The National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, is the environmental bill of rights for the public, who are the legal owners of our national forests. It’s the framework in which we consider the risks and benefits of forest management projects, and attempt to avoid damaging outcomes or even environmental disasters. In the past, NEPA required that we “look before we leap,” but more and more, the Forest Service is leaping before it looks during the planning and implementation of fuels reduction projects. Often, the results are severe ecological damage, and even increased fire risk. Section 40807 of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, ”Emergency Actions,” is perhaps the final stage of the long dismantling of our NEPA rights to protect our forests.

Section 40807 authorizes the Forest Service to take “emergency actions” when an immediate response is necessary to address forest-related “emergency situations.” Emergency situation guidelines were originally legislated in the Healthy Forest Restoration Act of 2003, and according to both Acts, emergency actions may be taken by the agency for relief from hazards threatening human health and safety, and for mitigation of threats to natural resources on National Forest System land or adjacent land. It is left up to the Forest Service to decide if and when an emergency situation exists on national forest land, and to choose from a list of responses which includes the removal of “hazardous fuels.” The Forest Service has recently been using emergency authority to approve and implement large-scale and aggressive commercial logging and prescribed burning projects. Such authority, which is reasonable for genuine emergencies, has been greatly expanded by the agency to the extent that the public has virtually no rights in relation to project planning.

After the Forest Service proposes a project designated as an “authorized emergency action,” it is only required to analyze two alternatives: Action (do the project) and No Action (don’t do the project) – instead of a range of alternatives, including a conservation alternative. The objection process is not allowed, and courts are directed not to issue an injunction on an authorized emergency action unless the court determines that the plaintiff’s case is likely to succeed on its merits.

