This is a guest post by Sarah Hyden.

The Indios Fire in the Jemez Mountains of the Santa Fe National Forest Photo: US Forest Service

The Indios Fire in the Jemez Mountains of the Santa Fe National Forest Photo: US Forest Service

At midday on May 19th, Santa Fe National Forest (SFNF) fire managers were notified of a new wildfire start within the Chama River Canyon Wilderness on the Coyote Ranger District, northwest of the traditional rural village of Coyote. The cause of the fire ignition was a lightning strike.

By the next day, the fire had grown to approximately 150-200 acres and was named the Indios Fire. It spread primarily to the northeast over the next three days, burning along the boundary of the wilderness, with no imminent threats to people or property. The fire was burning in dry forest, and in the midst of a strong wind pattern.

A May 20th SFNF press release about the fire quoted Forest Supervisor Shaun Sanchez as stating, “Wildfires have the potential to decrease fuels and increase the health and resilience of forests. Fire is a natural and frequent component of the ecosystem in the area, and our team will look for opportunities to restore forest health when conditions permit.”

It seems apparent that the Forest Service took the opportunity to ignite much of the Indios Fire themselves for “resource management objectives,” based on #firemappers satellite thermal hotspot maps, along with some cloudy language in Forest Service press releases and fire briefings. The Forest Service provided very little information to the public about what actually caused the majority of the Indios Fire to burn. That was the secret fire. The secret was that most of the fire wasn’t caused by the lightning strike; it was from intentional aerial and ground ignitions by the Forest Service called firing operations. Anyone simply reading the Forest Service’s fire news releases and listening to the fire briefings would not have understood this, and in fact most of the public still does not realize what actually happened.

The fire grew slowly for the first few days, as it burned to the northeast up and across a canyon slope. Then it suddenly turned downhill and quickly burned two miles east through the canyon bottom and up to the mesa on the other side. A few days later, the fire burned at high speed four miles to the south, although the prevailing winds were to the east and north. It appears from the aerial hot spot maps that firing operations largely caused these movements, but more information from the Forest Service would be necessary in order to confirm.

Although it was stated in the daily Indios Fire updates that the fire was being allowed to burn for ecosystem benefit and that firing operations were being used at times in support of this strategy, these explanations were extremely understated relative to what can be seen from the aerial hot spot maps. In the fire briefings available on the SFNF Facebook page, the briefing officer would wave his hand around the fire map with such comments as “we did add a little bit of fire yesterday,” and “we did put a little bit of heat in here with the helicopter.” It generally sounded as if they were implementing fairly localized back burns to contain the fire.

The May 22 Indios Fire press release stated “The Northern NM Type 3 IMT is currently moving forward with a strategy to contain the wildfire. The containment strategy means using tactical actions to manage the fire within a predetermined area.” The predetermined area was never shown on a map in press releases or fire briefings, nor was the approximate acreage of the predetermined fire containment perimeter provided. The “containment strategy” often involves greatly expanding a wildfire, while attempting to contain the expanded fire within a predetermined perimeter. That is very different from the conservation strategy of simply allowing naturally-ignited wildfires to burn in a relatively natural way for ecosystem benefit, which is highly supported by conservation scientists and conservation organizations. The agency was igniting fire far beyond back burns and burn outs, and was essentially implementing a large-scale prescribed burn without the required NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) analysis or public inclusion. Planning was being done on-the-spot.

Since the size and location of the predetermined area was not publicly available in Forest Service media, I personally attempted to find out the size of the predetermined area, and to obtain a map of the potential perimeter. I also wanted to find out why the Forest Service believed this kind of wildfire expansion operation was safe to implement in such windy and dry weather conditions. I was provided with only unhelpful and non-specific information and advice from Forest Service personnel such as – “The incident objectives you see on Inciweb [interagency incident information management system] are used to determine the specific firing operations which, like wildfire, are dynamic. Since Forest Plan direction is listed on the Inciweb objectives, I would suggest looking at the Forest Plan for insight into what those are.”

There was just one sentence on Inciweb regarding the Indios Fire management objectives – “Incident objectives include protecting values at risk and meeting Santa Fe National Forest Plan objectives by reintroducing fire into a fire dependent ecosystem.“ The Santa Fe National Forest Plan states, “When conditions facilitate safe progress toward desired conditions, consider managing naturally ignited fires to meet multiple resource objectives concurrently (i.e., protection and resource enhancement), which can change as the fire spreads across the landscape.” Nowhere does the Forest Plan state that the Forest Service can intentionally greatly expand wildfires utilizing aerial and ground firing operations.

