A recent High Country News story talks about housing developments on public land.

The U.S. government owns 49% of the land in the 13 Western states, including Hawai‘i and Alaska, according to Headwaters Economics, a nonprofit research group based in Montana. (And that’s not counting all the land owned by the states, municipalities and the military.) In the remainder of the country, the feds own just 3.5%.

At the same time, the West is also experiencing a severe housing crisis: Seven of the 10 states with the greatest housing shortages are on this side of the country.

It’s not surprising, then, that the region’s combination of limited housing supply and vast tracts of undeveloped land has prompted the question: Could building on public lands help ease the housing crisis? From Colorado to California, politicians, academics and housing advocates are trying to find the answer. Here’s what you need to know.

***

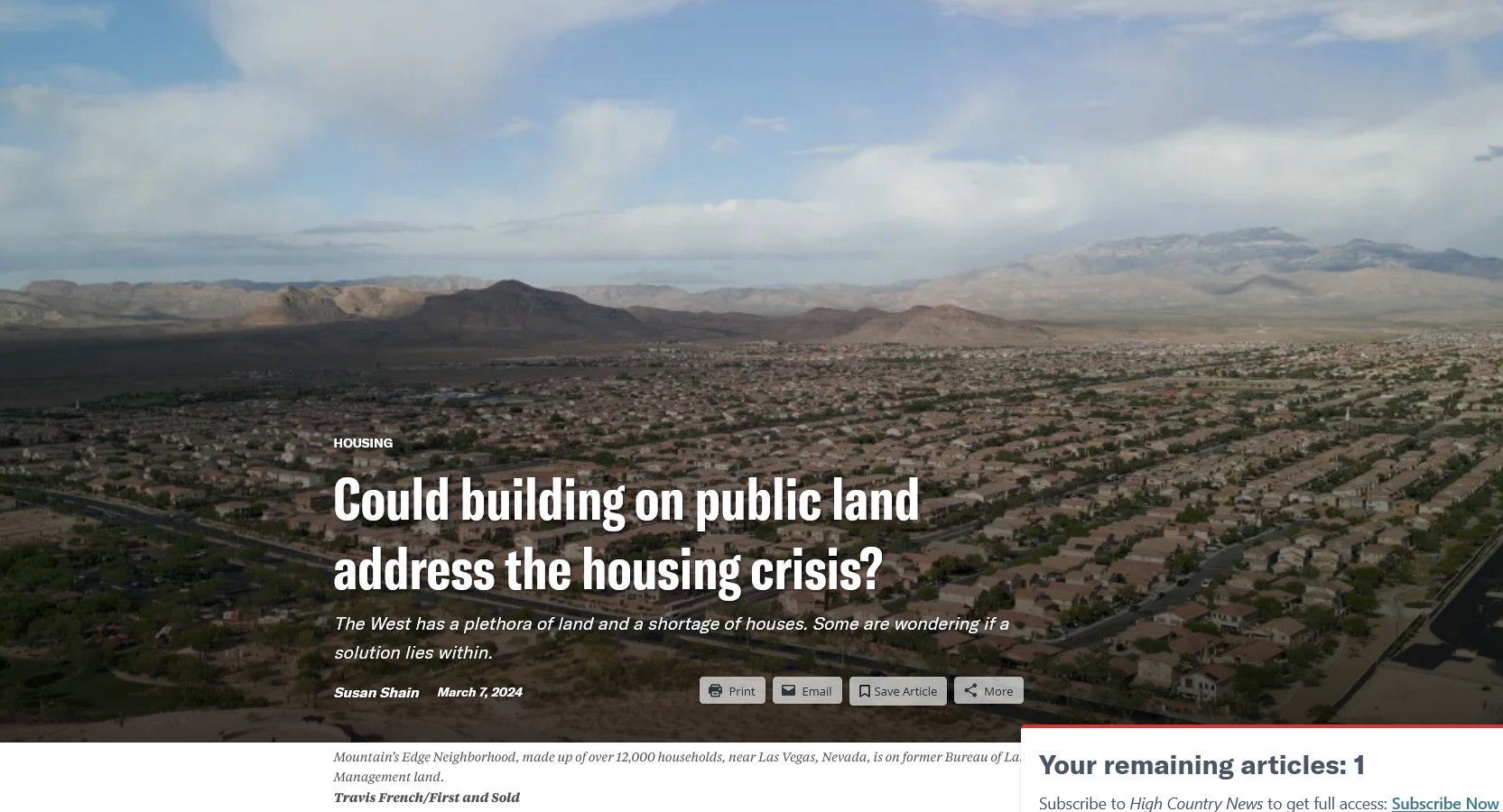

Projects on federally owned land: These can occur when a federal agency, such as the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), sells, leases or trades parcels of land for development. Due to the nature of federal holdings, these parcels are more likely to be on the outskirts of communities. In Nevada, for instance, the BLM has been selling land around Las Vegas to local developers since 1998, with profits flowing back into the state; a new bill could open up nearly 16,000 additional acres of land, most of it federally owned, for housing around Reno.

