Although there has generally been silence about the potent roles they play, the banking, construction, and real estate industries have excelled at placing human homes and lives in the path of forest fires. At the same time, they have excelled at placing the same homes and people in the backyards of wildlife including, among many others, the grizzly bear. The consequences have been increasingly obvious, but the industries’ role still remains under the radar of many observers.

It would be easy to argue that, at least until recently, these three key industries didn’t know what they were doing, or were at least oblivious to its consequences. But as fires become more fierce and frequent, conflicts with wildlife become more apparent, and officials at all levels of government issuing repeated warnings of risk, it’s getting harder and harder to think that these industries can claim the kind of innocence that comes with ignorance.

It’s also pretty easy to understand that this trio of influential industries can claim, with some justification, that people make their own choices where to live. But it’s just as true that most of the people who move into these fire-prone and wildlife-occupied areas would have a hard time doing it without at least some help from bankers, builders, and the real estate industry.

It seems time for these industries to accept a more positive role. For example, bankers evaluating loans could and should consider whether they are putting money into real estate at risk of burning. This need becomes more pressing if, as seems possible, fire insurance becomes hard to get or costs an arm and a leg to buy. Realtors could also disclose that the land or home a person contemplates buying is in fire-prone terrain. Not doing so leaves unsuspecting customers vulnerable to surprises that they may not want.

Bankers and realtors could and should also advise borrowers that they are buying land in the backyards of, say, mountain lions and bears, or are buying a home already placed in the lions’ and bears’ backyard, and may end up finding the likes of lion and bear continuing to use that land. Here too, not doing so leaves customers vulnerable to problems that they may not expect and certainly don’t want.

These problems clearly leave governments and taxpayers with unwanted costs, most prominently including the increasing cost of defending homes and lives from forest fire. If the banking, building, and real estate industry were held responsible for picking up a fair share of these costs, the Forest Service budget wouldn’t be so badly busted by firefighting expenses.

As things stand now, however, increasing responsibility is being put on homeowners as governments step back. Former Montana governor Brian Schweitzer made it plain that the state budget can’t meet all demand for protecting housing from fire, and that homeowners will have to bear some of the cost themselves. Trouble is, nobody was telling that to the people who populated the fire-prone forests until after the fires drove the point home.

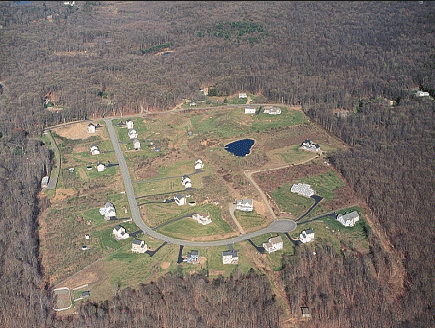

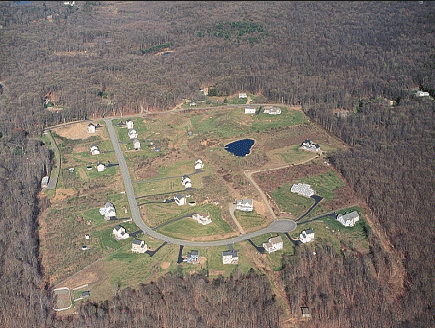

The home-destroying consequence of forest fires, as a recent Rocky Barker column in the Idaho Statesman makes plain, are “not natural disasters.” They are the product of human choices. These choices have been made not only in Idaho, but all up and down the Rockies, and beyond. In Washington, for example, a Forest Service study found that housing development is occupying lands at the rate of a football field every 18 minutes. And fire is just one of many concerns this trend is raising. An author of the Forest Service report said that “People are concerned about losing capacity to grow local food crops and wood products, and about how patterns of development are impacting water quality, wildfire risk, and wildlife.”

The people concerned include the multiple agencies of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee. In IGBC’s recent draft conservation strategy for grizzlies in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, agency biologists identify development as the top source of human-caused mortality in “management removals,” accounting for almost a third of grizzly deaths in the area.

Although they do not explicitly identify the banking, building, or real estate industries per se, biologists do conclude that “The majority of management removals result from conflicts at sites associated with frequent or permanent human presence,” and that grizzlies can be killed for “seeking natural sources of food in areas near human structures.”

Now, it’s plain as can be that a house placed in grizzly habitat can be pretty harmless in and of itself. But when the house is now made home to the likes of chickens, pet food, bird feeders, goats, or anything else a bear will see as something good to eat, and the new homeowner registers a complaint that a bear is showing up, that’s when management removals begin to kick in.

