The Breakthrough Institute posted an interesting report today- so shout-out to them for digging into the litigation question. They are mostly interested in litigation and possibly permitting reform affects infrastructure projects, but, as usual, Forest Service vegetation projects continue to play a starring role in the NEPA litigation drama. I’ll excerpt the main points they make about the FS. Others are welcome to add their thoughts.

Breakthrough Institute analysts, in collaboration with legal experts at Holland & Knight, compiled and analyzed 387 NEPA cases brought to the U.S. appellate court system over the 2013-2022 period and categorized them by project type, environmental review, length of judicial review, federal agency, and plaintiff. Our results indicate that NEPA litigation overwhelmingly functions as a form of delay, as most cases take years before courts ultimately rule in favor of the defending federal agency.

As Congress deliberates reforms to NEPA, it is essential that policymakers recognize the degree to which the legal status quo prioritizes procedure over outcomes. To enable more effective environmental review, reforms should minimize the potential for extended, unproductive legal battles while still promoting the fair assessment of environmental impacts.

Here are their Key Findings:

Between 2013 and 2022, circuit courts heard approximately 39 NEPA appeals cases per year, a 56% increase over the rate from 2001 to 2015.2

• Agencies won about 80% of the 2013-2022 appeals cases, 11% more per year than from 2001 to 2004, 8% more than from 2001 to 2008, and 4% less than from 2009 to 2015.3 The rate at which agencies’ reviews are upheld is high, meaning these environmental reviews are seldom changed as a result of litigation.

• On average, 4.2 years elapsed between publication of an environmental impact statement or environmental assessment and conclusion of the corresponding legal challenge at the appellate level. Of these appealed cases, 84% were closed less than six years after the contested permit was published, and 39% were closed in less than three.

• Among the challenges, 42% contested environmental impact statements, and 36% contested environmental assessments. Agencies won about 80% of challenges to both.