Lawson said we have two choices: Either build more densely on already available land, or open up new areas for development. The latter option, she said, is particularly pertinent in urban areas where land is scarce, and in rural communities that are surrounded by public lands. Teton County, Wyoming, for example, where Jackson is located, is 97% public lands.

In scenic places like Vail, Colorado or Bozeman, Montana, often referred to as “gateway” communities, Rumore said that increasing the housing supply doesn’t necessarily result in affordability. “If you build more housing and your community is a very popular place to visit, then often that housing gets consumed by short-term rentals” or second homes, she explained. Unless new projects are “very carefully protected for the local workforce,” Rumore fears they won’t make a dent in the housing crisis.

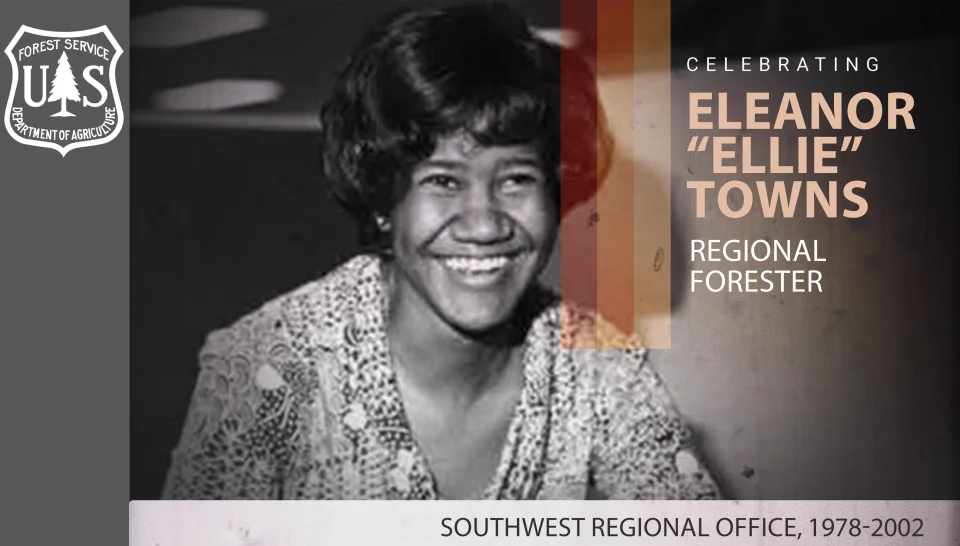

Lawson, the Headwaters economist, agrees, saying that it’s crucial for projects to explicitly tackle affordability. She is optimistic about one in Colorado, where the U.S. Forest Service leased a parcel of land to Summit County to build housing for middle-income earners, such as teachers and firefighters.

On the other hand, Lawson isn’t a fan of efforts that fail to guarantee affordability, such as the HOUSES Act sponsored by Utah Republican Sen. Mike Lee. Research supporting the bill suggests that just 0.1% of the West’s federal lands could provide space for 2.7 million new homes. But the lack of affordability provisions in Lee’s bill has led some critics to call it the “McMansion Subsidy Act.”

While affordability is paramount, Lawson noted a few other factors to keep in mind.

The local economy: In areas like Jackson or Moab, where nearby public lands drive tourism, Lawson warned against developing any land whose loss could negatively impact the local economy— either by removing recreational areas or creating sprawl that detracts from the town’s appeal. As she put it, “It’s very difficult to undo these decisions.”

Infrastructure: When deciding whether a piece of land is worth developing, Lawson recommended examining the existing infrastructure. Are there water lines nearby? What about roads? If infrastructure is lacking, she said, residents need to understand that the cost of building it will likely fall on their shoulders.

Hazards: Communities should also ask whether building on a particular plot will increase the risk from natural hazards, especially wildfire.

Overall, Lawson believes housing projects on public land make a lot of sense when they’re close to towns and existing infrastructure. “It helps communities build more densely within their existing footprint,” she said. “Where I get concerned is when the parcels being talked about are on the fringes.”