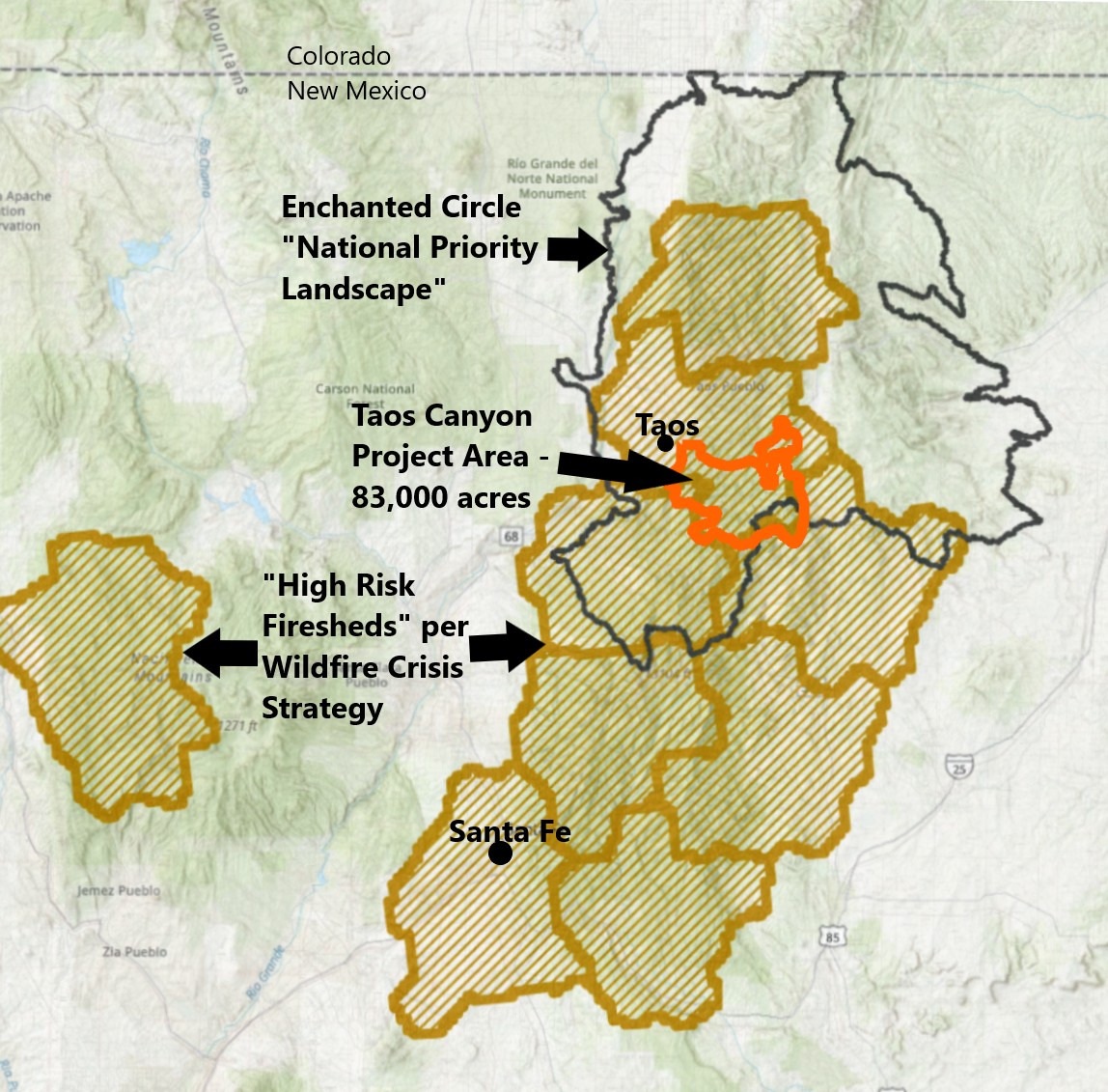

The Infrastructure Act includes 3.5 billion dollars of funding for “wildfire management,” and to implement the law, the Forest Service issued its Wildfire Crisis Strategy, which currently contains 21 “priority landscapes” and 250 “high-risk firesheds” across the west that are considered to be in potential emergency situations requiring emergency actions. These landscapes were designated by the Secretary of Agriculture with no NEPA process whatsoever. With additional funds from the Inflation Reduction Act, the Forest Service has stated its current goal is to implement treatments in 134 of the designated high-risk firesheds, amounting to 45 million acres. So far, almost a million acres of vegetation treatments have been either approved or proposed under authorized emergency action.

The Infrastructure Act was signed into law almost three years ago, in 2021. What has brought Section 40807 into my focus recently was my receipt of yet another Forest Service notice for a large-scale northern New Mexico forest tree cutting and prescribed burning project – the Taos Canyon Forest and Watershed Restoration Project. This 83,000 acre project area is just southeast of Taos, New Mexico, in the Carson National Forest.

Much of the forested landscape of northern New Mexico is within either the “priority landscapes,” or “high-risk firesheds,” meaning that the Forest Service has given itself the potential of authorizing emergency authority over almost any northern New Mexico vegetation management project.

I was stunned to read that the Taos Canyon Project was largely an aggressive commercial logging project (54,731 acres are proposed to be logged or cut), with no diameter limits for sizes of trees to be cut, no indication of how many board feet of lumber may be taken, no specifications of which species may be cut, 600 acres of logging landings, and logging on very steep slopes up to a 75% grade. Steep slope logging has not been done for decades in northern New Mexico because it is so severely damaging to dry forest floors and to overall forest ecology. The Forest Service plans to burn the entire project area, even vegetation types that have historically received only infrequent fire. And they intend to proceed with this project as an authorized emergency action. This “emergency action” will take over 10 years, even though Section 40807 states that an “emergency situation” means a situation on National Forest land for which immediate implementation of authorized emergency action is necessary.

