?authuser=0&entry=ttu

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fsbdev3_045471.pdf

I guess this wasn’t worth the time to read by those suing, or they didn’t appreciate non-agenda driven science?

Not to mention not appreciating thinning and Rx that moderated the Cranston Fire (2018) at the edge of Idyllwild and El Dorado Fire (2020) as it approached Angelus Oaks.

What’s interesting about court cases is that folks on either side can claim anything. Judges have discretion as to how deeply they wade into the arguments pro and cons. I just wish reporters had a chance to hear from the other side (like the document you linked) and not just report “he said this” “the FS couldn’t respond.”

LOL. Those “remote wildlands” are chock full of tourists all summer long dispersed camping next to their cars.

I didn’t know the SB allowed dispersed camping!

Like many National Forests in destination areas or near large metro areas, “Rules” and “Allowed” are two very different items. Many activities against the rules are “Allowed” through a lack of enforcement, which links back to the previous post not too long ago about Law Enforcement Officers per acre.

In the past, I know they allowed “plinking” at selected shooting sites, which are tagged on Google Maps.

If you have a keen eye, you might have noticed the mountain mahogany in the forested picture. It burns hotter than most trees, with very dense wood. There are also interesting rain-shadow effects in those mountains. Some areas have fir and lodgepole, while others have brush and pines. They also get high winds, similar to the ‘Santa Ana’ winds, below. Instead, they call it an “inside slider”, where a dry storm comes from the northeast, with very little moisture, along with dry high-velocity winds. That can push fire into the project area, possibly spotting across the lake.

Anon, the front range kinds of forests have more people recreating, but distant areas also have less likelihood of seeing anyone of the LE persuasion so might also lead to misbehavior(like bike tracks into Wilderness), although fewer people misbehaving. I wonder if there’s a study somewhere that looked at “where people follow the rules and don’t given the low LEO/acre”. Seems like that would be very useful to know to focus limited resources.

Sharon said: “When I’m working on MOG and hear “leaving things alone is best for carbon” I think of places near my house that look something like the next two photos.” [The photos show fire driven type conversions]

This is revealing, because type conversion is an unlikely event. It is much more likely that fire burns in a mixed severity pattern, and does not cause type-converson. It’s irrational to jump to improbable outcomes when thinking of fire and carbon.

Some things to consider.

Conversion to non-forest is highly speculative. We might be able to predict where it is more likely to occur (conversion-vulnerable sites) , but we can’t confidently predict specifically where it will occur, because type-conversion is disturbance driven and the location, timing and severity of disturbance is highly unpredictable,

Our ability to avoid type conversion by logging is quite limited. Even thinned forests can experience stand replacing fire when it’s hot, dry, and windy.

There is only a small spatial overlap between fuel treatments and wildfire, so, the amount of carbon emitted from thinning vastly exceeds the carbon that might be saved by avoiding type conversion.

When type-conversion is a concern, efforts are better spent carefully choosing whether and what to replant after it burns, and maybe doing non-commercial thinning of the smallest fuels and conducting prescribed fire before vulnerable sites burn in a severe wildfire.

And don’t forget type-conversion is a form of climate adaptation that maybe we should not interfere in. We need to appreciate severe fire when it clears a less-adapted vegetation type to make way for a different vegetation type more adapted to the future climate. (Cheat grass is not an example of this, but forest to chaparral arguably is).

Your assumptions are based on pre-human landscapes. Yep, if only we had left all forests alone, for hundreds of years, fires wouldn’t be so damaging. You might want to join us, in this new millennium. We have lots of work to do.