From the Forest Service scoping notice:

The National Forests and Grasslands in Texas (NFGT) is initiating the preparation of an environmental impact statement (EIS). The EIS will analyze and disclose the effects of identifying areas as available or unavailable for new oil and gas leasing. The proposed action identifies the following elements: What lands will be made available for future oil and gas leasing; what stipulations will be applied to lands available for future oil and gas leasing, and if there would be any plan amendments to the 1996 NFGT Revised Land and Resource Management Plan (Forest Plan).

The Forest Service withdrew its consent to lease NFGT lands from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for oil and gas development in 2016. The reason for the withdrawal of consent was due to stakeholder concerns, including insufficient public notification, insufficient opportunity for public involvement, and insufficient environmental analysis. There is a need to analyze the impacts of new oil and gas development technologies on surface and subsurface water and geologic resources; air resources; fish and wildlife resources; fragile and rare ecosystems; threatened and endangered species; and invasive plant management. There is also a need to examine changed conditions since the Forest Plan was published.

These leasing availability decisions are forest plan decisions that were most recently made in 1996. The action proposed by the Forest Service would result in changes in the stipulations and would therefore require a forest plan amendment. The changes would shift about 11,000 acres from “controlled surface use” to “no surface occupancy,” and remove timing limitations from about 35,000 acres.

A letter from five Republican members of the delegation disagrees with the premise that the 1996 analysis was inadequate, and is unhappy with the pace of the amendment process.

The published timeline anticipated a Draft EIS in the winter of 2019 with the Final EIS expected in the fall of 2020. We are concerned that this timeline is no longer achievable given current pace of progress.

We request that USFS end the informal comment period, issue a Draft EIS this spring and ultimately approve the Final EIS that reinstates BLM’s ability to offer public competitive leases of National Forest and Grasslands in Texas for oil and gas leases before the end of 2020. While USFS is required by law to respond to eligible comments received within the public comment window (CFR218.12), the Forest Supervisor also has the authority to declare the available science sound, conclude the public comment period, and proceed with the issuance of the scoping comments and alternative development workshops as the next steps ahead of a Draft EIS (CFR219.2.3, 219.3) (sic).

That last sentence got my attention as the kind of congressional attention to Forest Service decision-making that might cause them to cut a legal corner here or there (especially when there is an election coming). I also noticed the absence of any reference to the new requirements for amendments, and maybe the delay could have something to do with this becoming evident to them as a result of scoping. 36 CFR §219.13(b)(6):

For an amendment to a plan developed or revised under a prior planning regulation, if species of conservation concern (SCC) have not been identified for the plan area and if scoping or NEPA effects analysis for the proposed amendment reveals substantial adverse impacts to a specific species, or if the proposed amendment would substantially lessen protections for a specific species, the responsible official must determine whether such species is a potential SCC, and if so, apply section §219.9(b) with respect to that species as if it were an SCC.

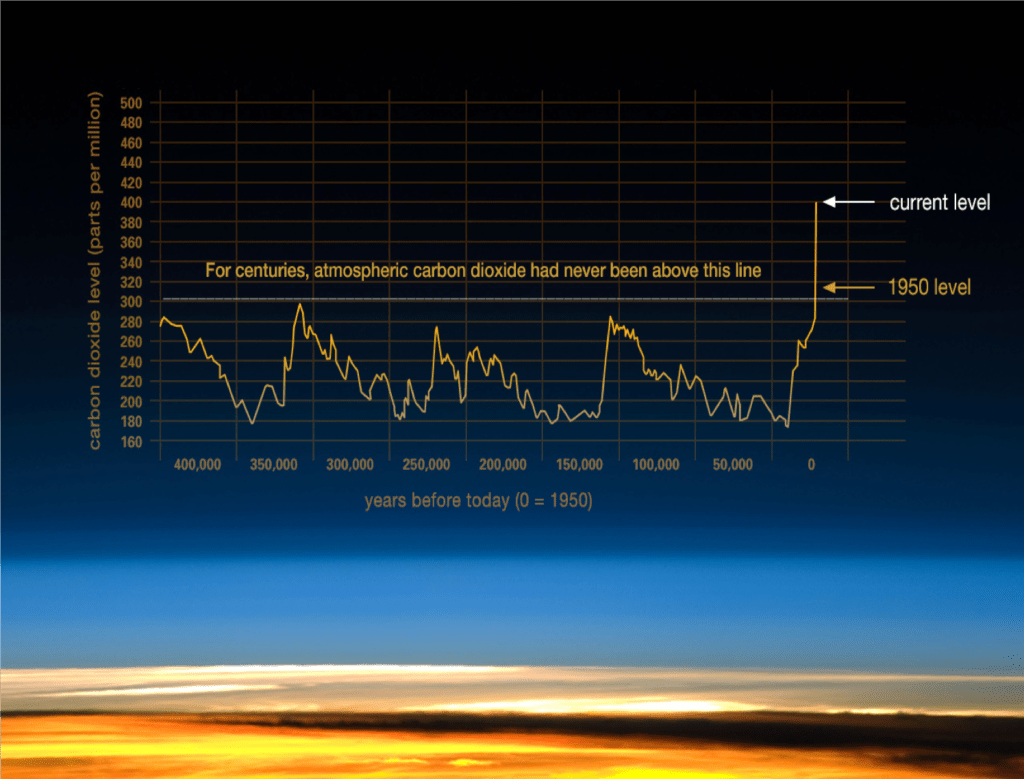

I found nothing in the EIS for the 1996 revision about effects of oil & gas development on at-risk wildlife species. You’d think the new information since 1996 might have something to do with effects on climate change, too.