The Taos Canyon Project Scoping Notice states that “past logging focused on the largest, merchantable pine, fir, and spruce trees” has changed stand conditions so that they have become denser than they were historically, which has caused a decline in forest health and increased fire hazard. So the answer that is provided to this dilemma is – much more logging of large and merchantable trees! A local resident who went to a Forest Service open house concerning the project was told that the intention is to revamp the logging industry in the area, including bringing in out-of-state logging contractors if necessary.

Since the 1990s, most Forest Service projects in northern New Mexico have been primarily thin-from-below projects, meaning mostly focused on the removal of smaller trees, although larger trees also get removed. Such projects are proposed with diameter limits on the size of trees that can be cut, and conservation organizations then normally strive to reduce the diameter limits to conserve the large fire-resistant trees, and to reduce the total amount of trees to be cut so the ecosystem does not dry out from the tree canopy being overly open. They advocate for projects to be carried out in ways that maintain or even improve the ecological integrity of forests, instead of decimating the structure and function of forests so they turn into human-conceived parodies of their former state. As damaging as thin-from-below can be when implemented in overly aggressive ways, the aggressiveness of what the Forest Service is now proposing for the Taos Canyon Project is on an entirely different level, almost unimaginable in a warming climate.

This project is a regression into the forest management dark ages, from which conservationists have spent years trying to move forward into a more enlightened state, with at least limited success. Section 40807 has provided the cover for the Forest Service to go as far as they choose in managing forests with aggressive and widespread extraction of trees, leaving behind eroded and compacted forest floors, decimated understories, sediment in waterways, degraded wildlife habitat and even more ecologically damaging forest roads.

This proposal can only be understood as the Forest Service taking full and outrageous advantage of the emergency power conferred upon the agency by Congress through Section 40807.

Given that Congress confers this “emergency action” authority onto an agency that has clearly gone far astray from its legitimate mission, we, the true owners of the national forests of this country, are in a bind. What can we do? We can try to challenge clearly ecologically damaging Forest Service projects, but when they are proposed and implemented as authorized emergency actions, challenges can be very difficult. It’s time for a forest revolution. The Forest Service has tacitly proclaimed through this abuse of authorized emergency action that they will provide a cynical facsimile of NEPA analysis that sacrifices the ecological integrity of our forests, and that the public has no choice but to accept it. The NEPA tenet of “Look before you leap” has turned into “leap right off the ecological cliff,” without a rational risk/benefit analysis of what we are doing and what the consequences may be.

For a forest revolution to succeed we do not have to riot in the streets, we can do it with our minds, voices, keyboards, and votes. But it must be powerful and swift. And hopefully we can also find a way to defend our forests and communities in the courts. I see two possible outcomes. The first is that the Forest Service’s almost complete control of forest project planning leads to such devastation in our forests and communities that eventually everyone sees we must change course. The second is that citizens rise up and tell those in positions of power – those who have been involved in this abrogation of our legitimate rights to genuinely participate in planning for our forests – that they must correct the course now so we can protect our forests.

What do we need to make happen?

- The Forest Service must be required to reasonably explain which emergency situations exist for each project they analyze as an “authorized emergency action,” based on a full range of the best available science.

- The Forest Service must prepare a programmatic environmental impact statement for the Wildfire Crisis Strategy, as it is a forest management program concerning “multiple actions such as several similar/connected projects in a region.”

- There must be congressional oversight hearings about how the Forest Service has been abusing its authority under Section 40807, and how it is generally spending its wildfire management dollars.

- Congress must amend Section 40807 of the Infrastructure Act so that a valid and meaningful NEPA process can take place for all federal land management projects.

I am torn between wanting easier access to management strategies that include producing wood products and concern for the lost opportunities to develop informed consent for management activities. Natural resources policies swing on a pendulum bookmarked by legitimate needs and definite abuses by both the government and environmental groups. The pendulum has swung to favor the Forest Service in both emergency actions and rampant wildfire use. The swing back will be painful. Neither government nor environmental groups win all the time.

Rather than proposing more layers of rules and regulations as many communities through out the west are burning or threatened by wildfire.