None of this addressed my questions regarding the specific objectives and plans for managing the Indios FIre. Since the Forest Service was creating fire lines to contain the expanded fire, it

was clear that they must have had an approximate plan for the containment perimeter that they intended that the fire could potentially expand out to. Yes, fires are dynamic situations, but still there had to be a potential perimeter before deploying bulldozers and cutting and burning fire lines.

Jonathan Glass of Public Journal eventually located a federal interagency repository map from May 21, the third day of the fire, containing an 18,218 acre “Indios Fire Potential Perimeter.” The fire was 688 acres on May 21st, so apparently the Forest Service planned that the fire would be expanded and contained in an area up to 26 times its size at the time. However, the agency chose to not make the size and map of this containment area reasonably publicly available, even when specifically requested. Also, the Forest Service must have believed they had justifications for expanding a wildfire during such risky fire conditions, but they did not publicly reveal them in any substantive way.

During the 2023 Pass Fire in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest and Wilderness, the Forest Service published a map on their Facebook page of the planned fire perimeter. The fire eventually filled that perimeter with a high level of precision, with the assistance of Forest Service firing operations. That the Forest Service actually made public to what extent they wanted to expand the fire, even if they were not clear about the extent to which they were causing the landscape within the fire perimeter to burn, was possibly due to publicity by a few fire management watchdogs about the huge expansion of the 2022 Black Fire. During management of the Black Fire, the Forest Service carried out aerial and ground firing operations that more than doubled the size of the fire and burned most of the Aldo Leopold Wilderness, including important natural resources, and Sierra County infrastructure.

The SFNF seems to have reversed that recent trend towards more openness, and contradicted its many recent statements about wanting better public communication, by largely obscuring their intentions to complete widespread intentional burns while managing the Indios Fire. Even after the Indios Fire operation is complete, we will almost certainly still not have any official estimate of how much of the fire the Forest Service ignited, versus how much burned due to the original ignition combined with the elements. There will simply be one number given for the size of the fire – the total acres that burned during the fire and fire expansion. We need to know what the Forest Service is doing during fire management operations so the potential risks and consequences of the agency’s wildfire management strategies can be effectively evaluated.

Language concerning fire management operations has become increasingly obscure and confusing. At first the Forest Service described progress on managing the Indios Fire as the percent of the fire contained, but after May 28 the term ”completed” was used. According to the agency, percent completion comprises a broad mix of Forest Service objectives – it’s “an indication of the total amount of work being accomplished on the ground relative to how much they intend to accomplish.” But since they never told us how much they intended to accomplish during the Indios Fire, providing the percent completed did not clarify to what extent the agency had completed expanding the fire to burn landscape within the predetermined perimeter. Below an Indios Fire briefing on the SFNF Facebook page, a bewildered local commented – “I just wish someone would tell us [how] much of the fire is being contained, how many acres are still burning? Or is the fire continuing to expand because of the completion goals?” Another asked, “What is the percentage of containment within the percentage of completion, please, since you mentioned it as a component of completion?”

All of this was occurring at the start of the New Mexico fire season, when fire risk is at its highest. There were strong winds throughout the wildfire and fire expansion operation, and a red flag warning at one point. This was very reminiscent of the conditions under which the Forest Service ignited the Las Dispensas prescribed burn, which erupted into the 2022 Hermits Peak Fire. Due to hazards from the expanded Indios Fire, the local Sheriff’s Department put a nearby ranch on “Set” status for potential evacuation.

One might hope that after the three major wildfires of 2022, ignited due to three separate SFNF escaped prescribed burns which burned a total of 387,000 acres and burned out entire communities, the Forest Service would become much more careful about putting forest and communities at risk. They do not seem to have become substantially more careful. Firing operations planned and implemented essentially on-the-spot to expand wildfires are likely much more risky than prescribed burns which are planned in advance within a NEPA-analyzed project, and also more risky than allowing a wildfire to burn without adding substantially more fire. Add in dry conditions and high winds, and this strategy just seems reckless. Given the trajectory on which the Forest Service is continuing to manage fire, it seems extremely likely that we will have more escapes of intentional fire that will over-burn forests and burn communities.

