The Forest Service summary is here: Litigation Weekly January 08 2021 Email

The bullets here include links to court documents.

COURT DECISIONS

Cottonwood Environmental Law Center, v. Bernhardt (D. Montana) – On December 10, 2020, the District Court of Montana issued an order that directed the Department of Interior, National Park Service, and Forest Service to conduct an additional NEPA analysis of the Interagency Bison Management Plan for bison leaving Yellowstone National Park.

(Blogger’s note: This plan and management of bison on the Custer-Gallatin National Forest has also been an issue during its forest plan revision.)

Western Watersheds Project v. USDA APHIS (D. Idaho.) – On December 11, 2020, the District Court of Idaho granted Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service’s request to dismiss the case against APHIS for failure to sufficiently analyze the environmental impacts of their predator control activities in Idaho and the operation of the Pocatello Supply Depot.

(Blogger’s note: While the alleged actions of APHIS were not reviewable, there were also claims against the BLM and Forest Service, which authorized APHIS’s aerial gunning of coyotes and other wildlife on federal lands. The summary does not mention the disposition of those claims or whether they remain pending.)

Cottonwood Law Center, v. Marten, et al. (D. Mont.) – On December 17, 2020, the District Court of Montana granted the Agency’s Motion to Dismiss regarding new information pertaining to the 1987 Custer Gallatin National Forest Plan and the Bozeman Municipal Watershed, North Hebgen, North Bridgers Projects on the Custer-Gallatin National Forest.

(Blogger’s note: One of the claims rejected was that the announcement of forest plan revision constitutes new information that should be considered pursuant to NEPA with regard to the existing forest plan or proposed or ongoing projects.)

WildEarth Guardians v. U.S. Forest Service (D. Idaho) – On December 23, 2020, the District Court in Idaho denied the Forest Service motion to dismiss the case’s remaining claim for reinitiating consultation based on take of grizzly bear resulting from black bear baiting for hunting in national forests in Idaho and Wyoming.

NEW CASES

Alliance for the Wild Rockies v. Marten (D. Mont.) – On December 11, 2020, AWR and Native Ecosystems Council filed a complaint in the District Court of Montana against the Forest Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service challenging the Stonewall Vegetation Project and Forest Plan Amendment #35 on the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. The plaintiffs’ claims relate to new information, including effects of the Park Creek Fire that affected the project area (which was discussed here). (More on the plaintiffs’ perspective, especially on elk, may be found here.)

(Blogger’s note: With regard to this project-specific amendment, plaintiffs challenge the “practice of issuing successive site specific amendments to evade the analysis of what is actually a significant Forest Plan amendment.” While this issue of “cumulative amendments” has been raised under the 1982 planning regulations (unsuccessfully, as I remember it), under the (amended) 2012 Planning Rule a “significant amendment” under NFMA is now one that requires preparation of an EIS, which was the case for this project – “except for an amendment that applies only to one project or activity.” And the 2012 Planning Rule adds no “analysis” requirements for such amendments, though NFMA may.)

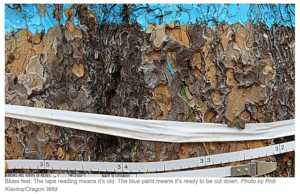

Blue Mountain Biodiversity Project v. Shane Jeffries (D. Or.) – On December 11, 2020, the plaintiff filed a complaint in the District Court of Oregon against the Forest Service, concerning the Walton Lake Restoration Project on the Ochoco National Forest and associated project-specific amendment to the forest plan. This project was previously enjoined but the contract for logging has remained in effect. (More about the area and the project may be found here.)

(Blogger’s note: This complaint also alleges that the project-specific amendment is significant under NFMA. In contrast to the Stonewall project above, an EIS was not prepared here. Under the agency Directives for the 1982 planning regulations there were criteria that determined an amendment’s significance, but those no longer exist. Now the only criterion in the Planning Rule is the existence of significant environmental impacts requiring preparation of an EIS.)

Alliance for the Wild Rockies v. U.S. Forest Service (E.D. Idaho.) – On December 16, 2020, AWR, Yellowstone to Uintas Connection and Native Ecosystems Council filed a complaint in the Eastern District Court of Idaho against the Middle Henrys Aspen Enhancement Project on the Caribou-Targhee National Forest, which used the categorical exclusion for timber stand and wildlife habitat improvement. It includes claims of failure to comply with the forest plan.

In addition, plaintiffs filed a notice of intent to sue the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service under ESA, dated December 14, 2021. Issues include the need to reinitiate consultation on the forest plan because grizzly bears are newly present in the area. (This article provides plaintiffs’ perspectives.)