It would be interesting to hear from the folks who live in nearby communities concerning this Taos Canyon Project. And if they believe “it’s a step backwards into the dark ages of forest management” or a sensible and needed project.

I would like to hear “both sides” as well. If anyone finds that, by the FS or other groups, I’ll post.

https://www.taosnews.com/opinion/columns/skip-the-red-tape/article_ec4a975e-e212-543e-9243-39827946cdeb.html

https://www.emnrd.nm.gov/sfd/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/CWPP-Taos-Canyon.pdf

https://www.emnrd.nm.gov/sfd/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/NMFAP_2020_Version1_2020_09_28_web.pdf

Thanks for the links! Looks like it’s in a canyon. That could explain the perceived need to reduce fuels on steep slopes.

It is not a steep canyon, it’s a wide canyon. Lots of projects have steep slopes, and the FS has not logged them. Since there is currently about a million acres of emergency action vegetation treatments proposed, or in progress in the west, it’s clear it’s not just about canyons, but it is a treatment trend. Also, when you consider that in the scoping notice there is no limit on size of trees to be logged, no limit on board feet to be taken, no limit on species, and 600 acres of logging landings, it’s clear this is an aggressive logging project. Steep slope logging fits in with that.

Priorities for community wildfire protection starts at the structures and ingress-egress routes and moves outward. Too many times I have been witness to communities advocating for more logging to reduce fire risk around their community, while the private lands within the community remained a fire hazardous mess. It must also be recognized that community concern about fire risk does not make the community an expert on how to address the risk and it also increases the odds that they will be irrationally aggressive.

Many times (not in this case though it seems), these communities are also economically tied to commercial logging and benefit economically from overly-aggressive management. Like the time I was on a project field trip and it was being proposed that they needed to do overstory removal of some massive old oaks and then nuke the place with herbicides to increase the view from a fire tower. When I asked why they don’t just put a camera on top of the tower, I was told by the forester that he didn’t want to do that because his neighbor was the guy that manned the tower each summer and he didn’t want him to lose his summer job…the forester’s uncle was also one of the local purchasers. This was also a community with some of the most fuel-choked private lands I have seen, running all the way up to the local grade school.

It seems to me that projects like this always fail in court. There is always some sort of endangered species that isn’t properly considered. It really sounds more like something coming from a local Congressman, with a ‘wish list’ of what those in power want it to be. If the land is so steep, will they use helicopters to fly the logs out? Cable logging? Road building? Milling infrastructure for larger logs? Transportation costs? Funding? Personnel?

The courts won’t support any kind of ’emergency declaration’ for waiving environmental rules. It seems like ‘pie in the sky’, to me.

Good post Sarah, it is well presented and you make a good case. Is this a good project, maybe, I don’t know. The point is that the FS is making the public comment period during the NEPA process all but irrelevant. If they are doing an EA or an EIS (why bother, go the easier route, who’s watching?) you get two opportunities to comment on a given project. As stated, there are no objections allowed with this authority. What the FS does with the comments is totally up to them. There is no obligation to do anything with them other than consider them.

This is the classic “trust us, we know what we are doing” scenario. Some people may be comfortable with that and some may not. If you are not comfortable with the project and the FS did not address your comments, you can always file a lawsuit. Yeah right, anyone who thinks that has not actually looked into how difficult that is. You have to be very committed and willing to risk a lot of money to proceed with a lawsuit. Besides, this authority has limits on lawsuits.

Sarah, I think your four points are good and entirely reasonable. I am not sure how to make them happen. If you could find a supportive Senator or Representative to help push them forward, that might be your best shot. I would think that with what has happened in New Mexico recently, maybe you could find a sympathetic politician.

Thanks so much, Dave.