Currently, the Indios Fire operation appears to be in its final phase, at 11,500 acres. Some rain has fallen since June 8th. At least so far, the fire has burned largely at low severity, and fuels were consumed which may reduce future fire risk in the area. In terms of Forest Service objectives, it was a very successful operation. But the Forest Service is playing Russian roulette with our forests and communities by implementing large-scale intentional fires under the wildfire management umbrella, without advanced planning and in risky conditions. And, this is done without clearly informing the public of what they are doing – or even answering legitimate questions. They are sowing the seeds of even more public confusion, fear, mistrust, and anger, but most of all they are putting what we value so deeply at risk.

The Forest Service seems to be taking the viewpoint that if the rules do not say they cannot utilize a fire management strategy, such as greatly expanding wildfires with firing operations, then they can do so. In addition to a coherent and transparent national wildfire policy, there needs to be much clearer guidelines in forest plans about how fire can be “managed,” including direction that the agency cannot implement categories of actions that it is not specifically allowed to implement. It is necessary to revise forest plans so risky fire expansion operations cannot be carried out, and so there are reasonable parameters for managing naturally-ignited wildfires for resource benefit. And the agency must be required to be genuinely transparent about how fires are being managed.

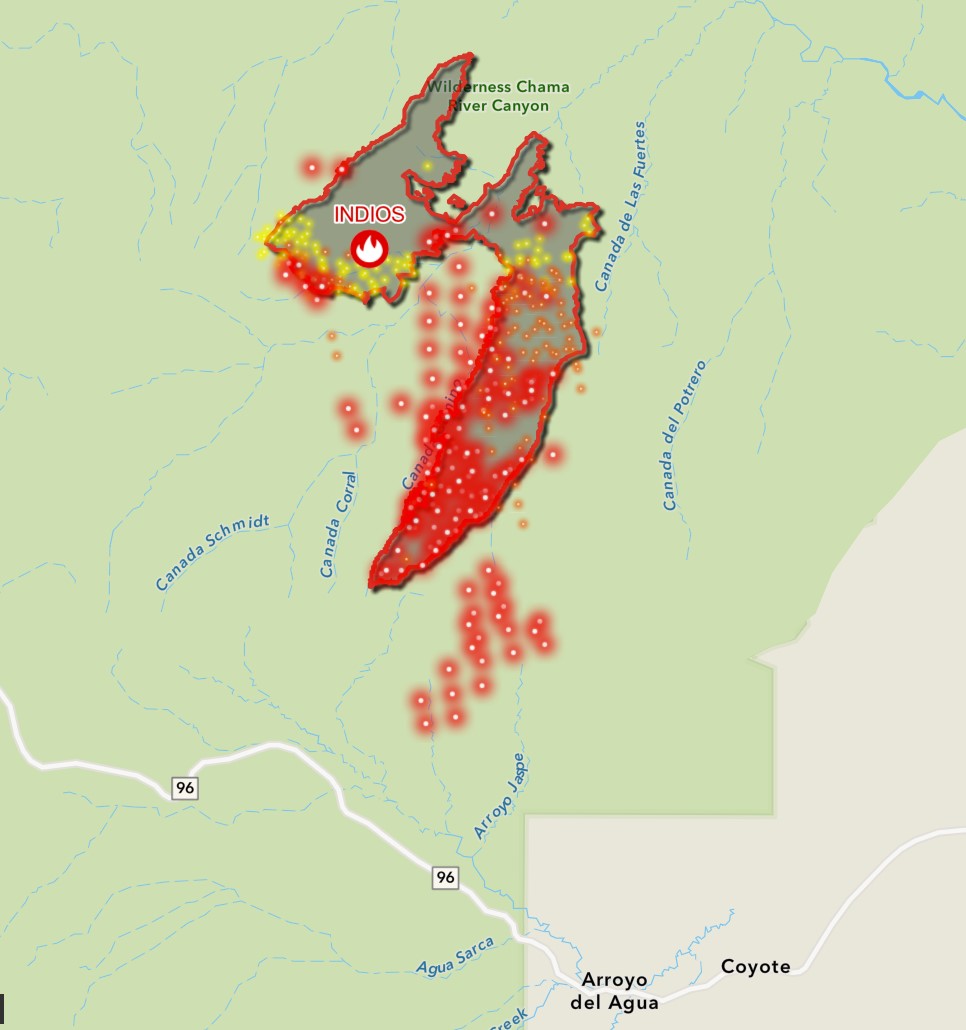

Indios Fire on Firemappers – 2024-05-27 232334 May 27, 2024 Observe firing operation hot spots, carrying the fire to the south towards highway 96. Not all hot spots are firing operations; some are simply heat from the fire, but the more or less semi-straight lines of hot spots generally represent aerial ignitions.

