“Better to be safe than sorry.”

“Nothing ventured, nothing gained.”

“First do no harm.”

“Fences are made for those who cannot fly.”

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Caution or boldness? What happens if doing nothing is worse? This is one of the debates emerging from the Forest Service planning rule development.

In the 1970s, the Black Forest in Germany was obviously deteriorating. Acid rain associated with sulfur and nitrogen emissions from industrial, commercial, and transportation sources was the suspected culprit, but science could not provide firm evidence of cause and effect. Despite this scientific uncertainty, the German government instituted regulations to reduce power plant emissions. The policy became known as “Vorsorgeprinzip”, which translates into the “principle of advanced caring.” After evolving into a key component of German environmental law, the concept of precautionary action gradually gained wider acceptance across Europe and was incorporated into various international treaties, conventions, and declarations. The concept grew into what is known today as the precautionary principle.

The precautionary principle states that if an action or policy has a suspected risk of causing harm to the public or to the environment, in the absense of scientific consensus that the action or policy is harmful, the burden of proof that it is not harmful falls on those who advocate taking the action. This principle allows policy makers to make discretionary decisions in situations where there is evidence of potential harm in the absence of complete scientific proof. The principle implies that there is a social responsibility to protect the public from exposure to harm, when scientific investigation has found a plausible risk. These protections can be relaxed only if further scientific findings emerge that provide sound evidence that no harm will result.

The principle has become very popular, embraced by governments around the globe. In the European Union, the application of the precautionary principle has been made a statutory requirement. It has been incorporated into many treaties and resolutions, including the Rio Declaration, the Montreal Protocol, the Convention on Biological Diversity, the 1992 Climate Change Convention, the Treaty on European Union, the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic, and the Helsinki Convention on Marine Protection in the Baltic. In 2005, the city of San Francisco, adopted a precautionary principle purchasing ordinance.

At a 1998 conference convened by the Science and Environmental Health Network at the Wingspread House in Racine, Wisconsin, a group of scientists, philosophers, lawyers, and activitists developed a widely-cited consensus statement about the precautionary principle:

When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.

The precautionary principle has been proposed by various environmental groups as a central theme of a new Forest Service planning rule. It became one of the discussion questions during the third planning rule national roundtable last week. But there are questions about the appropriateness of the principle in a typically value-laden forest planning process lacking agreement on goals, and when inaction could be as risky as action.

Although it was only briefly mentioned at the planning rule science forum in the question and answer period for the first panel, it was highlighted in Booz Allen’s summary report of that meeting. Tom Sisk from Northern Arizona University observed that when we lack information we still need to make tough decisions. In order to protect the environment, management should be appled according to the ecosystem capabilities. Sisk said that a lack of uncertainty should not be used to adopt environmental protections. Later, there was a follow-up question from the audience about whether we should be using adaptive management instead of the Precautionary Principle. Sisk reminded everyone that the Precautionary Principle cuts both ways: both taking and not taking action. We should not let uncertainty stop us in our tracks.

Alston Chase has argued that the precautionary principle does not always benefit society, could produce more ecological and social harm than good, with consequences not known until it’s too late. He explains that in “game theory” there is no such thing as a “correct decision” under conditions of uncertainty, and that all choices are subjective, reflecting the values of the decision-maker. When applied to natural resource planning, he argues that it presupposes the idea of a self-regulated ecosystem, seeking to protect conditions that never existed, never will exist, or never could exist.

In the middle of the debate over the use of the precautionary principle in Forest Service planning is the set of Forest Plan amendments comprising the Sierra Nevada Framework. The principle played an important role in the 2001 amendments. However, risk and uncertainty assessment teams in 2003 observed the dangers of applying the principle, and a new decision was made in early 2004. (On separate issues the decision was litigated and a Federal Register notice to supplement the analysis was issued earlier this year).

In 2004, Hal Salwasser, School of Forestry Dean at Oregon State, and former director of the Pacific Southwest Experiment Station, wrote about his experiences with the complex and messy forest planning in the Sierra Nevadas, and the problems he saw with the application of the precautionary principle in these types of “wicked problems” .