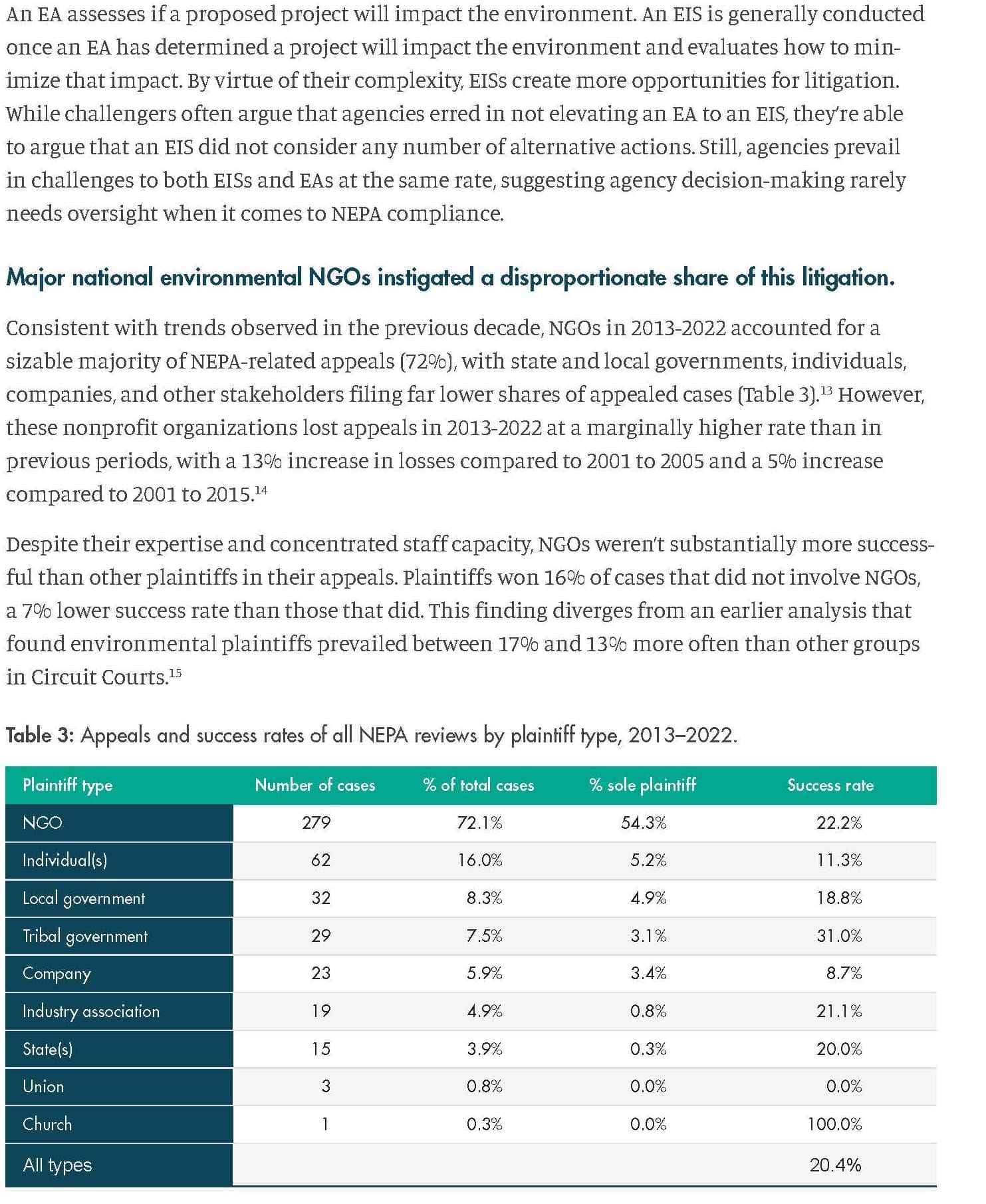

• NGOs instigated 72% of the total challenges. Of those, just 10 organizations initiated 35% and had a success rate of just 26%, merely 6% higher than the average for all types of plaintiffs.

• Only 2.8% of NEPA litigations pertained to agency assessment of environmental justice issues.