Indios Fire on Firemappers – 2024-05-27 232334 May 27, 2024 Observe firing operation hot spots, carrying the fire to the south towards highway 96. Not all hot spots are firing operations; some are simply heat from the fire, but the more or less semi-straight lines of hot spots generally represent aerial ignitions.

Thank you Ms. Hyden.

Good job digging up those details. Though i’m in a different region of the country, that was illuminating report to read. I think it generalizes well–really highlighting the regional breakout of fire management strategies and importantly, those manager’s openness to informing the public instead of hiding behind the a bureaucratic wall of silence.

Cheers!

I certainly understand Sarah’s frustration with this situation, especially given the previous history on the Santa Fe NF. Maybe I missed it, but did they hold public meetings to explain their operational plans and answer questions? Another option in the future would be to attend the morning briefings where there is a lot of information to be gleaned. These are not closed to the public.

I do disagree with this statement “and also more risky than allowing a wildfire to burn without adding substantially more fire.” This is not true. There is a real threat the longer a fire burns that it will be exposed to a major wind event, and then it can be a Katie bar the door situation. It is better to help a fire along with lighting operations while you have good burning conditions, than it is to just let it do its thing. I saw this firsthand when I worked on the Kaibab NF. We learned to be more aggressive and help the fire to meet its prescribed boundaries, in order to limit the burn time.

From Sarah’s description, it does look like the fire burned under fairly reasonable conditions and I am sure that was all part of the consideration. I must say though, that those folks on the Santa Fe have some guts pulling this off after the recent history. They absolutely need to be transparent though, as Sarah is asking, if they ever want to build back the public’s trust.

The USFS held almost daily briefings that were available on the USFS Facebook page, which I provided the link to. I watched them and quoted one of them in the post above.

The USFS made the fire’s potential perimeter 26X the size of the fire when they created the perimeter. It’s pretty clear that they intended to expand they fire, turning it into a NEPA-less prescribed burn. They didn’t need to do that. There were strong winds almost every day during the fire, and a red flag warning at least one day, which made such an operation risky. I don’t see how the fire could have turned to the south like it did, against the prevailing winds, without the firing operations igniting it to the south — and you can see from the #firemappers maps that it was ignited to the south. So that was just an intentional fire, IMO, and not related to management of the Indios Fire.

The USFS simply doesn’t need to do risky operations like that, especially in windy and dry weather, so whether they do it fast or slow is not the issue. Yes, they pulled it off this time, but don’t have a good track record on the whole in the SFNF.

I hope that I did not give the impression that I think your concerns are not valid. I absolutely think that they are. I am glad that people like you are speaking up. It probably would be good for each Forest to go through the NEPA process, to make a decision on how they will utilize managed fire and go through extensive public engagement. People that live in or near these Forests deserve to be heard.

The FS is under tremendous political pressure right now to do something about the “wildfire crisis”. Congress has provided them with huge budgets and they expect something to be done. As I recall, Northern New Mexico no longer has a significant timber industry to commercially thin the forests, so managed fire is seen as one of the tools left in the toolbox. But it needs to be done right. The public can play a major role in making sure they do things correctly.

Thanks Dave, I agree with all of that. But it also needs to be considered that what has worked in the past may no longer work in our drying climate. The USFS made a lot of mistakes during the three 2022 SFNF fires caused by escaped prescribed burns, but beyond that I believe a fundamental re-thinking is needed. We have such different conditions now with the warming and drying climate that pretty much everything needs to be put back on the table. If any kind of intentional burns are done, I think they need to be done with a whole new mindset, that it’s a risky operation (especially in dry forests) and should be done under relatively ideal conditions with plenty of fire fighting resources available. I think mandated “quotas” are just inviting more intentional wildfire escapes.