Biologists who prepared the recent grizzly conservation strategy describe sprawl and its consequences as “manageable.” But the management comes at a cost. According to the agencies’ conservation strategy for grizzlies, agencies spend “considerable time and money on outreach actions and materials teaching the public how to prevent conflicts before they occur.”

Ultimately, these costs can be traced back to the sprawl of housing, and can plausibly be calculated as another subsidy for sprawl. If the three industries were held responsible for some share of these costs, state budgets could get some relief from the cost of responding to complaints from the people who move into the backyards of bears, lions, and other wildlife.

Moreover, the effects of such subsidy spill over into streams and rivers. As sprawl brings impermeable surfaces including rooftops, roads, and driveways into natural areas, the denizens of streams and rivers take hits too. And the hits start coming early. In 2012, a USGS study found that streams are more sensitive to development than generally understood, and that the loss of sensitive species in streams begins to occur at the initial stages of development.

A 2010 study in Ecology found that “The loss of natural land to urbanization is one of the most prevalent drivers of novel environments in freshwaters,” and that “Approximately 80% of the declining taxa did so between 0.5% and 2% impervious cover, whereas the last 20% declined sporadically from 2% to 25% impervious cover.”

But of course sprawl brings more than hard, rain-diverting surfaces. It also brings new use of pesticides used by people who want the perfect lawn, or the perfect garden of flowers not native to the landscape. A July 2013 study of pesticides’ impact published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that they can have radical effect on nearby streams, reducing life forms in streams by as much as 42%.

What we may be seeing is that runoff from hard surfaces hastens the pesticides’ progress into streams. But, so far as I know, nobody in banking, building, or real estate is disclosing these impacts to customers who crave a life beside some pretty stream. Likely of even more interest to many customers, though, streamside home construction has direct implications for people, too. Here, think flood, which is becoming much more likely as warming oceans pour more water to the skies. But few if any bankers, builders, and realtors ponder the risks they so willingly create for customers when streamside homes turn into costly nightmare every time a stream or river jumps the banks and brings mud to carpet and flooring.

In fairness, bankers, builders and realtors haven’t been acting alone in delivering unwanted and widely unsuspected consequences to fish, wildlife, and homeowners. Congress and successive Presidents have thrown considerable support to these varied and damaging trends in the form of a Mortgage Interest Deduction which grants homebuyers tax cuts of up to a million dollars in interest payments alone.

This federal largesse is not granted just for primary residences. It is also granted for second homes, even when those homes have been built in our increasingly fire-prone forests, even when those homes are built in the backyards of threatened species such as the grizzly, and, yes, even when they’re built on the permeable soils of important stream and river drainages.

While the banking, building, and real estate industries have prospered in the boon this tax break brings, it would be hard to find a fish or bear that would cheer. For that matter, it would be hard to find much cheer in the hearts of people whose forest homes have gone up in fire, the families and friends of people killed in fire, or any of the victims of pesticide and flood.

Human death has finally forced at least some state governments to act on the risk to life and home brought on by fire. Colorado, for example has set up a task force which, according to a recent article in the Denver Post, may actually suggest “disclosure of wildfire risk before home sales” as a step toward stemming “risks and costs” that have become “too great.”

The Post quotes one Colorado official saying that the homes and lives lost in the Black Forest fire have been “ ‘ a cruel illustration’ of need for a smarter approach.”

Many will be watching to see how much support or opposition bankers, builders, and realtors give to Colorado’s requirement for disclosure of risk from fire. Together, these intimately related industries have high potential to be important allies, or foes, of a smarter approach.

A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision has added some interesting legal intrigue to these issues. At its heart, the Court’s decision was that developers’ rights trump public interest, and that local governments can’t inhibit land development unless they pay developers for any loss thus caused. Given the increasing budget constraints affecting government at every level, the consequence is that developers now enjoy greater freedom from regulation, whether that regulation would protect fish and wildlife from development or people from wildfire. And with this new freedom comes an added dose of responsibility for whatever blood this trio of industries has –and will have — on its hands.

Lance Olsen, a Montana native, was president of the Missoula, Montana-based Great Bear Foundation from 1982-1992. He has also served on the governing council of the Montana Wilderness Association and the advisory council of the Alliance for the Wild Rockies. He was previously a college teacher and associate of the American Psychological Association and its Division on Population and Environmental Psychology, and the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues. Now retired, he runs a restricted listserv of global scope for climate researchers, wildlife researchers, agency staff, graduate students, and NGOs concerned about the consequences of a changing climate. He can be contacted at [email protected]. This article originally appeared at Counterpunch.