It’s fortuitous that we have this recent example of how a court viewed a population model for an at-risk wildlife species that addresses climate change. The court included the usual caveat that, “Deference to the agency “is especially strong where the challenged decisions involve technical or scientific matters within the agency’s area of expertise.”

It is undisputed that the Service attempted to estimate the effects of climate change by using both “moderate” and “severe” predictions of expected effects, and that for the severe model, it “increased the risk function over time by 20 percent for the 2040 forecast and 40 percent for the 2080 forecast.” 79 Fed. Reg. at 59,147–48. The Plaintiffs take issue with the Service’s observation that the differences in results from the moderate and severe climate change models were “not particularly large.” Disbelieving that this could be a correct conclusion, the Plaintiffs thus suggest that the models “are driven by the Service’s assumption that climate change will have relatively little influence on the threats to individual Trout populations.” (# 76 at 26.)

But the Plaintiffs’ argument begs its own question, assuming that the Service’s models are infected by false preexisting assumptions that climate change effects with be minimal. It is essential to note that the Plaintiffs have not gotten “under the hood” of the Service’s models and pointed out any methodological, programming, or data entry flaws with them. Rather, the Plaintiffs simply argue that the models must be flawed because they produced results with which the Plaintiffs disagree. It may be that the models are flawed, but it may also be that that Plaintiffs’ (and the Service’s as of 2008) expectations about climate change effects are misplaced. Ultimately, it is the Plaintiffs’ burden to demonstrate an error in the Service’s actions, and simply pointing out that two different methodological approaches to calculating the effects of climate change in the far future produced two different results, one of which the Plaintiffs disagree with, does not suffice to carry that burden.

The threatened inquiry takes a longer-term view, asking whether the species might become endangered in a more distant future. But the threatened inquiry is necessarily closed-ended; once the Court has reached the endpoint of the “foreseeable future” (a term found in ESA, and defined recently by regulation) — which the parties here agree is 2080 — the Court’s ability to prognosticate must also come to an end. After 2080, nothing can be foreseen, all is simply speculation. So it is meaningless to ask whether a species will be threatened as of 2080, because it is impossible in 2080 to engage in the long-term future examination that the threatened analysis requires. By 2080, a species must have either reached the level of endangered and be at immediate risk of extinction, or it never will.

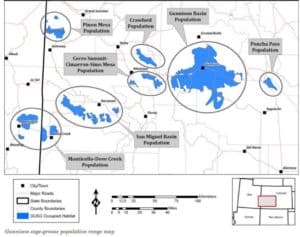

As the Plaintiffs observe, it appears that the Trout is on a “slide towards extinction.” (# 76 at 35.) But if the Service’s models are correct — and in the absence of a challenge, the Court must assume that they are — that slide will not be completed as of or immediately following 2080. At that time, there will still be 50 populations of Trout remaining, a number that the Service believes (and the Plaintiffs have not disputed) is enough to ensure the species’ survival through some indeterminate point in the future. What might become of those 50 populations after 2080 is beyond our ability to foresee; the curtain has come down and the movie has ended. We could attempt to speculate about what might happen thereafter — the 50 populations could persist, they could perish, new populations could be discovered, old habitats could become viable again — but speculation is all it would be. Our ability to predict what might happen has come to an end.

This analysis and decision actually has some important implications for forest planning (from the 2013 Rio Grande Cutthroat Trout Conservation Strategy).

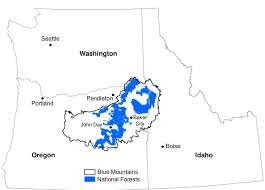

Of the total 1,110 km (690 mi) of occupied habitat, 698 km (434 mi) (63 percent) are under Federal jurisdiction, with the majority (59 percent) occurring within National Forests (Alves et al. 2008).

Range-wide, a large proportion of the watershed conditions within the forests that have Rio Grande cutthroat trout are rated as “functioning at risk,” which means that they exhibit moderate geomorphic, hydrologic, and biotic integrity relative to their natural potential condition (USFS 2011)

Land management activities are currently practiced according to the Carson, Santa Fe, and Rio Grande National Forest Land and Resource Management Plans, and BLM Resource Management Plans. During scheduled revisions, the forests and BLM field offices will evaluate the current Land and Resource Management Plans and update as necessary to provide adequate protection for Rio Grande cutthroat trout with current best management practices. Land management activities that would result in the loss of habitat or cause a reduction in long-term habitat quality will be avoided.

If the trout is a warranted for listing (even if precluded by higher priorities), it is a “candidate” species under ESA. The Planning Rule requires that forest plan components conserve candidate species (which under ESA means the same thing as recover). Since this decision that listing is no longer warranted was reversed, that should mean the species is again a candidate species.

Of course, national forests where the trout is found have been revising their forest plans after 2014, when listing was no longer considered warranted. Consequently, the Rio Grande cutthroat was considered for inclusion as a species of conservation concern. The Rio Grande National Forest has identified the species as an SCC in its final plan (currently in the objection period). The requirement for forest plans for SCC is for plan components to maintain a viable population.

Logically, a species that is warranted for listing should warrant greater protection than one that is not. So it’s possible that the Rio Grande will need to reconsider plan components in areas that are important to this species, or to at least document why this change doesn’t make a difference.

Which could bring us back to the modeling question – how does the Forest Service show that it is meeting the NFMA requirement to provide ecological conditions necessary for this species? If there is a working population model for a species, then those factors that may be influenced by national forest management should be examined to determine how they could change as a result of forest plan decisions, and whether or how that could affect the model results.