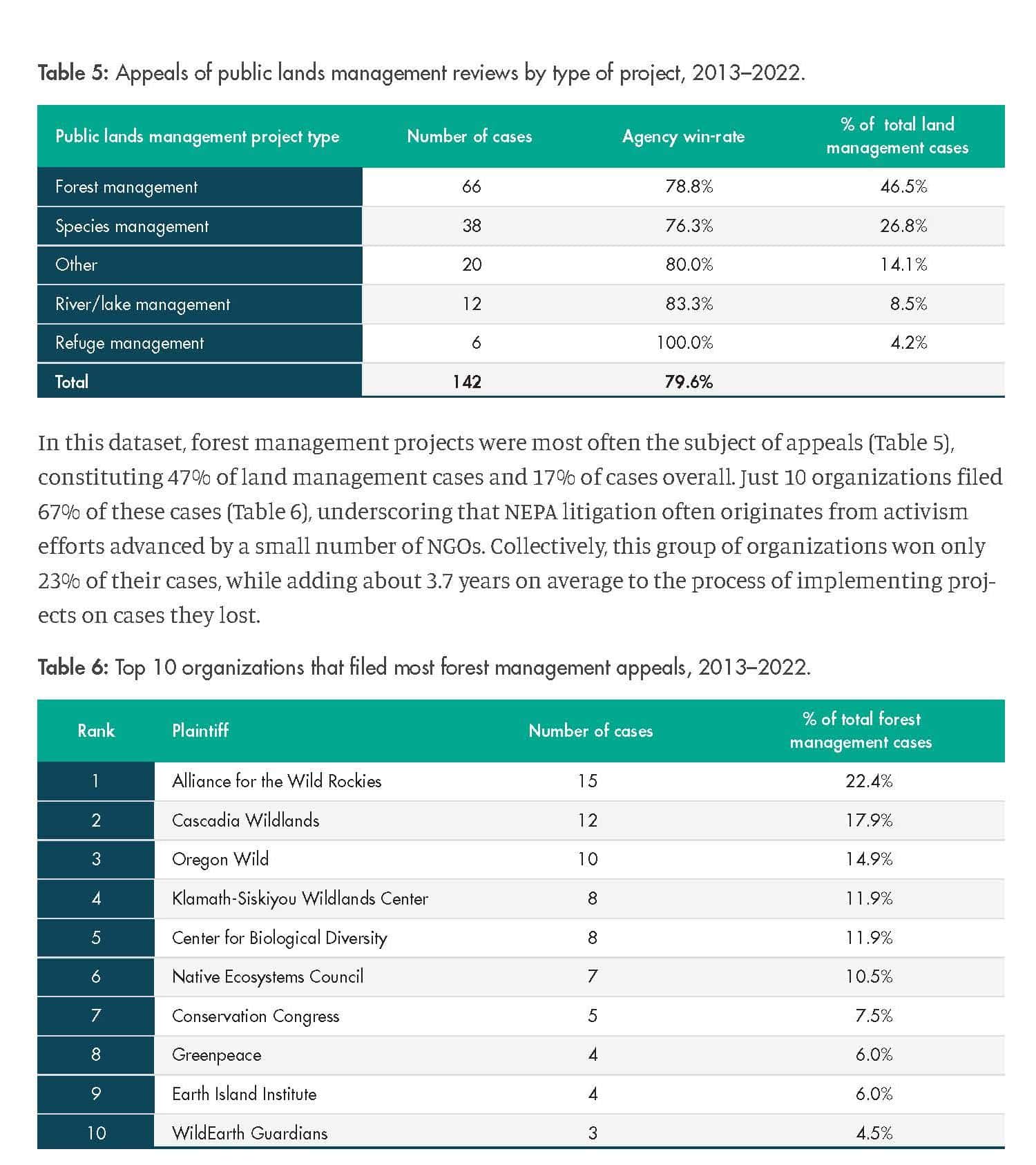

• Public lands management projects were the most common subject of litigation (37%), the greatest share of which (47%) challenged forest management projects. Just 10 groups filed 67% of the challenges to forest management projects and collectively won only 23% of those cases, adding 3.7 years on average to the process of implementing the 77% of projects on cases they lost.

