Two of these were originally posted as comments related to other posts and the third I would have, but Sharon intimated that they might not get noticed there, so here they are at the top end of a post.

BATS

We were discussing how the wolverine is most affected by climate change, and yet ESA requires mitigation of other less harmful activities that we have more control over. The effect of an introduced disease on bats also came up there. A federal judge has just overturned a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect northern long-eared bats as threatened rather than endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Here’s the Center for Biodiversity’s read-out of the judge’s opinion (there’s a link to the opinion, but I haven’t read it):

The Service argued that since the species was primarily threatened by disease, there was no need to protect its habitat. But the court rightly noted that, in combination with disease, habitat destruction and other threats can cumulatively affect the bats, and thus are cause for concern.

It’s a point of contention these days whether climate change should be a factor in listing decisions when there is little likelihood of reducing its effects, but the law says it’s important to address and potentially mitigate other actions that may harm the species.

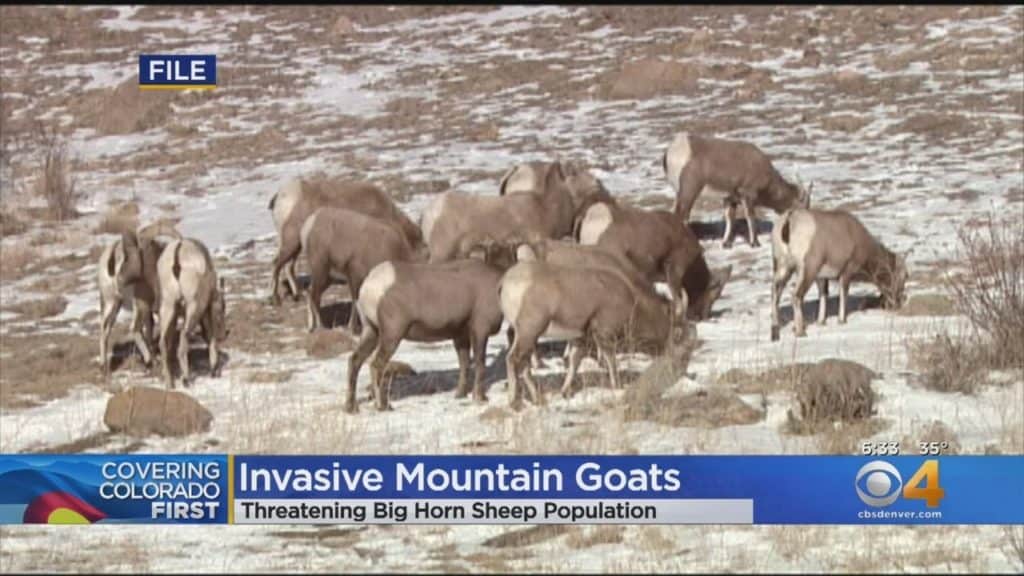

BIGHORNS

The Bridger-Teton National Forest is considering a restocking request for returning domestic sheep to two vacated allotments in the Wyoming Range. It hinges on changing the forest plan to deemphasize protections for the Darby Mountain bighorn sheep herd. This would purportedly be consistent with the State of Wyoming’s bighorn plans. The Forest is proposing to do a “focused amendment” to their forest plan, but …

Bighorn advocates and conservationists who have watchdogged the restocking conversations wanted the Forest Service to instead deal with the issue in its forest plan (revision). The years-long revision process was supposedly coming up, though O’Connor said it’s now indefinitely on hold. Wyoming Wild Sheep Foundation Director Steve Kilpatrick said the Darby Mountain Herd deserves the longer, closer look.

I’m not sure the Forest is going to be able to do a “focused amendment” for this issue, since bighorn sheep should be a species of conservation concern under the 2012 Planning Rule, which warrants greater attention. Maybe this is a case where the inability to revise a forest plan is going to cause some problems. Then there is the question of why these allotments were vacant. The permittees were “bought out” through the efforts of the National Wildlife Federation (to protect bighorns?). Would they need to be paid back?

GRIZZLY BEARS

The discussion of reintroducing wolves to Colorado brought up the experience with grizzly bears in the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness in Montana and Idaho. A reintroduction proposal was rejected in 2001, but at least two bears have been documented there in recent years. Here is the recent news about that. The Fish and Wildlife Service has written to the Forest Service that bears that have made it there are fully protected by the Endangered Species Act (not an experimental population). All four of these forests are revising or will soon revise their forest plans and will have to provide conditions to support grizzly bear recovery. The Nez Perce-Clearwater is farthest along but has been avoiding doing that.

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com

Copyright: Photowitch | Dreamstime.com