It feels like putting our fingers in multiple holes in the leaking dike to just keep up with comprehensive project comments and explaining the project to the readers of my organization’s forest updates, so they can comment. It hadn’t been too long since we completed the Encino Vista Project draft EA comments that the Taos Canyon Project scoping notice came out. But the Taos Canyon Project was a leap into a whole new world of environmental damage for our dry forests. Steep slope logging is just unimaginable here. Forest roads cause erosion and run off which further dries out forests, especially when they are not maintained. That area is full of decaying forest roads already, and there really isn’t such a thing as a temporary road, as forest visitors tend to continue to use them. We write the comments, knowing that they will be largely ignored. The Infrastructure Act and Inflation Reduction Act funds has made forest management feel like an unstoppable train, just barreling along.

In the warming climate, it all needs to be done much more thoughtfully, and it’s really all a series of land experiments now. We see thinned areas in the SFNF with nothing by thick gambel oak coming in, and many of the remaining trees declining and some turning brown or dying. Or there virtually is no understory, even after a few decades, except for a few grasses. An upcoming ecologist in our area wrote a master thesis on the impacts of fuels treatments in our dry forests of the Santa Fe Mountains, and has made recommendations for less impactful projects.

https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/items/e9bb3e79-5f9c-4d94-990d-50f2ae440d33

A group of conservation org. people in this area are working on putting together specific recommendations for less impactful projects in dry forests, focused on the Santa Fe Mountains Project, and for projects that really do foster healthier forests, and help to hold moisture in the ecosystem instead of drying it out. Maybe that will make a difference.

But it is an uphill struggle. I found the recent article on TSW interesting, re Randy Moore’s contention that we need new metrics for fuels treatments instead of just cut and burn as fast as possible. He is certainly correct about that, but is receiving pressure from Congress to just power forward, and treat as many acres as possible. I do talk to our elected representatives, but it’s a stretch for them to want to oppose the agency, even after the widespread prescribed burn fires of 2022. They do get there is a problem though.

I truly believe there will be a time we will all look back and regret what happened to our forests. Times have changed, and at least in dry forests, we aren’t getting good regeneration after disturbances, instead we often see forests type converting to shrublands.

So to me, that means any treatments need to be considered in a site specific way, and be light-handed, targeted and limited.

I do think the right emergency action project needs to be challenged, which challenges the use of emergency action for long term projects, which it was not intended for. I would hope it could be for the Taos Canyon Project.

BTW, there is mixed opinion about the project in the Taos area. The USFS is representing it as mostly cutting small trees at public meetings and open houses, so that doesn’t sound bad. But the scoping notice says something entirely different. You don’t need 600 acres of logging landings, and 112 miles of new or reconstructed roads for small tree cutting and pile burns. Nor is commercial logging of unlimited sized trees, or steep slope logging, which the scoping notice states that the USFS intends to do, anything like small-tree thinning. And, as I mentioned in my article, someone from the USFS provided a very different view to a local, that they are indeed wanting to start up the logging industry in the area again. I believe their written words, what is in the scoping notice, is their intention.

Sarah, a couple of thoughts. First, I think it’s important to figure out if the idea is just thinning for resilience, or if there are planned fuel breaks. Because in our country “Or there virtually is no understory, even after a few decades, except for a few grasses” that would be great for a fuel break.

Second, could you be more specific about the changes you would like to see? Fewer acres, different treatments, different locations? And are you thinking of PODs and fuelbreaks or just general treatments to reduce stems/acre and ladder fuels? Do you have another set of treatments to meet the purpose and need of the project, or do you disagree with the purpose and need?

What is happening in the Santa Fe Mountains Project, and what is proposed for the Taos Canyon Project are two very different things. But in the Santa Fe Mountains Project, there will be 18,000 acres of thinning. So it’s more than fuel breaks, although surely there will be fuel breaks. Since the project was proposed under condition-based approach, we do not really know what is going to be done.

Fuel breaks are not that effective in this area, when “fire weather” tends to include high winds. Firebrands can just blow right over them.

