Three letters in the Helena Independent Record, presented in order of publication. Thanks to Nick Smith for pointing them out.

In Garrity’s letter, he says, “Last year the Forest Service [Region 1] received no bids on 17.5% of the timber offered, up from 15.6% that received no bids in 2018. That’s 615 million board feet that weren’t cut in 2019 because the timber industry did not bid on it.”

Altemus replies that “This is a gross distortion of the facts.”

Anyone know the facts?

Also, timber sales may get zero bids for many reasons — too far from a mill, poor or undesirable species, unfavorable terms, and so on — that have little to do with a region’s overall timber supply.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Public loses on federal timber sales

MIKE GARRITY, Feb. 14, 2020

When Idaho billionaire Ron Yanke purchased the timber mills in Townsend and Livingston years ago to form RY Timber, he also bought lots of former Anaconda Company timberland. But just like Champion International and Plum Creek Timber who, according to a University of Montana study, cut trees three times faster than they could grow back, RY has already overcut their private land.

Both Champion and Plum Creek are gone from Montana, but at least Champion was honest about why it left, stating in the Wall Street Journal in the early 1990s that trees simply grow too slowly in Montana. Champion then clearcut its timberlands and reinvested the money in the Southeast, where tree farms can be harvested a decade after planting rather than the century or more it takes to reach harvestable size in Montana.

Plum Creek did the same thing, thanks to a board decision to “liquidate” its forest assets in the late ’80s and turn itself into a real estate investment trust to sell its marketable Montana lands for subdivision and development as Weyerhauser acquired its mills.

In spite of this sad but well-documented history of timber operations in Montana, RY is blaming environmentalists for what they claim is an insufficient supply of timber from national forests. The basic economic principles of over-supply and over-production in the timber industry are the real problems.

As Julia Altemus, logging lobbyist and director of the Montana Wood Products Association, told the Missoulian’s Rob Chaney: “There’s been a lot of over-production across the board. We have too much wood in the system and people weren’t building. That will make it tougher for us. What would help is if we could find new markets.”

When Stoltze Land and Lumber Co. cut back its mill production cycle from 80 to 50 hours weekly, manager Paul McKenzie told the Hungry Horse News: “It’s purely market driven… demand for lumber across the country is down… supply has actually been good.”

In fact, the “supply” from national forests is more than just good. Last year the Forest Service received no bids on 17.5% of the timber it offered, up from 15.6% that received no bids in 2018. That’s 615 million board feet that weren’t cut in 2019 because the timber industry did not bid on it. The truth is that Region 1 of the Forest Service, which includes Montana, has increased the amount of timber offered by 141% in the last 10 years and the cost to taxpayers continues to climb to staggering heights.

A report by the Center for a Sustainable Economy found “taxpayer losses of nearly $2 billion a year associated with the federal logging program carried out on National Forest and Bureau of Land Management lands. Despite these losses, the Trump administration plans to significantly increase logging on these lands in the years ahead, a move that would plunge taxpayers into even greater debt.”

Adding to that debt are significant “externalized” costs to the public when new logging roads are bulldozed into unroaded areas. Runoff fills streams with sediment that smothers fish eggs and aquatic insects. More logging also reduces forested habitat for elk, which then seek safety on private lands, resulting in problems from “game damage.”

The Montana timber industry once again wants to rape and run. Just as environmentalists were not to blame for its overcut private lands (which are now filled with stumps, knapweed, and degraded streams) environmentalists should now be lauded, not blamed, for trying to stop such destruction on our public lands.

Mike Garrity is the executive director of the Alliance for the Wild Rockies.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Timber-dependent communities deserve better than what some environmentalists dish out

JULIA ALTEMUS, Feb 27, 2020

Michael Garrity’s Feb. 14 opinion letter was certainly no “Be Mine” valentine. It was dripping of desperation and distorted quotes. Again, the author is either grossly misinformed of the facts or intentionally misleading the public. The author stated that “Last year the Forest Service received no bids on 17.5% of the timber offered, up from 15.6% that received no bids in 2018. That’s 615 million board feet that weren’t cut in 2019 because the timber industry did not bid on it.” This is a gross distortion of the facts. Region One works very hard to not have sales go no bid. Rarely is there carryover timber volume in our Region to the next fiscal year. Other Regions may struggle with “no bid” sales, Region One does not. Michael would have the public believe that Montana’s timber industry is leaving valuable timber volume on the table. Not so!

