Here’s a press release.

Here’s a press release.

The commission will prepare a report with policy recommendations and submit them to Congress within a year of its first in-person meeting in August. A virtual introductory call is scheduled for this month. The Departments of Agriculture, the Interior and FEMA will provide support and resources to assist the commission with coordination and facilitation of their duties.

The commission’s work will build on existing interagency federal efforts such as the Wildland Fire Leadership Council and the White House Wildfire Resilience Interagency Working Group and will continue to pursue a whole-of-government approach to wildfire risk reduction and resilience. It’s creating comes at an important time as shifting development patterns, land and fire management decisions, and climate change have turned fire “seasons” into fire “years” in which increasingly destructive fires are exceeding available federal firefighting resources.

The roster is here.

**************************************

From Sharon:

Bill Gabbert of Wildfire Today has some thoughts on the new Wildfire Commission appointees.

Bill is interested in people with on-the-ground experience as firefighters, he found one but thinks there are probably others. Not to wax all epistemological here, but what does it mean to know about things? It seems that perhaps “knowing” in this case is often “writing about” but not direct experience. When mechanisms need to be set in motion to do things, it seems to me that all things need to be considered at all levels. Otherwise we writers, politicians and the vast array of internet-enabled pontificators can ramble on about things that are fundamentally undoable, or miss obvious things that screw up our best-laid plans. How best to ensure that they don’t “gang aft agley“? Considering more voices from all places. Hopefully that will happen somewhere in the process, perhaps an open public online time for ground-truthing.

A government official who is not authorized to speak publicly on the issue said the makeup of the commission “Has been close hold between fire leadership and intergovernmental affairs. Need to know basis; tighter than budget issues or executive orders.”

The members have their work cut out for them, already up to seven months late on mileposts. Their appointments were to be made no more than 60 days after the date the legislation became law, which works out to January 14, 2022. Their initial meeting was to be held within 30 days after all members have been appointed — no later than February 13, 2022. They are to meet at least once every 30 days, in person or remotely and will serve “without compensation” but can be reimbursed for travel expenses and per diem.

The Hotshot Wakeup Person (HWP) also has some thoughts about the Commission on this podcast at 28:56. He has more concerns that whatever they come up with will be implemented than I do. It seems to be there is plenty of politics between the Commission coming up with ideas and the Congress implementing them.

One of the questions is about “streamlining environmental reviews” or some such thing and I didn’t know anyone I recognize on this on the commission.

I used to count the number of females on commissions (HWP has noticed that females seem to be overrepresented in this group) and so on, but lately have been counting the locations of folks- I’m interested in representation of those impacted, which for wildfires tends to be in the western US, and I’d go so far as to say the “dry forest” part of that west (not, say, the Bay Area, for the most part). Here’s what I came up with:

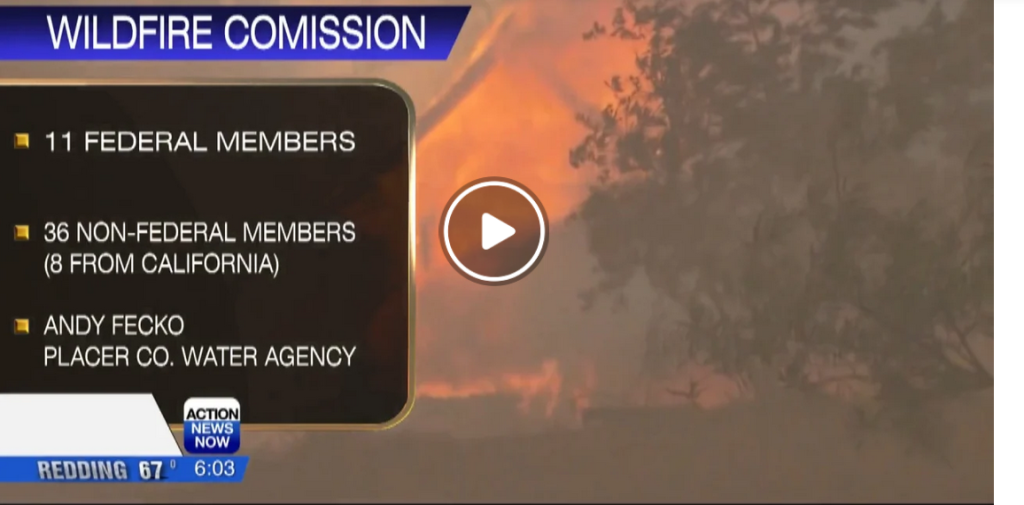

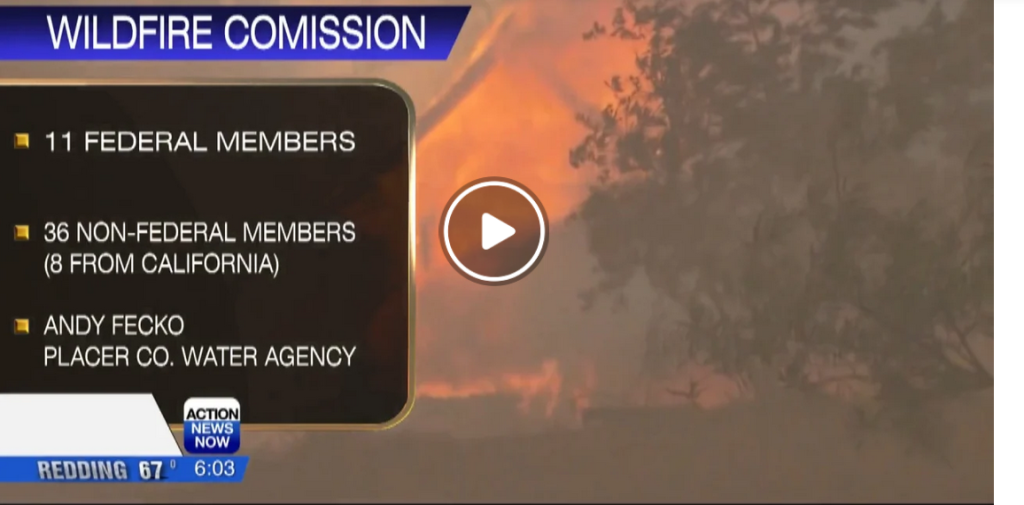

11 DC federal folks.

Az 2

CA 10

CO 5

DC 1

ID 1

MA 1

MT 2

NC 2

NM 1

NV 1

OK 1

OR 3

OK 1

WA 3

Others can check my counting, but it looks like a possible DC/CA show.

Points I like: Of the two scientists, one is a social scientist.

Points I am not keen about:

*Forestry and forest industry as a category. Forestry is a profession, forest industry is a business. It’s kind of like having a category that says “doctors and health care providers” and having hospital businesspeople on the list. Of course, I think getting someone from the ITC is good, but still.

*Forest Stewardship and Reforestation

Sam Cook, Executive Director of Forest Assets & Vice President, NC State University Natural Resources Foundation, NC

Brian Kittler, Senior Director of Forest Restoration, American Forests, OR

From my experience, reforesting dry forests is a tough learning and tech transfer effort which we slowly accomplished in the 80’s at least in the drier parts of Region 6. Oh, and you also need nurseries. I would have selected someone with at least some time in the trenches of doing it (perhaps echoing Bill Gabbert and HWP re:firefighting). I don’t know why they picked these particular folks but it feels more like assuaging interests than developing policy and practices coordinated from the ground to the sky. Which is of course what some of us have pointed out about current policies.. lack of integration and cohesion across governments and communities.

**********************

Given all that, I know there are good people on the panel, and I hope they reach out somehow to the rest of us for ideas and comments.