There is an request for comments from USDA that concerns topics of interest to TSW readers, specifically climate-smart forestry. The due date for comments is April 29, 2021. It’s part of Biden’s Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.

I like how comprehensive it is, and the broad range of topics, as well as the questions that directly address what tools and research are needed, and how we can all work together better. I’d be interested in getting guest posts (email me at email on donations link) or comments that describe your own ideas. Also if your organization has sent in a comment, please link below.

I already found some interesting responses in the Regulations.gov site, but it’s kind of a pain to click on every answer, read it, download the document, read it, go back to the site remembering the last name I looked at… If anyone has an easier way of reviewing comments (like tweaking it so it reads them directly into one giant pdf?). Any ideas on how to do this better

would be appreciated.

1. Climate-Smart Agriculture and Forestry Questions

A. How should USDA utilize programs, funding and financing capacities, and other authorities, to encourage the voluntary adoption of climate-smart agricultural and forestry practices on working farms, ranches, and forest lands?

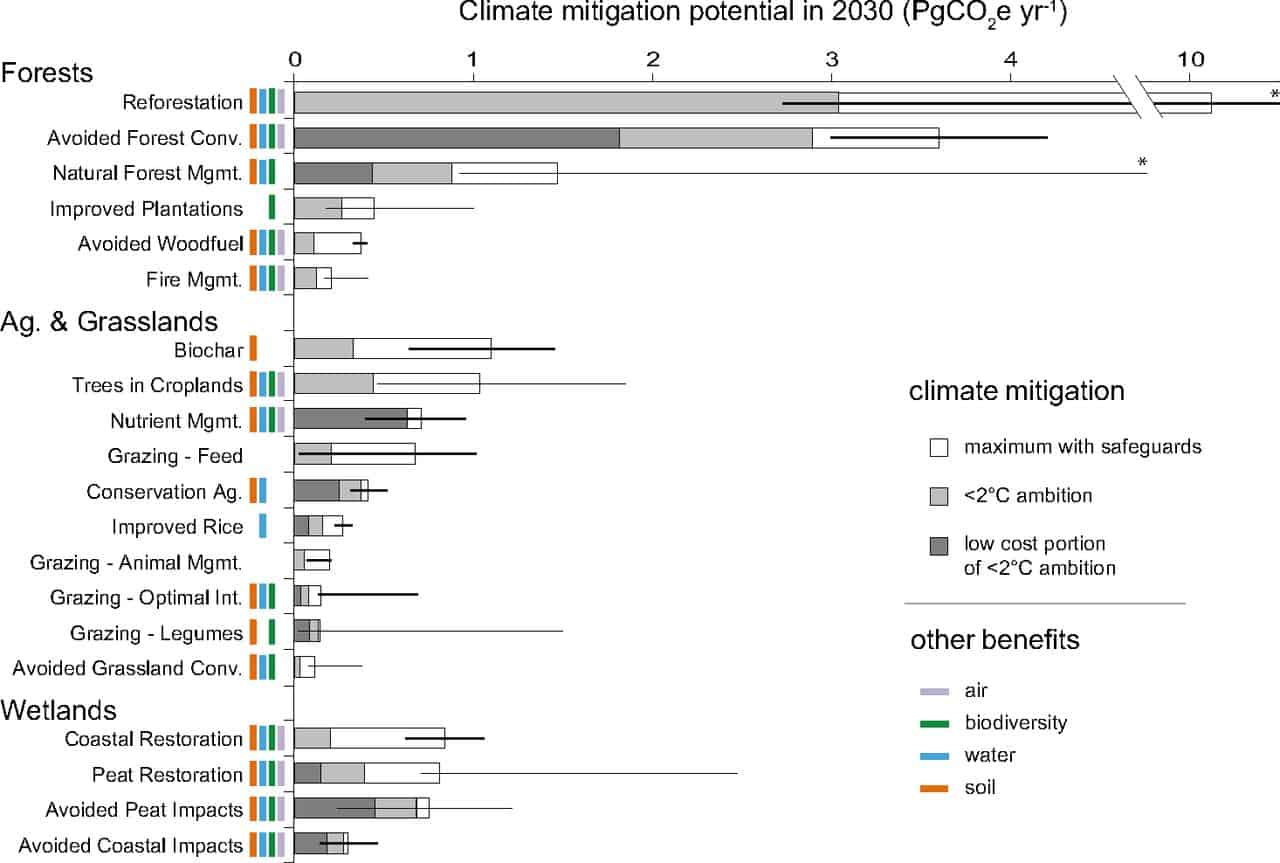

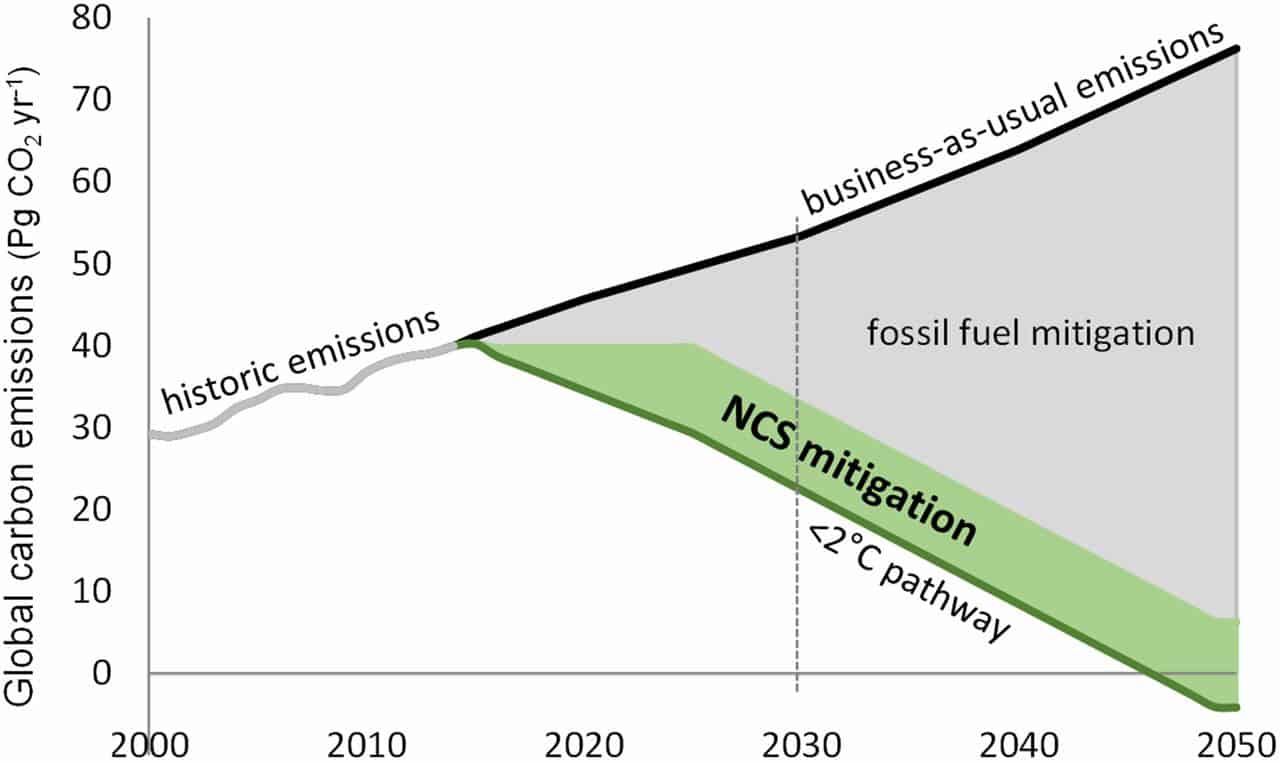

1. How can USDA leverage existing policies and programs to encourage voluntary adoption of agricultural practices that sequester carbon, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and ensure resiliency to climate change?

