Here’s a new paper on PODs. It’s Open Access, so yay! Check it out, lots of interesting stuff.

Here’s a new paper on PODs. It’s Open Access, so yay! Check it out, lots of interesting stuff.

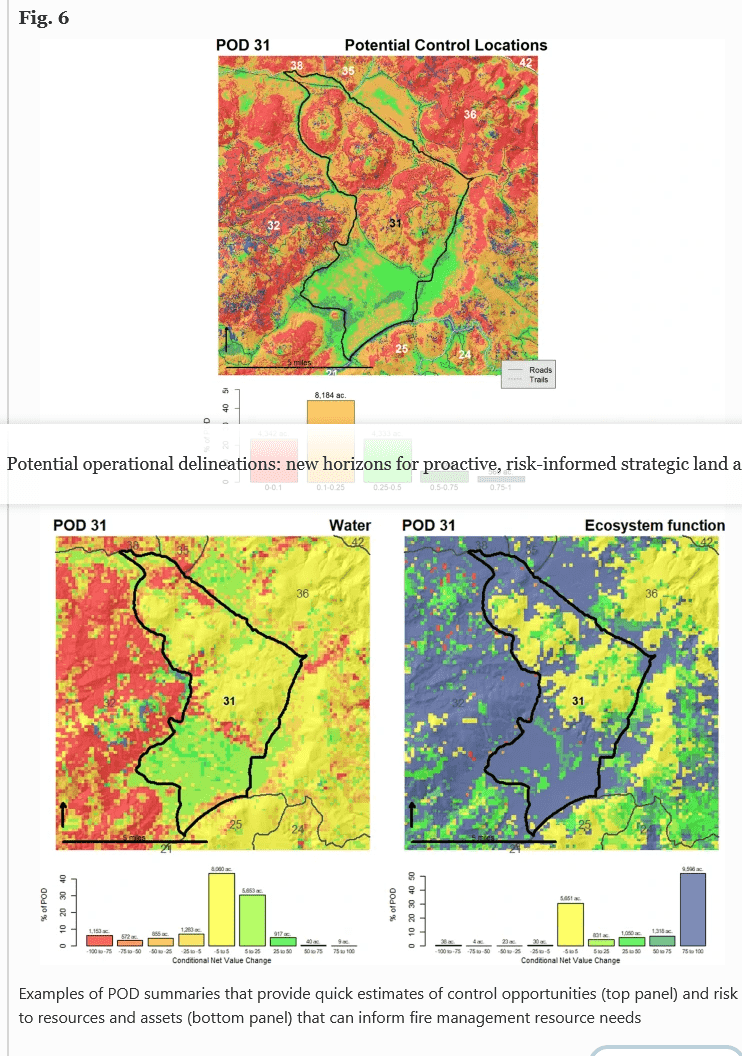

I’m a big fan of PODs’n’PLANNING, that is, I think the FS should put a time-out on plan revisions (after all, now we don’t know where the Mature and Old Growth potential rule will go, which could upend all that) and just do EIS’s for PODs and other fire management related decisions requiring NEPA, including POD maintenance through time. PODs’n’PLANNING would necessarily take into account the resource values (including old growth) that would be desirable to protect from wildfires. Perhaps by putting into the “wildfire management strategies” box we will get away from the old “fuel treatments don’t work; just protect houses” discussion. Note that the protection of water and ecosystem function are included in Fig. 6 below. A girl (even an old lady) can dream…