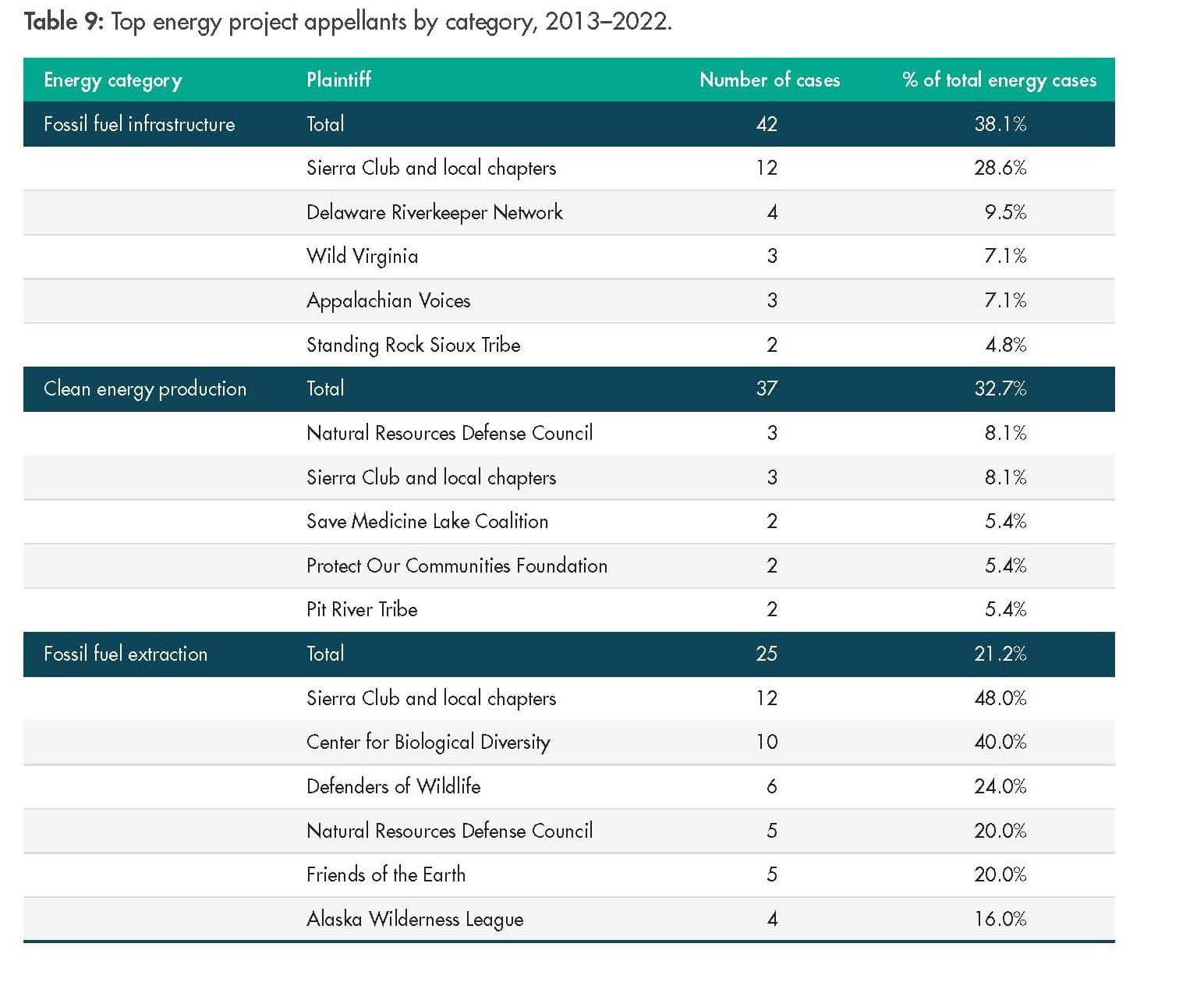

• Energy projects were the second most common subject of litigation (29%). Litigation delayed fossil fuel and clean energy project implementation by 3.9 years on average, despite the fact

that agencies won 71% of those challenges. NGOs filed 74% of energy cases, with just 10 organizations responsible for 48% of challenges.

We’re #1! We’re #!!

Forest management projects were the most common subject of litigation.

Despite public outcry over NEPA’s impact on clean energy deployment, energy projects don’t constitute the largest share of legal challenges in this dataset. Instead, the majority (37%) of total NEPA challenges contested public lands management projects. The U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management together manage the majority of

federally owned land in the United States, about 437 million acres.25 A NEPA review is required whenever these agencies perform management activities, like removing dead trees or building roads. This highlights a key distinction between the requirements NEPA imposes on public lands management agencies and those that focus on building infrastructure. Where NEPA acts as a mechanism to regulate private industry activity when permitting mines or wind farms, it also governs how land management agencies execute their core, legislatively mandated responsibilities. Thus, NEPA litigation poses a unique challenge for these agencies, allowing the public to contest the minutiae of their every decision.In this dataset, forest management projects were most often the subject of appeals (Table 5), constituting 47% of land management cases and 17% of cases overall. Just 10 organizations filed 67% of these cases (Table 6), underscoring that NEPA litigation often originates from activism efforts advanced by a small number of NGOs. Collectively, this group of organizations won only 23% of their cases, while adding about 3.7 years on average to the process of implementing projects on cases they lost.

Here is Breakthrough’s broader look at litigants for all projects.

Re: Litigation in R1 – while some might say that Mike Garrity never met a lawsuit he didn’t like, R1 is, to be fair, a bit different from the other kids. One argument enviros made in favor of the Roadless Rule was that it actually didn’t matter all that much. Most roadless areas, they asserted, were “roadless for a reason.”

“Let’s not kid ourselves. Most roadless areas in our National Forests are roadless for a reason,” Munson said. “They are usually marginal timber areas where logging is cost prohibitive.”

https://www.tu.org/press-releases/conservationists-sportsmen-can-both-benefit-from-roadless-policy/

Leaving aside the Tongass for a moment, one place in the lower 48 where this statement was not accurate was (and still is, I suspect) R1. There are a number of roadless areas within R1 that could be profitably logged. (I’ll caveat this statement – it was true years ago, but I don’t now how the shrinking timber processing infrastructure – I’m lookin’ at you, Pyramid – might have changed this.)