2. What new strategies should USDA explore to encourage voluntary adoption of climate-smart agriculture and forestry practices?

B. How can partners and stakeholders, including State, local and Tribal governments and the private sector, work with USDA in advancing climate-smart agricultural and forestry practices?

C. How can USDA help support emerging markets for carbon and greenhouse gases where agriculture and forestry can supply carbon benefits?

D. What data, tools, and research are needed for USDA to effectively carry out climate-smart agriculture and forestry strategies?

E. How can USDA encourage the voluntary adoption of climate-smart agricultural and forestry practices in an efficient way, where the benefits accrue to producers?

2. Biofuels, Wood and Other Bioproducts, and Renewable Energy Questions

A. How should USDA utilize programs, funding and financing capacities, and other authorities to encourage greater use of biofuels for transportation, sustainable bioproducts (including wood products), and renewable energy?

B. How can incorporating climate-smart agriculture and forestry into biofuel and bioproducts feedstock production systems support rural economies and green jobs?

C. How can USDA support adoption and production of other renewable energy technologies in rural America, such as renewable natural gas from livestock, biomass power, solar, and wind?

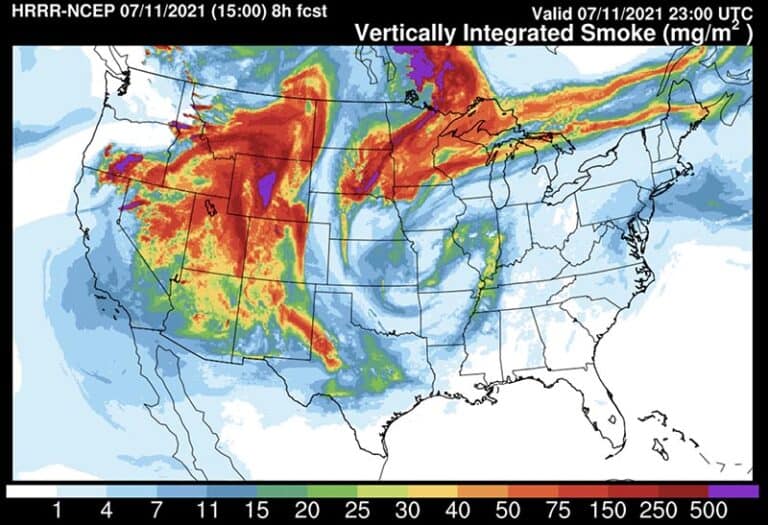

3. Addressing Catastrophic Wildfire Questions

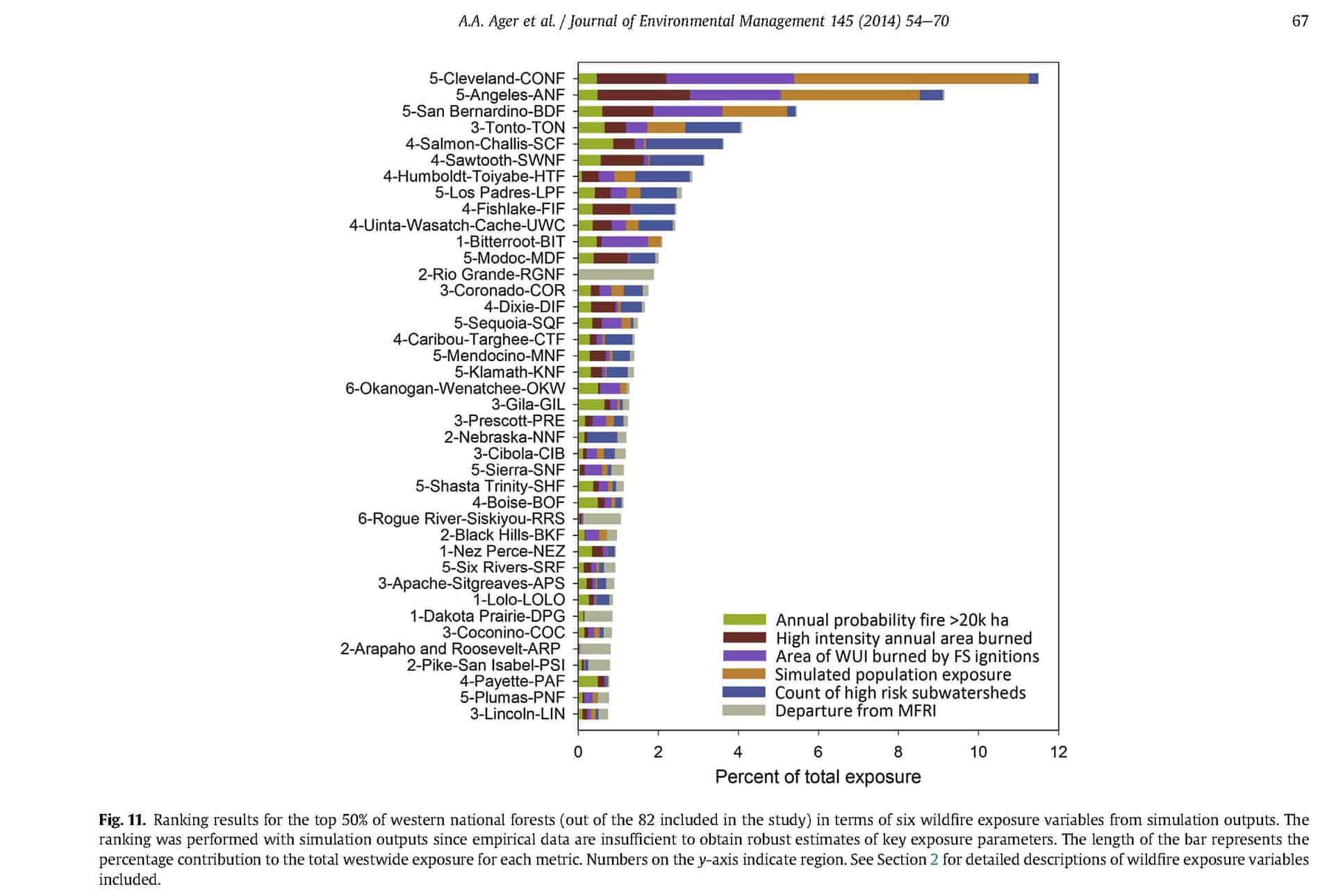

A. How should USDA utilize programs, funding and financing capacities, and other authorities to decrease wildfire risk fueled by climate change?

B. How can the various USDA agencies work more cohesively across programs to advance climate-smart forestry practices and reduce the risk of wildfire on all lands?

C. What additional data, tools and research are needed for USDA to effectively reduce wildfire risk and manage Federal lands for carbon?

D. What role should partners and stakeholders play, including State, local and Tribal governments, related to addressing wildfires?

4. Environmental Justice and Disadvantaged Communities Questions

A. How can USDA ensure that programs, funding and financing capacities, and other authorities used to advance climate-smart agriculture and forestry practices are available to all landowners, producers, and communities?

B. How can USDA provide technical assistance, outreach, and other assistance necessary to ensure that all Start Printed Page 14404producers, landowners, and communities can participate in USDA programs, funding, and other authorities related to climate-smart agriculture and forestry practices?

C. How can USDA ensure that programs, funding and financing capabilities, and other authorities related to climate-smart agriculture and forestry practices are implemented equitably?

Please provide information including citations and/or contact details for the correspondent when submitting comments to Regulations.gov.

Seth Meyer,

Chief Economist, Office of the Chief Economist.