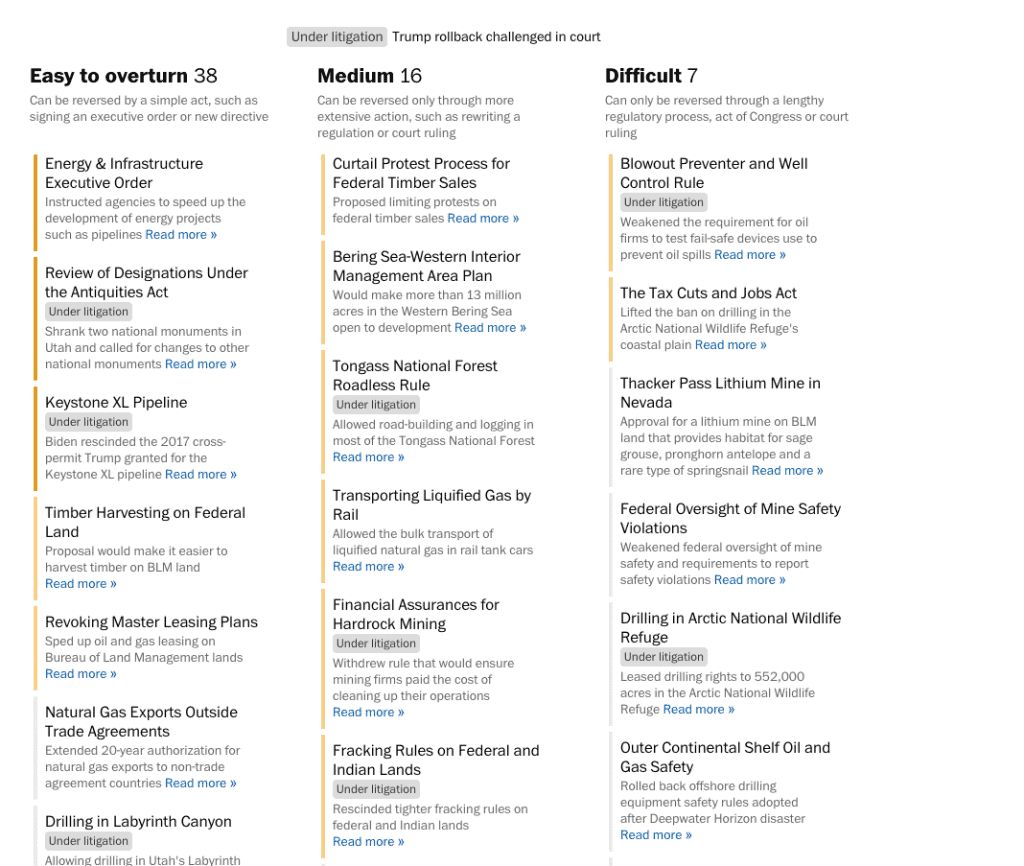

Organized Village of Kake v. Perdue (D. Alaska) – On December 23, 2020, five Alaska native tribes, small businesses, and more than a dozen conservation organizations filed a complaint in the District Court of Alaska against the Department of Agriculture and the Forest Service concerning the 2020 Exception that exempts the Tongass National Forest from the Roadless Area Conservation Rule. (We have discussed this several times, including recently here, and more background is provided in this article.

NOTICE OF INTENT

- Middle Henrys Project (see above)

The Forest Service, BLM and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service received a 60 Day Notice of Intent to Sue, dated December 22, 2020 from the Alliance for the Wild Rockies and Native Ecosystems Council pursuant to the Endangered Species Act regarding the Castle Mountain Project on the Helena Lewis & Clark National Forest and its effects on whitebark pine.

(Blogger’s note: Whitebark pine was proposed for listing as a threatened species on December 2, 2020. The news release from the Fish and Wildlife Service is here, and states, “White pine blister rust, a non-native fungal disease, is harming native whitebark pine trees across the American West. Mountain pine beetles, altered wildfire patterns, and climate change are all negatively affecting the species’ health.”)

BLOGGER’S BONUS (links are to news articles)

(Update.) This litigation concerns the Bridger-Teton National Forest’s decision to reauthorize cattle grazing on 170,000 acres of the Upper Green and Gros Ventre rivers, for which the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service approved incidental take of up to 72 grizzly bears over the following decade, as we discussed here. The District of Columbia district court granted intervenors’ request to transfer the case to the district court in Wyoming, saying, “this case is decidedly a more local controversy than a national one.”

(Court decision.) In its 2014 petition, the Center for Biological Diversity asked the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to update its recovery plan and add several new areas of historic grizzly bear range as potential recovery areas. In a 2011 status review, the wildlife service had said areas in Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, Oregon and southern Washington should be evaluated for their potential for grizzly bear recovery areas, but then the agency declined to include them.

Plaintiffs were denied standing to sue. “A court may review a recovery plan to the extent that it is missing one of the required plan components,” the court order states, “but it may not entertain disagreements with the agency concerning the substance of those components.”