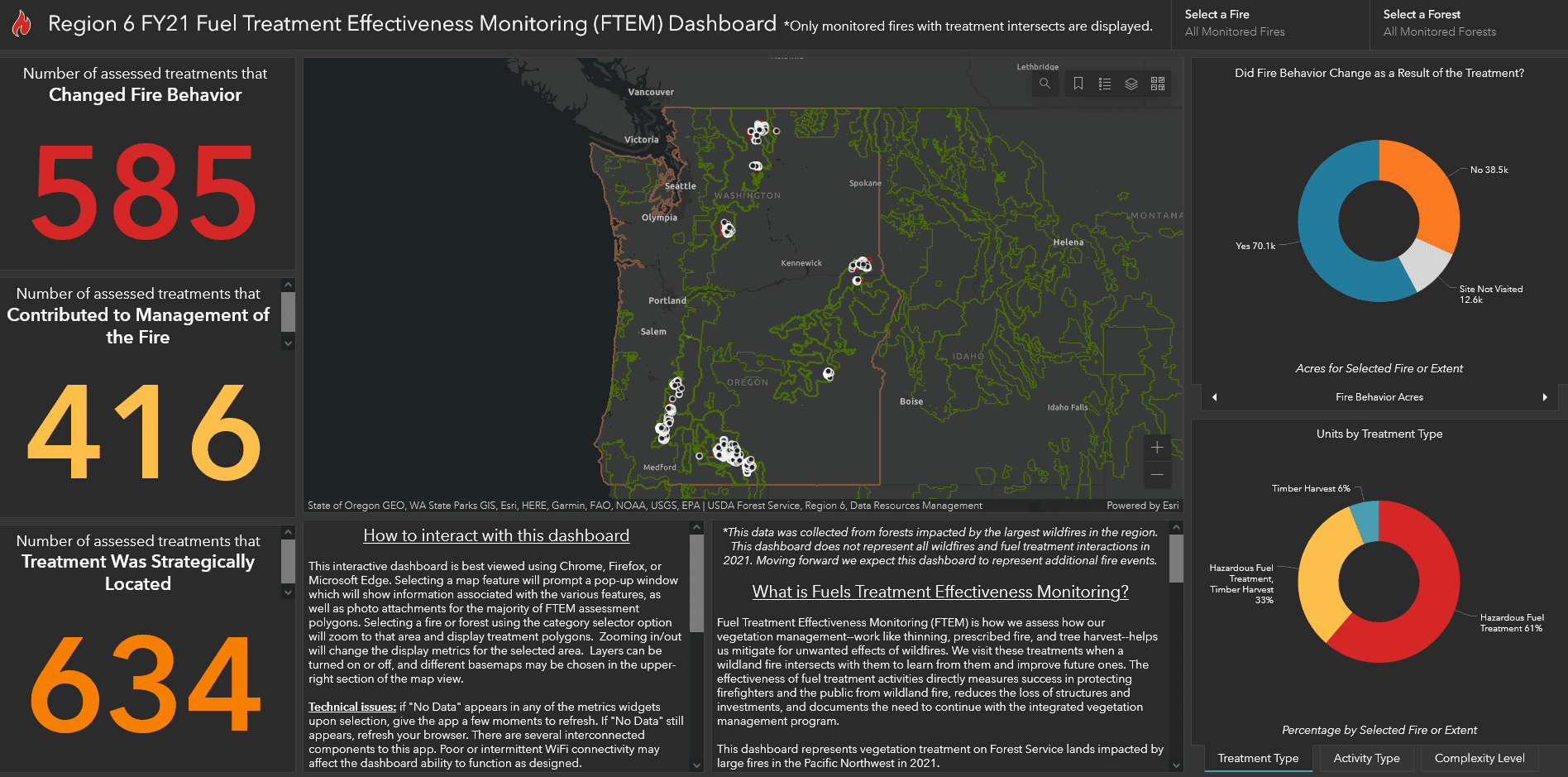

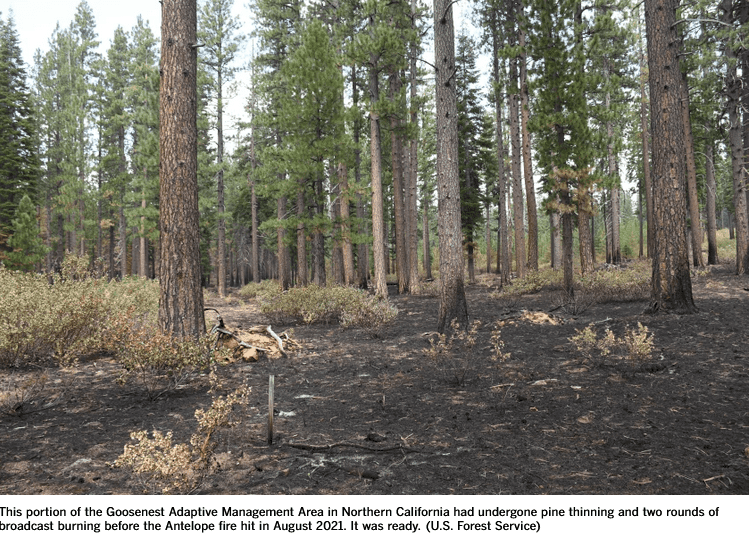

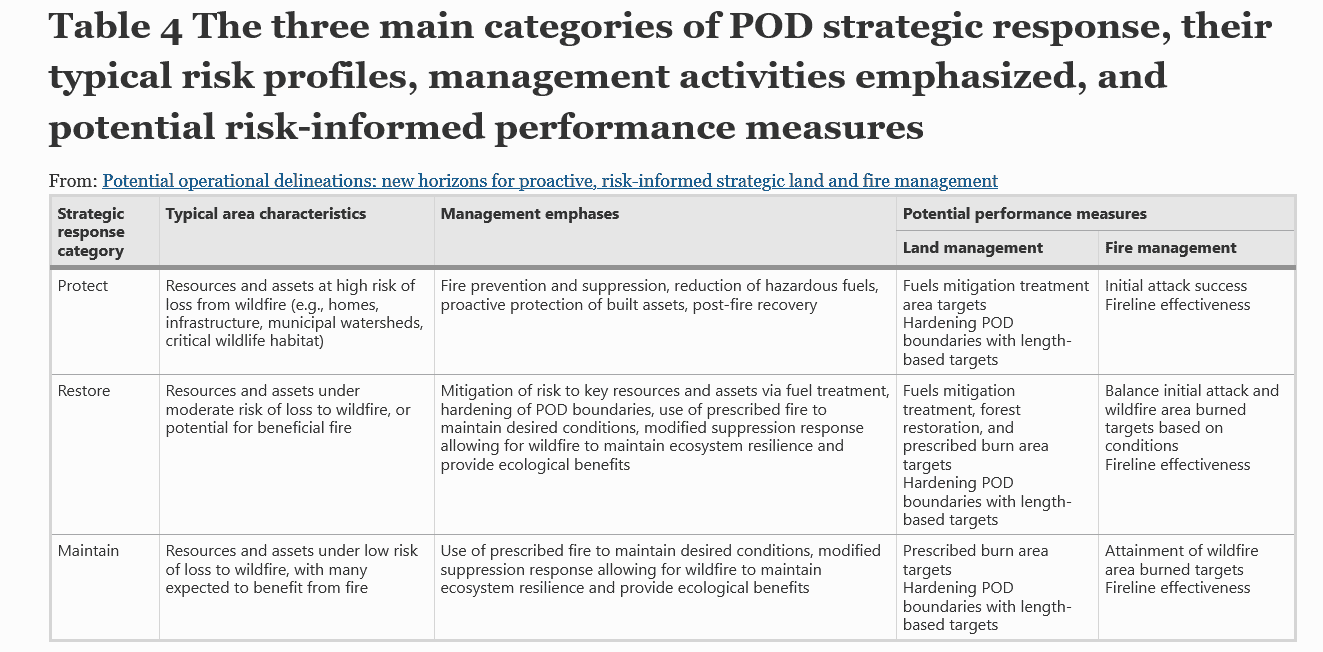

Through a combination of conceptual strategic frameworks and real-world examples, we have demonstrated the potential value of PODs to support wildfire preparedness and response as well as fuels mitigation and forest restoration. A key argument here is that PODs can provide rich opportunities for innovation in both backward-looking evaluative and forward-looking anticipatory frameworks, by leveraging place-based collaboration, science-driven analytics, and risk management principles. We argue that PODs help us prepare for the future by facilitating more informed and adaptive wildfire management strategies and help us learn from the past by providing a logical platform for nuanced performance measurement clearly linked to locally defined fire management objectives. Key aspects of the PODs concept include (1) instilling boundary spanning and anticipatory lenses into wildfire planning efforts; (2) stressing monitoring, learning, and improvement of best practices; (3) co-producing knowledge and infusing analytics with expert knowledge; and (4) delineating fire management and analysis units in ways that are relevant to fire containment operations by linking features like roads, water bodies, and fuel type transitions.

Three salient areas of opportunity for PODs highlighted in this paper are supporting climate-smart forest and fire management and planning, informing more agile and adaptive allocation of suppression resources, and enabling risk-informed performance measurement. These efforts can be synergistic, as the presence of robust plans and decision support can for example support timely identification and communication of incident resource capacity needs, which in turn can support effective response, which in turn will be captured in next-generation