Perhaps more flexible NGOs/regional management could have reduced litigation in the region. But my sense is that R1 was to some extent dealt a contentious hand. It would be interesting if folks with more recent experience in the region have views on this question.

R1 also has a large number of wide-ranging at-risk species subject to ESA and NFMA diversity related legal claims (grizzly bears, Canada lynx, wolverines, bull trout). That’s not necessarily a spillover into NEPA, but it’s part of the overall litigation picture.

And yet, Colorado has lynx, I would think Idaho has bull trout, Wyoming and Idaho have grizzlies..so perhaps there’s something else going on. Maybe someone who has worked both in R1 and neighbor Regions can give their ideas?

This is useful information. The 23% success rate for litigants is telling. I wonder how much of this was due to Chevron and how or if things will change going forward?

I am much less knowledgeably about this than Rich J. and other legal folks at TSW, but these cases seem to be all about projects and not regulations. Chevron only applies to regulations.

Thanks for this info, Sharon. The biggest surprise to me was this invalidates the truism that agencies should do an EIS because they are easier to defend (in part because it takes the “should have done an EIS” claim off the table). Same success rate for EISs and EAs.

I was kind of struck by conclusions like “merely” 6% higher success rate for NGOs, 10 groups won “only” 23% of the cases, and “just” 10 organizations were responsible for everything. It suggests some preconceptions by the authors that I guess I don’t share, and maybe an agenda bias.

I think it’s important to recognize that these are appellate court decisions. There are a lot of agency losers at the district court level that don’t get appealed (or get settled), and I’m going to speculate that the government is more choosy about what it appeals than plaintiffs are. This could lead to a better track record on appeals for the government, and understating the overall effectiveness by plaintiffs.

A practical lesson for managers might be that if you want to minimize the time and cost of a project, you need to know your audience and their issues, and you do what you can to avoid litigation, including maybe looking for a different project. Or if you know you risk litigation you’d better ask for the time and money it’s going to take.

So that part of the study, as I read it, lumped all agency/kinds of decisions together. We’d have to ask them to separate out the forest management decisions to be sure that FS cases in veg management were the same (EAs and EISs were the same). Even if that were the case, that would mean to me that the FS did a good job of where to do EAs vs EISs.

So I think the Breakthrough people were using these data to paint a bigger picture for possible new energy infrastructure. So 6% higher is not all that meaningful. if say NGO’s were 50% higher, there might be something worth looking at.

I can’t put words into the authors’ mouths, but it seems to me that they are making the case that for infrastructure projects, it’s not that NGO litigation is so successful, but that it lengthens the timeframe, which causes uncertainties for project developers and may cause them to drop out. The difference with FS projects is that FS folks come to work and keep slogging away year after year with litigation, while new, say, geothermal develops could look at the numbers and just give up and do something else. Wait, maybe that was another paper I read, but this study supports that conclusion.

“Just 10 organizations were responsible”.. well, I don’t think the Boards (nor staff) of those organizations are necessarily representative of the population as a whole. I don’t think Breakthrough is making that point, but I am. Similarly we find NRDC and Sierra Club litigating clean energy projects. So we could ask “should small groups have that much power over what goes on on federal lands?” when both the Admin and the Congress have lined up supporting low carbon energy?

Here’s their conclusions.

“Overall, this analysis sheds light on the need to reform judicial review procedures under NEPA.

Currently, litigation rarely produces substantial changes to environmental outcomes, instead

creating a platform for a narrow set of well-resourced NGOs to further their missions. This status

quo not only drains agency resources for challenges that are seldom successful, but pulls

resources from services that actually improve environmental outcomes, like forest management.

As Congress debates reform, it’s essential for policymakers to prioritize pragmatic solutions that

streamline the NEPA review process and empower agencies to fulfill their obligations efficiently.”

Certainly, not doing any projects that AWR won’t like is certainly an option for those in Region 1 but justice-wise, should one group be calling the shots over elected officials and the rest of the public?

