Here are some of my thoughts from the discussion. I know folks on The Smokey Wire (especially Sam Evans) have been very involved, so I’d appreciate any thoughts of your own and corrections.

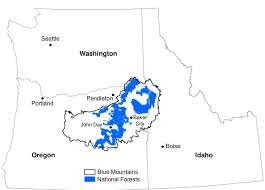

1) While the history of pre-National Forest cultures and livelihoods on the land is generally better known and documented in the east, many of the issues discussed sound similar to parts of the West. They spoke of increasing/recreation, second homes and subdivisions, fire management, and vegetation management including commercial tree removal. Topics like sustainable recreation, increased pressure, and increased visitation are just as difficult in many places in the West.

2) One of the advantages of strategic planning or large landscape planning ideally is that people can work together to find common ground at a broader scale than “this project” or “that problem.” Based on the discussion, and comments by Sam Evans here, that generally seems to be how it is working. One person said that this collaboration might continue into implementing the plan. It did sound as if the forest plan perhaps provided a nexus for discussions and collaboration that otherwise would not have happened, as a “good forest planning process” ought. I am not sure how much of that is due to the Forest Service individuals, to collaborators, or to the unique culture, history and relationships on this land. Would be an interesting social science study to look at the the different forest planning efforts in about 10 more years.

Sidenote: I think we might disagree that, for example, a rancher from Burns, Oregon should have as much say about the Pisgah-Nantahala as someone in the collaborative group, and an insurance agent from Oklahoma who has never been there should have as much say as someone whose family has traditionally used the land for four generations. It’s interesting to think about “who cares about forests that are far away from their home” and why. I didn’t get the impression that this plan has major out-of-area interests, but I could be wrong.

3) Someone on the panel cited a book, Blue Ridge Commons, 2012 book by Kathryn Newfont. Here’s an excerpt from a blurb by University of Georgia:

In the late twentieth century, residents of the Blue Ridge mountains in western North Carolina fiercely resisted certain environmental efforts, even while launching aggressive initiatives of their own. Kathryn Newfont examines the environmental history of this region over the course of three hundred years, identifying what she calls commons environmentalism-a cultural strain of conservation in American history that has gone largely unexplored.

Efforts in the 1970s to expand federal wilderness areas in the Pisgah and Nantahala national forests generated strong opposition. For many mountain residents the idea of unspoiled wilderness seemed economically unsound, historically dishonest, and elitist. Newfont shows that local people’s sense of commons environmentalism required access to the forests that they viewed as semi-public places for hunting, fishing, and working. Policies that removed large tracts from use were perceived as “enclosure” and resisted.

These battles often pitted industrialists against environmentalists. Newfont argues that the side that most effectively hitched its cause to local residents’ commons culture usually won. A few perceptive activists realized that the same cultural ground that yielded wilderness opposition could also produce ambitious protection efforts, such as Blue Ridge residents’ opposition to petroleum exploration and clearcut timber harvesting.

I still don’t see Jane’s Sawmill as “industrial” but.. Perhaps there is an element of “keeping traditional people and uses out” that we also see in closing access in the West (outside of the Designated/Wilderness debate), although the argument is that it’s better for wildlife and the Forest Service can’t afford the upkeep on roads. But I have definitely heard a dislike for reduced access in comments on western forest plans (and travel management). Maybe east and west are not all that different.