It’s so interesting how much fire management has changed since Dave roamed the Kaibab and we both had offices next door to each other in the Black Hills SO. Read this blow by blow of the progress of the million-acre Dixie Fire in 2021. Firefighters lit 60 percent of the burned area on purpose. Or the North Complex where self-described “widespread firing operations” in the teeth of red flag warnings resulted in a 194,000 acre run on September 9, 2020, killing 16 civilians and killing 400 cattle on the Davies Ranch. We are no longer falling back to the next best ridge. We are blowing up huge forested areas unilaterally without public involvement about whether wildfire use is a good idea and no disclosure of cumulative effects so far. Briefings are no substitute for following administrative and substantive laws. CEQ Alternative arrangements for wildfires did not cover purposeful burning outside of NEPA NFMA APA etc. All of us planners should answer Sarah’s question to the SFNF: Show me where free range burning is authorized in law, in the annual WFM “emergency fire suppression” authorization, in LMP objectives, and especially how giant comprehensive fires like Hermits Peak and Black achieve multiple use objectives, protect old growth, and protect riparian areas and T&E core habitat. The current wildfire use policy is extralegal, IMO, and will soon end when the Supreme Court overturns the Chevron deference that forced courts to bow to agency judgement in place of law, regulation, and policy.

https://the-lookout.org/2023/09/08/dixie-fire-firing-operations/

Frank, not sure that will help. It seems to me that someone would actually have to litigate arguing that this management is extralegal. But I’m not a legal expert.

A question unasked and unanswered is what about Forest Plan Standards? Core T&E habitat. Riparian Zones of Concern. Recreational uses. Maintaining accessible roads and trails. The SFNF has burned a quarter of the Forest since 2022. 28,000 acres in the previous decade. Wouldn’t we think that represents a changed condition that would trigger a reboot of the Plan?

Ah, the good old days, Frank! I do agree that things have changed and maybe not for the better. The FS has a problem with the “trust us, we know what we’re doing”. They need to go through the effort of actually listening to people. I have come around and I now believe that they should do programmatic NEPA on each Forest’s managed fire program. I think that is a good idea. They also need to do more than just go through the motions of taking people’s comments. They need to actually consider the comments and make adjustments. Here on the Black Hills, they are doing scoping when all of the units in a timber sale have already been marked. Kind of gives one the impression that it’s already a done deal. I may not agree with you on everything on this stuff but I am glad you are stirring things up. That’s a good thing!

Remanding that portion of the SFNF to the Jicarilla Apache can’t happen soon enough so that part of New Mexico can be restored to pre-colonial conditions as soon as the ink is dry.

“Firespeak” is definitely a big problem. Sadly, they think they are communicating clearly instead of speaking buzzword salad.

Ah, the old shell game the Forest Service likes to play with regard to “where is the NEPA?” They point to the forest plan for where relevant decisions were made (and presumably evaluated), but when the plan was developed they actually wanted to make sure they kept their options open. Sarah is right in saying, “there needs to be much clearer guidelines in forest plans about how fire can be “managed,” including direction that the agency cannot implement categories of actions that it is not specifically allowed to implement.

Let me suggest a forest plan standard that would do something like that: “Wildfires can be managed to achieve forest plan objectives only in areas where site-specific plans to do so have been prepared (in accordance with NEPA procedures).” We looked at an example of that here (including a comment on the Indios fire): https://forestpolicypub.com/2024/05/20/indirect-containment-for-san-juan-wildfire/. (I don’t see why this directive couldn’t also be done through a letter from the Chief, at least on an interim basis.)

Well my idea was that the FS should stand down from plan revisions and the MOG effort (now too late for that I guess) until they had done fire use NEPA with plan amendments. It’s not too late..to stand down plan revisions and focus. I think it’s one thing a wide range of people (who usually disagree) agree on.

So I see now Region 3 may have all the fire acres they can handle? Given my recent “education” on the TMR, and me thinking I really knew what it was, the fire initiative to burn up as much as possible, as quick as possible, is now a given! I do not believe anything the FS says anymore, not a damned thing…….

What’s the TMR?

I think it’s a government acronym for “Too Many Regulations,” but I’m not certain.

Travel Management Rule…… and all its glory/misinformation.

An interesting and timely footnote to this discussion referring back to the Hermit’s Peak-Calf Canyon Fire.

https://sourcenm.com/2024/06/18/feds-try-to-skirt-responsibility-in-lawsuit-for-people-who-died-after-states-biggest-wildfire/

“The duties of managing the forest, including igniting prescribed burns, “all afford government employees significant discretion in weighing policy considerations and multiple objectives inherent in fire management,” they (government attorneys) wrote in a February motion to dismiss.”