performance measures. Similarly, effective assessment and planning based on risks and control opportunity can inform development of fuel break networks and strategic containment units that facilitate both intentional restoration of beneficial wildland fire as well as containment efforts to slow the spread of undesired fire. In sum, enhanced performance of the wildland fire system is premised in large part on enhancements in planning capacity and capability at local levels, and we believe PODs can play an important role in this space.

PODs are by no means a panacea and real challenges remain. The pace and scale of environmental, social, and organizational change is leading to ever more extreme wildfire behavior and consequences. Within this environment, we will likely continue to experience increased negative outcomes even where planned mitigation efforts and response strategies are well organized and based on the best available science. The PODs planning framework is no exception. We outline some potential pitfalls, broken down by thematic area with a description of potential failure modes (Table 7). Some of the themes relate to social aspects of the collaborative process planning process, and lessons learned from previous studies have found that a dedicated and coordinated effort is essential (Greiner et al. 2020; Caggiano 2019) and recommend following the best principles for collaborative engagement and stakeholder involvement to ensure PODs are designed effectively (Talley et al. 2016). Other themes relate to the dynamic nature of the problem and highlight how outdated assessments, plans, and mental models can diminish the value of PODs. The current wildfire crisis will likely result in substantial change to our wildfire management approach including the need to engage new partners, take advantage of emerging technologies, and explore critical resource needs.