Generally speaking, the concept for less impactful and possibly restorative projects include thinning only in limited ways to a greater remaining tree density, making sure it’s done in the least impactful way possible, implementing prescribed burns at much greater intervals, and decommissioning forest roads. Then doing projects to help hold moisture in the ecosystem, such as promoting beaver habitation and earth works to slow down run-off. it’s important to consider mycorrhizal fungal networks, as they play an important role in healthy forests so they can hold in moisture.

Also, we know there will be wildfires, and fire has an important role in forest ecology. So the focus would be on home hardening, and treating the 100 feet around homes and other values. According to Jack Cohen’s research, and others, this is the effective way to protect homes from fire, not treating out in the forest.

I don’t think anyone is against beavers. What about mycorrhizae specifically? As I’ve pointed out before, most people don’t want fire running through their community, burning up power poles and park benches, evacuating themselves, pets, livestock and so on. Jack assumed that the problem was “protecting houses” but I don’t think it is.

The main issue with most people’s read on Jack Cohen’s work (including a couple serial posters/admins here), and even his own media push with it, is….where do all those embers come from?

It is impossible to 100% ember proof a home, despite what anyone says. Embers come from fires, and when they are in proximity to the WUI and communities and people, it’s not good.

BUT, you can make it easier to suppress a fire, or give fire crews more space and time to defend homes/communities. Jack Cohen actually wrote a very comprehensive report on that, but no one seems to ever want to reference that one.

https://www.fs.usda.gov/rm/pubs_other/rmrs_2008_cohen_j001.pdf

And then there is this one as well, where fuel treatments mattered:

https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=7375efc6a9381e68701971ec6dbd48db3818cecb

From the conclusion of first report about about the Grass Valley Fire —

Our post-burn examination revealed that most of the destroyed homes had green or unconsumed vegetation bordering the area of destruction. Often the area of home destruction involved more than one house. This indicates that home ignitions did not result from high intensity fire spread through vegetation that engulfed homes. The home ignitions primarily occurred within the HIZ due to surface fire contacting the home, firebrands accumulating on the home, or an adjacent burning structure.

Home ignitions due to the wildfire were primarily from firebrands igniting homes directly and producing spot fires across roads in vegetation that could subsequently spread to homes.

You have a lot going on there! I agree that the dry pine forests of New Mexico and Arizona require extra care, now more than ever. A lot of the research conducted in the SW in the past may now need another look. I think that the Goshawk Guidelines by Richard Reynolds provide a pretty good framework for managing pine in the SW. They try to create conditions that existed pre-settlement, a more natural way to manage ponderosa pine.

I am really troubled by the recent interest in steep slope logging. We are experiencing that up here as well. Here is a link to some research that says it may not be that effective for fire mitigation.

https://fireecology.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42408-022-00159-y

Here is a quote: “Fuel treatments on steep slopes were less effective in changing fire behavior or reducing fire severity than those on flatter ground, especially under high wind conditions (Harbert et al. 2007; Murphy et al. 2007). One case study (Henson 2007) found that areas previously treated with thinning and prescribed fire successfully slowed fire as it was backing downhill but did not impede rapid uphill runs. Fuel treatments strategically located along ridge tops, in which fuel reduction impacts coincide with topography-related reductions in the rate of spread, were considered particularly useful in facilitating fire suppression efforts (Harbert et al. 2007; Murphy et al. 2010) or reducing the probability that past fires reburned (Gray & Prichard 2015).”

In addition, the steep slope logging can be very expensive. Up here it is costing $4,000-$6,000/acre. These are funds that could be put to much better use.

I think with all of the flurry around spending money and the Wildfire Crisis Strategy, the FS may be at the point where they feel they have to be doing something, even if it does not make that much sense.

Dave, if in fact the treatment are in a canyon with the houses at the bottom

“Here is a quote: “Fuel treatments on steep slopes were less effective in changing fire behavior or reducing fire severity than those on flatter ground, especially under high wind conditions (Harbert et al. 2007; Murphy et al. 2007). One case study (Henson 2007) found that areas previously treated with thinning and prescribed fire successfully slowed fire as it was backing downhil..”