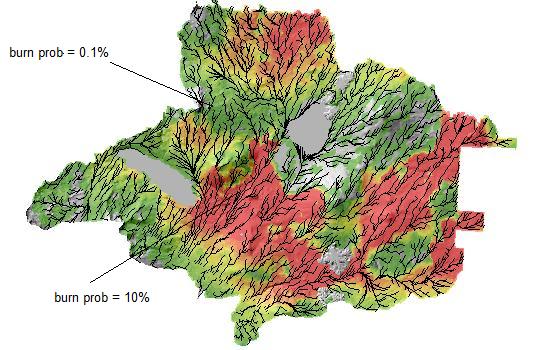

The precautionary principle has several flaws that make it questionable as a guide to decision making (Beckerman 2000). First, if the future is really all that uncertain, then we cannot be confident that action taken or not taken today will not make the future better rather than worse. Second, what constitutes harm is not always clear and could vary over time and space. When the precautionary principle is applied to dynamic ecosystems to constrain actions, such as fuels thinning needed to restore the system’s resilience to fire, it sets up the potential for major long-term harm: harm from inaction could be greater than harm from proposed action. Inaction creates “opportunity benefits,” that is, benefits foregone because action was not taken (Wildavsky 1995).

It is not possible to have full certainty regarding most of the important things in life, and ecosystems are certainly no exception. The standard for burden of proof about certainty in the precautionary principle is infinitely high. And taking no action precludes the opportunity to learn from trial and error. The upshot of applying the precautionary principle is either nothing will ever get done or the preconditions for action are so time consuming and burdensome that action is excessively costly, too timid, or too late. The consequence will be countless unintended harms as a result of inaction. Care, thoughtfulness, and testing of ideas make sense, but extreme precaution is hardly prudent in a dynamic ecosystem, especially one that is vulnerable to uncharacteristic disturbance events. Thus, in situations such as those that confront Sierra Nevada ecosystems, stakeholders, and managers, the precautionary principle sheds no light on prudent choices.

The precautionary principle appears to have greatly influenced how risk or uncertainty about forest management impacts on certain fish and wildlife entered the decision rationale in the 2001 Sierra Nevada Forest Plan Amendment. It appears that uncertainty was assumed to have only negative potential outcomes; however, uncertainty means outcomes or future events are uncertain in both directions. The rationale for how tradeoffs were made warrants open critical thinking and review of what uncertainty implies, what harm is, and how it is judged vis-à-vis other objectives. The 2004 revised Record of Decision handles risk with more boldness, yet even it is insufficient to address the magnitude of risk to late successional forests and their ecological values posed by uncharacteristically intense fires”.

Salwasser adovates decision analysis and adaptive management learning processes used in other disciplines for complex problems (things that have been discussed on this blog).

In the planning rule roundtable meetings, some participants have suggested that the Forest Service develop a framework using experimental approaches with a precautionary underpinning to address forest challenges. But others have noted that forest restoration is expensive and suggested that caution (whether enacted actively or passively) is the appropriate framework to reduce costs in the national forests. Both risks and benefits are apparent in the multiple-use mission of the Forest Service, so this is an important debate.

Environmental lawyer Carolyn Raffensberger, one of the leading advocates of the precautionary principle, has said that it’s about setting goals, reversing the burden of proof, looking for the safest alternative, and emphasizing public health and the environment over economics. But she also concludes that the final element of the precautionary principle is democracy:

If we’re faced with scientific uncertainty, we need to set goals, and choose the safest alternative to achieve these goals. These processes involve values and ethics; it is not something that scientists or government bureaucrats can decide alone. We need to bring affected parties to the table. This gives us a chance as a public to set the goals that we want to drive toward; it helps get on the table a much wider array of options for solving problems and looking for alternatives. So democracy is also an essential component of the Precautionary Principle.”

Perhaps a conversation is a good place to start.