Having read a few of the “what should we do with carbon in forests” papers, and leaving aside for now the “should we use forest products” discussion, I am thinking that by looking more broadly at forests, carbon, land use change, and other environmental and social factors, we can come back to that discussion with a better sense of context for a variety of climate and carbon interventions.

I’ve found that afforestation and reforestation are on everyone’s list of what can be done that are good for carbon sequestration. Afforestation has a couple of problems. It is land use change, and in many places there are no trees due to the climatic conditions, so it wouldn’t actually work in practice. But in some areas we do have a track record of success..say in the plains states, we could have a 21st century equivalent of shelterbelts (some of the ones from the 1930’s are starting to look pretty ratty).

But back to reforestation (that is, planting trees on forested land post some form of disturbance). We know how to do it in most currently forested places, and used to do it not that long ago (1980’s). In my career, I was fortunate to be involved in the Great Region 6 Reforestation Campaign during which nurseries, infrastructure, technology improvement and so on, were all aligned toward the goal of reforestation. Even Oregon State University had the Fundamental Fir Program. Most people agree with the idea and it is not disruptive to current economic and social structures (such as converting agricultural land to forest). But here’s an angle on it I hadn’t heard before with regard to soil carbon.

Here are some quotes from this Cornell University press release:

The study examined the potential to expand the soil carbon sequestration in reforested areas.

“The ability of U.S. forestlands to offset our emissions of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, is decreasing,” said Hofmeister, who conducts research in natural resources and hydrology. “This is partly due to a backlog in reforestation projects on public lands that has been increasing for several decades.

“Nationwide, since 2000, less than 10 percent of forests are replanted after disturbances that eliminate forest cover. Reforestation would increase the soil carbon sink and go a long way to mitigating climate change.”

..

Sequestering carbon should be a strong component in fighting climate change, according to Hofmeister. “And, unlike other biospheric sinks, such as trees themselves – which can burn up in fires – soil carbon is quite stable,” she said.

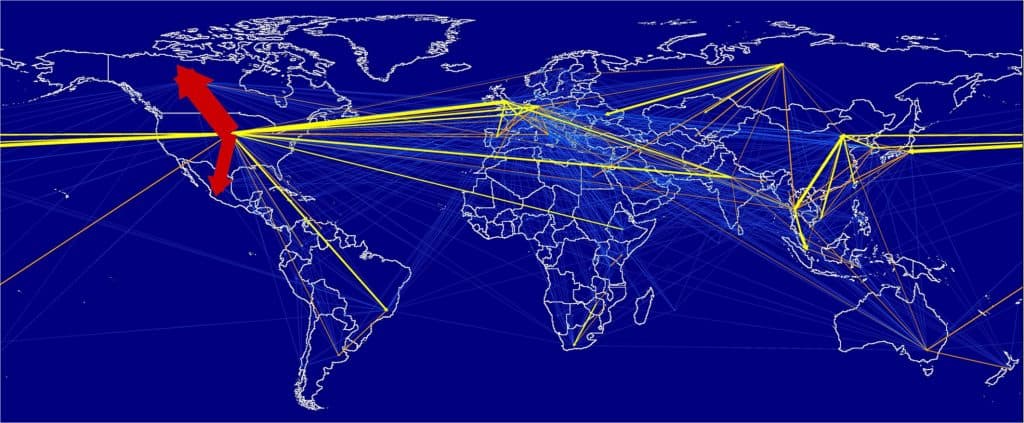

Here is a link to the PNAS paper. You’ll note that the paper is national in scope and used remote sensing. Looking out at your neighboring forest, you would be able to imagine that the numbers for increasing soil carbon locally (over what would happen without intervention) depend greatly on the soils themselves, climate and water availability, the kind of disturbance (think volcano, fire, logging) and how easily (or if) the forest would naturally regenerate. If one were to look at reforesting as a carbon investment and prioritize the areas where you would get the biggest carbon bang for the buck. Still, it’s interesting to think about.