We can imagine that the fire would be coming downhill into the canyon.

I must admit that I did not put in the effort to learn the specifics of this project. If that is the case, there may be some value in thinning these particular steep slopes. For years, regular ground-based systems (rubber-tired skidders, feller bunchers, dozers) were limited to 45-50% slopes. To go steeper than that required cable operations and their use was limited due to availability and cost factors with lower quality trees. Now, the use of tethered logging systems is causing a lot of places to look at steep ground that they previously bypassed. It is still very expensive and the FS usually has to heavily subsidize these operations with the use of Stewardship Contracts (IRSC’s in particular).

My argument is that yes, thinning could provide some fire mitigation on downhill backing fires but as we all know, across a landscape, fires burn downhill and then there is a slope reversal and they burn uphill where the thinning makes little difference. What is accomplished then with all this expenditure? It is not like you are pretreating these steep slopes to make a safer environment for firefighters. Firefighters should not be on steep slopes. They should be along roads and possibly ridgetops and other logical locations. These are the areas where it makes sense to put investment into thinning and pretreatment, not on steep slopes. I will grant that there could be some limited locations where it may possibly make sense.

We are talking about the Southwest and there, I witnessed a running crown fire at 10:00 PM, downhill. The fire had travelled 11 miles already that day and a north slope was not an impediment. However, Stewardship logging and fuels removal had buffered the little town at the bottom of that slope. Burning chunks about the size of a softball were raining down on us, so anfter evacuating the ICP, I figured we would lose the entire town; you talk about intense!

Nary a house was lost that night! The firefighters credit a safer zone to actively engage the fire, and the resulting canopy bulk density would no longer support a crown fire. There is that….. but that entails maybe 20 – 30 sq feet BA/acre.

An old term not highly thought of also comes to mind; if there are those slopes that really are too expensive and/or technically challenging, “fuels isolation” can come into play. Just don’t get carried away with that option….

The sites that came back with grass only understory, is it ponderosa and native bunch grasses? There are many sites where that is the natural climax conditions with the natural fire regime. I often view sites with native bunch grass understories as true dry forest sites. I do believe foresters can go nuts sometimes and take way too much. For example, in my neck of the country where we have ponderosa and native grass understories, I’ve had foresters say the treatments they did that left 30% canopy cover was still too dense. When I suggested there was open growing space and none of the trees were competing with each other and they couldn’t actually reduce fire hazard more, they said the historical range of variation was for stands to have fewer trees. My response was the historical range of variation was for the residual trees to be 3 times larger than what they left, but all the big ones were logged decades ago. How many 20 inch trees does it take to get a single 30 inch tree? It’s definitely not 1:1. The stands were also totally devoid of snags and downed wood and were so “healthy” there would be very little recruitment of snags and wood.

A suggestion for those sites covered with dense sprouting oaks. I recommend the suckers of the sprouting stumps be thinned down to 3-5 of the best leaders in the spring, before suckers get too large. It can be done with loppers when they are small. The oak will then put energy into those residual leaders and you’ll get larger oak back much faster, including acorns for wildlife, shade for the site, and it will reduce fire hazard.

Remanding public lands in New Mexico to Indigenous communities can’t happen fast enough.

So what would that outcome be? What if it isn’t to an idealized notion of what “indigenous” did/do? Then what?

These nearly 1 million acres of so-called “emergency action” logging projects under Section 40807 of the Infrastructure Bill have gone almost unreported in media, despite dozens of press releases to nearly all journalists writing on the topic of wildfire and forests.

Glad to see this article making the rounds since the public can no longer count on mainstream or even most alternative media to do its job anymore.

Josh, you and I might not agree on much, but it sounds like neither of us are impressed with the current media landscape.