A couple of weeks ago, I was on a field trip on part of the old Routt National Forest, when I had to take a climate change conference call. Since cell phone coverage was spotty, we targeted a good spot and I was dropped off for a couple of hours and sat at creekside while on the calls.

Looking at the dead trees on the hills, it became clearer to me some of the disconnects between climate change as talked about or written about in scientific journals, and as currently lived.

1. People are already dealing with climate change every day as part of their work.

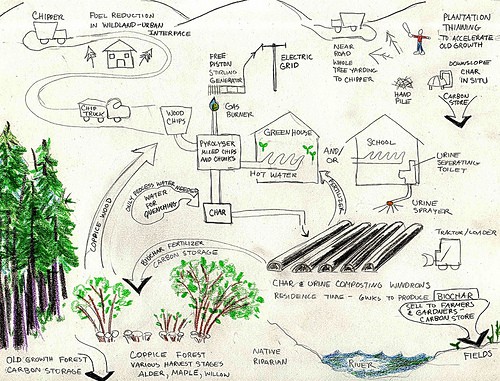

People are felling hazard trees, doing WUI fuels treatments, looking for biomass opportunities, etc. Climate change is just another change agent that affects our work.

2. We may never know how much of what we observe is due to climate change (take bark beetles; 100% climate change? 75% climate change plus the age of trees 25% ?). But we still have to deal with the changes, regardless of their source. So it probably doesn’t make sense to have a separate pot of funds for climate change adaptation or resilience- otherwise we might spend out time in tedious disagreements about whose problem is more climate-induced.

3. We will be dealing with these issues collaboratively, locally (for the most part) using an all lands approach, and involving regulators and communities early and often.

We can’t or shouldn’t get to the point where the community and the FS are in one place, but the regulators have a different worldview.

4. Climate change will include opportunities as well as hazards and difficulties.

For example, at the Steamboat Ski Area, we visited a site where dead trees provided an opportunity for a children’s outdoor ski run.

5. It could be argued that the complex structure of direction in the Forest Service does not make us as flexible and adaptive as we need to be. Changes due to climate change and other factors can occur more quickly, and in different spatial/temporal configurations, than the current structure can easily respond to.

For example, the ranger district or forest is the right scale for many decisions. But not for bark beetles. Should it be dealt with by the current three forests? An interior west scale group? What would be the governance of such a group?

We have the incident command model for fires.. but if something is large, but not a month by month kind of emergency, do we have an organizational structure to deal with it?

6. Safety of our employees and the public need to come first.

I don’t know at the end of the day how many climate change issues will have real safety hazards such as bark beetle and other sources of dead trees. The urgency requires new ways of working together in a timely way. Environmental groups, industry groups, local communities, regulators- we all need to be able to speed up from our bureaucratic and legal natural rate of speed to an emergency rate of speed.

7. If ecosystems are too complex to predict (“more complex than we think, more complex than we can think”), let’s use scenarios and not specific predictions, and pick “no-regrets” strategies. I wonder sometimes if we are overthinking and overanalyzing climate changes and I think we should consider the opportunity costs of what we could to to “protect reconnect and restore” in the Trout Unlimited strategy versus “assess, predict and model.” Note that while common sense and decision theory under uncertainty have always argued for “no regrets” strategies, now at least some water scientists agree.

I would ask us to think about that climate change may be a stressor to our organizational and social systems as well as the environment. It requires us to work together faster, and better than we have in the past. I often wonder if climate science funding were divided half to social scientists (with one quarter to business and public administration schools), what would the “best available science” look like?

I’d be curious about others’ ruminations on these topics…