But the discretion of federal land managers is supposed to be tempered by prior public participation in the NEPA process. If they have not done that properly, could it be that they are outside of the “discretionary function” exception in the Tort Claims Act?

(What seems to be the key question in this case is whether Congress has indicated in its response to this fire that the agency was not exercising discretionary functions in managing the fire.)

A Historic opportunity knocks. With the SCOTUS set to overturn the Chevron deference, they will no longer be able to simply assert wildfire use meets Forest Plan objectives. Wildfire use is disastrous for the full suite of Forest values whether you’re an environmentalist or a tree faller. This is not to say there is no good fire. This is to say our good people don’t have the skill and understanding or experience to light giant fires 10 miles away from the fire flank of a fire in red flag conditions and sky high ERCs without doing terrible damage including killing civilians and trapping livestock and wildlife. Our fire forces and increasingly inexperienced line officers ingenuously claim they’re doing it for firefighter and public safety. Expanding. A 100,000 acre fire to a million acres does not result in safer conditions for anyone. They need to pause and engage the public with full disclosure of effects one rigorous public involvement. Oh, programmatic EISs and RODs with actual objections being honestly considered. National. Regional. Unit. The hubris of current Forest Service leadership is about to turn and bite them. When SCOTUS acts any moment now, we will launch a request for a TRO followed by a permanent injunction on wildfire use and giant big boxes pending changes in regulations and policies that comport with administrative and substantive laws. Not to mention the misappropriation of WFM “emergency fire suppression” funds etc.

Hi Frank: I hope you are right about SCOTUS and the Chevron deference — you do seem pretty confident! If that would result in an immediate injunction against so-called “managed” wildfires and “wildfire use” nonsense, that would be wonderful! This craziness and destruction have gone on way too long and DC has been more of a physical and economical threat to the western US than Moscow or China could ever be. The Japanese tried to burn our forests in WW II and failed, but DC has been doing a masterful job for more than 30 years now, and with no repercussions or apparent shame. Should have been a learning experience long ago.

Frank, I’m not legally knowledgeable, but I would think an argument could be made that NEPA should be done with or without any SCOTUS ruling. Am I missing something?

Chevron deference typically applies to an agency’s interpretation of a statute. It’s less clear how changes in judicial review at that level may filter down to judicial review of how an agency interprets its own regulation, or how it interprets its own policies like forest plans. And “whether wildfire use meets Forest Plan objectives,” is also a question of scientific fact, where judicial deference tends to be broadest.

I think the problem with litigating whatever this is is identifying the agency action that is illegal, and doing so in a manner that allows litigation to be an effective tool for addressing it (considering injunctions and mootness). Doing that is necessary to determine what law to apply, such as NEPA (or the Tort Claims Act).

When the US Constitution was written the Federalists argued for a strong central government with co-equal branches but today neo-Federalists advocate for a weaker central government with a strong unitary executive.

Two days before Donald Trump’s attempted takeover of the United States in 2021 John Eastman was summoned to the Oval Office to share some exotic extralegal scenarios then as he left a Santa Fe restaurant in 2022 he was frisked by federal agents who seized his iPhone Pro 12 presumed to contain incriminating evidence of Trump’s attempted autogolpe. Presumed unindicted co-conspirator Eastman knew Jeffrey Epstein through impeachment lawyer Bruce Castor and through Alan Dershowitz, also believed to be a pedophile.

But, in 2023 with direction from Eastman and others the Trump-packed SCOTUS reversed environmental protection for a majority of American citizens and enabled the corporatocracy to pollute at will. Today, Republicans and their toadies cry government overreach while waters of the United States or WOTUS architects regroup for another round in Congress as Eastman and other conservatives work to kill the legal doctrine called the “Chevron deference.”

Yes, the US Environmental Protection Agency and US Fish and Wildlife Service are within the Executive Branch and as Commander in Chief the president could simply order the Army Corps of Engineers and all to stand down.

Trump’s lawyers are arguing that a unitary executive could launch the extraordinary rendition or worse of anyone anywhere anytime without due process because he can. But the Supreme Court of the United States is in a box: if it rules the unitary executive is immune to prosecution President Joe Biden could call for the removal of every Republican who incited insurrection. And while Trump is a clear and present danger to national security and his imprisonment at Guantanamo Bay is an intriguing goal house arrest, a gag order and loss of passport is probably adequate if POTUS Biden orders it.