Well that last one is the trillion dollar question, but “elected officials and the rest of the public” authorized a policy, not a particular project. And those same officials (representing the rest of the public) passed laws that gave “one group” (or an individual) a right to oversee how the policy is implemented. And the Breakthrough Institute can believe and advocate that “forest management” necessarily “improves environmental outcomes,” so nobody should get to question that, but how much should what one group thinks matter?

Sharon, your TSW posts have been superber (to make up a new “word”) than ever. Much appreciated! The number of cases is interesting, but I’d like to have info on the impacts — the number of acres affected, for example. Several of the litigated projects were very large, in terms of size. For example, the BLM’s Late Mungers Integrated Vegetation Management project, where proposed treatments include prescribed fire, small diameter thinning, commercial thinning, and selection harvest on approximately 7,435 acres. Litigants challenged only harvesting in LSRs, but the entire project no doubt was delayed.

https://www.opb.org/article/2024/05/30/judge-rules-against-blm-mungers-timber-sale-southwestern-oregon/

All I did was post what the Breakthrough folks came up with. I agree, if we had $ we could look at acres, acres removed due to settlements, delays and sites burned destructively in areas where treatments were not done.

Here’s what I see, though, and I could be wrong.

Our “permitting reform” friends frequently use FS data to make their case, but at the end of the day, they want to fix permitting for other kinds of projects.

Someone like PERC might be interested in doing more work, but I think most fuel treatment people have given up on Congressional reform- because the “permitting reform” people have a lot more clout and they haven’t been able to get it. So why study our veg management problems? There’s nothing we can do politically, and it’s just depressing to think about and elucidate exactly how bad it really is, other than what our eyes can see. Perhaps the best hope is to ride on the coattails of the “permitting reform” folks.

I thought the win number would have been larger. Great article 1st time I had seen such an analysis. When dealing with vegetation the elephant in the room is the delay. Which makes some project no longer viable. And interesting analysis would have been projects cancelled rather than being litigated. Thanks for getting the article out

Jon said:

“A practical lesson for managers might be that if you want to minimize the time and cost of a project, you need to know your audience and their issues, and you do what you can to avoid litigation, including maybe looking for a different project. Or if you know you risk litigation you’d better ask for the time and money it’s going to take.”

Could not agree more. The best way to avoid litigation is to avoid lawyers, and the best way to do that is to walk the hard yards to understand what the people in your watershed actually think. I don’t pretend that this is easy, but it is almost always easier than the alternative.

Hi Rich: What you are saying should be correct, but it is not “the people in your watershed” that are filing these lawsuits. It is national and regional environmental organizations typically located in a city far, far away. And taxpayers are covering their costs, which only encourages them more.

Watersheds should be managed by local residents like we did for thousands of years before NEPA and spotted owls. Opinion, based on news media.

That would probably involve not doing commercial timber harvest at all, in, say, Montana, because AWR seems to be against it.

But the other side, perhaps less examined, is that sometimes local groups don’t like projects either, but can’t afford to litigate and can’t interest national groups. So we are not necessarily getting the true view of all environmental concerns related to projects.

Nevertheless, the Breakthrough folks are mostly interested in how to help with the infrastructure we need to help with climate considerations, so perhaps that’s not so relevant to them.

100% agree!

Thanks for all the excellent coverage lately, Sharon! It’s interesting to frame the issue of NEPA litigation to include all energy infrastructure, because it really highlights how odd the NEPA process is applied to a living thing like forests that have a trajectory without action that may or may not be optimum for the living thing itself. I guess that framing helped me see that maybe the analyses would be more compelling if the trajectory of no action management could be better quantified and compared to quantified action alternatives. Maybe carbon is that metric of comparison? Or fire behavior? Or resilient habitat? Seems like with sufficiently complex models and input data apples could be compared…

Great post and conversation. I’m wondering if someone can explain how “supportive objections”, like those filed by collaborative groups, play into this dataset? In general, my understanding is that it is difficult to distinguish in most datasets so all objections get lumped together as oppositional.

Let’s ask the authors.