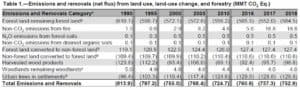

Michael goes on to assert that, “The truth is that Region 1 of the Forest Service, which includes Montana, has increased the amount of timber offered by 141% in the last 10 years and the cost to the taxpayers continues to climb to staggering heights.” The graph, provided below by the U of M Bureau of Business and Economic Research, illustrates that up until the last couple of years, there was a steady decline in federal timber supply, not a 141% increase. [tinyurl.com/ycg53w9j]

At the heart of the decline in harvest and forest health is the fact that Montana is ground zero for litigation. Since the Equal Access to Justice Act (EAJA) was amended in 1988, to allow nonprofits to sue the federal government, Montana has lost 30 mill manufacturers, resulting in the loss of over 3500 jobs.

Region One has paid out $1,204,636.90 in litigation payments under the EAJA to environmental groups in Montana in the past five years alone. No wonder the Alliance for the Wild Rockies has had R-Y Timber in its crosshairs for well over a decade. Dating back to 2007, the Alliance litigated or threatened to litigate 24 of R-Y’s timber contracts equaling over 100mmbf. It’s hard to run a business with a dark litigation cloud hanging over head.

Let’s look at the facts. Currently, Montana’s timberlands are over 63% federal, 23% non-industrial timberlands, 8% industrial timberlands, 5% state, and 1% tribal. Montana’s wood manufacturers must rely on a sustainable and steady supply of raw wood fiber from the federal estate. On average, federal forests in Montana grow 567 million cubic feet annually. At the same time, we lose 510 million cubic feet to mortality, netting 51 million cubic feet of annual growth. We are losing a jaw-dropping 89.9% of our federal forests annually to insects, disease and fire.

Timber harvest is about more than just cutting down trees. There are numerous ancillary benefits. The value of the timber pays for restoration work, brings roads to best management practice standards, improves wildlife habitat, reduces the risk of catastrophic wildfires, provides employment and products that we all use daily.

While environmental groups, like AWR, continue to be engaged in litigation larceny, families, rural timber-dependent communities and the forests they depend upon are suffering.

Julia Altemus is the executive director of the Montana Wood Products Association.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Forest management works best when parties collaborate

CHRIS MARCHION, May 3, 2020

My experiences with Ron Yanke and RY Timber over the past 30 years are substantially different from those characterizations implied by Mike Garrity’s recent letter. I dealt with RY in the 1990s when they purchased former Anaconda Company lands for the purpose of timber harvest.

While I did not agree with all of RY’s harvest decisions, their activities left the land in a condition desirable for public ownership. All of the streams still contain cutthroat and bull trout. The mountain lakes offer quality experiences and much of the landscape is still viable for wilderness consideration and provide critical wildlife habitat. In the late 1990s I worked successfully with Mr. Yanke and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation to put 35,000 acres of these lands into public ownership.

This acquisition took several years of negotiations and payments. Although Mr. Yanke had better offers during the negotiations, he honored his original intent for a public acquisition. Although he was a successful industrialist he had conservation values. I learned he valued his employees, the communities where he operated, and the landscapes he affected. He was an interesting man because he was as comfortable sitting in negotiations involving millions of dollars as he was sitting in a pickup visiting with a logger.

Tragically, Ron died shortly after this acquisition but his company has kept his conservation engagement. In 2019, RY sold an additional 120 acres to be added to the original Watershed purchase.

RY’s recent closure of the Townsend mill which generated comments about environmental obstruction are understandable. Mr. Garrity’s comments as they relate to RY are not. For more than a decade I have been involved in the development of the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge Working Group which is a collaborative of interested forest users contributing to management issues on the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge Forest.

The most urgent forest issue is dealing with over mature lodge pole on forest lands. A major problem has been the inability of the forest to successfully execute sufficient commercial harvest on these lands. Due to a number of factors, including collaboration, timber harvest is up in recent years but still lower than the need dictated by landscape conditions.

We need to do more. The more interest groups involved in the development of these projects, the better the result. The healthier the forest. Obstructing at the end of project development as is Mr. Garrity’s method of legal intervention has not produced a better result. In the 1960s and 70’s international forest corporations were the extreme group promoting timber harvest as the only goal. Those international corporations are gone but Mr. Garrity has replaced their destructive harvests with equally destructive litigation.

Forest management is an evolving science that produces the best results when the interested parties engage constructively in the development of decisions. If Mr. Garrity’s constituents are sincere in their concern for forest health then start by engaging from the beginning of projects. Litigation should be the last resort, not the preferred choice.

Chris Marchion of Anaconda is a member of the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge Working Group and an inaugural member of the Montana Conservation Hall of Fame.