A California Conservation Corps crew works on mitigating small diameter trees and branches off Spring Creek Road atop the Ridge in the Sherwood Corridor to help provide a safe exit to Highway 101 in case Sherwood Road is impassible on Feb. 6, 2022.Mathew Caine/Willits Weekly

A California Conservation Corps crew works on mitigating small diameter trees and branches off Spring Creek Road atop the Ridge in the Sherwood Corridor to help provide a safe exit to Highway 101 in case Sherwood Road is impassible on Feb. 6, 2022.Mathew Caine/Willits WeeklyThanks to one of my fave reporters, Sammy Roth of the LA Times, for retweeting this story by Scott Rodd of Capital Public Radio. California seems to be at the forefront of so much in terms of wildfire and climate change, and is such a gigantic force, it’s always interesting to see what they’re up to. I’d be particularly interested in any experiences TSW readers have had with this process. Note the link with our week’s theme of acronyms.

Some excerpts below, but the whole thing is worth reading.

Area residents, who had to evacuate before, are worried about the slow progress.

“It makes me very angry, very cynical, [and] frustrated,” said Brooktrails retiree Luis Celaya, 85. “This is something that is so important and the potential is so high that a fire could happen.”

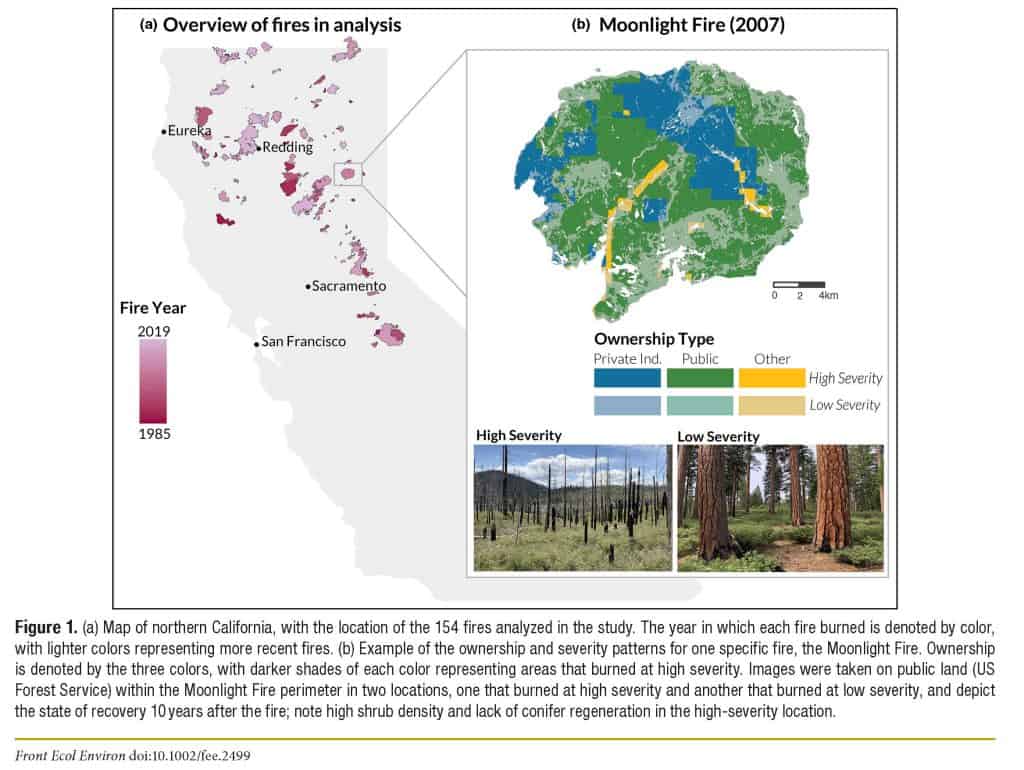

A monthslong investigation by CapRadio and The California Newsroom found that projects across the state, like the one in Brooktrails, are encountering a bureaucratic bottleneck before shovels can even break ground. The state’s byzantine environmental approval process, required under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), is slowing projects from Mendocino County to the Sierra Nevada to the Central Coast. The landmark environmental law was intended to protect ecologically and environmentally sensitive landscapes. But foresters worry that the glacial pace of environmental approvals under CEQA may lead to a much worse outcome — extreme wildfires obliterating these areas.

To combat this, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration launched a program more than two years ago that promised to break the logjam, by fast-tracking environmental reviews. But that program, called the California Vegetation Treatment Program (CalVTP), hasn’t led to the completion of a single project so far. This stands in stark contrast to projections by the state Board of Forestry and Fire Protection, which anticipated CalVTP would lead to 45,000 acres of completed work in its first year.

Keith Rutledge, project manager for Sherwood Firewise Communities in Brooktrails, told CapRadio and The California Newsroom that he had never heard of CalVTP. The nonprofit instead used the established system to satisfy CEQA to clear the first few miles of road, which took over a year. When they later asked a Cal Fire representative about using CalVTP on the rest of the project, the representative discouraged them from using the new program, cautioning it would be even more burdensome, according to multiple sources familiar with the matter.

In interviews, foresters and fire prevention experts around the state said they still don’t fully understand how the program is supposed to work. Others were turned off by the large amount of unfamiliar paperwork required under the program. CalVTP’s official workflow template, published on the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection’s website, includes a dizzying decision tree of acronyms.

Fire prevention project managers who’ve tried to use the program have faced unforeseen hurdles. For example, the Central Coast Prescribed Burn Association wanted to use a single CalVTP application for a series of controlled burns across Santa Cruz, San Benito and Monterey counties. The 10 prescribed burn sites would help protect homes and ecologically sensitive habitats, including freshwater wetlands. The threat of fire isn’t hypothetical in this area — just two years ago, the 48,000-acre River Fire burned within 15 miles of one project site.

But the projects straddle two Cal Fire units, according to Nadia Hamey, a forester and environmental consultant working with the burn association. She said each unit wanted a separate CalVTP application for the proposed burns in their area. Completing two versions of the new, unfamiliar paperwork proved too burdensome.

So the burn association decided to use the traditional environmental review process. That required 10 separate project applications. As of this winter, two burns had been completed, with the rest moving through the development and approval process.

………………

And of course, litigation-induced uncertainty..

Although two years had passed since Newsom formally launched the program, Kerstein told lawmakers that “it’s very early days” for CalVTP.

There are other potential complications. A lawsuit brought by two groups opposed to CalVTP’s expedited environmental review — the California Chaparral Institute and the Endangered Habitats League — could invalidate CalVTP completely or introduce more burdensome and timely hoops for forest managers to jump through, according to a memo from the Board of Forestry.

While the lawsuit isn’t preventing any projects from moving forward right now, the board memo cautions that project managers should consider the “uncertainty” posed by the litigation before using CalVTP.

***************

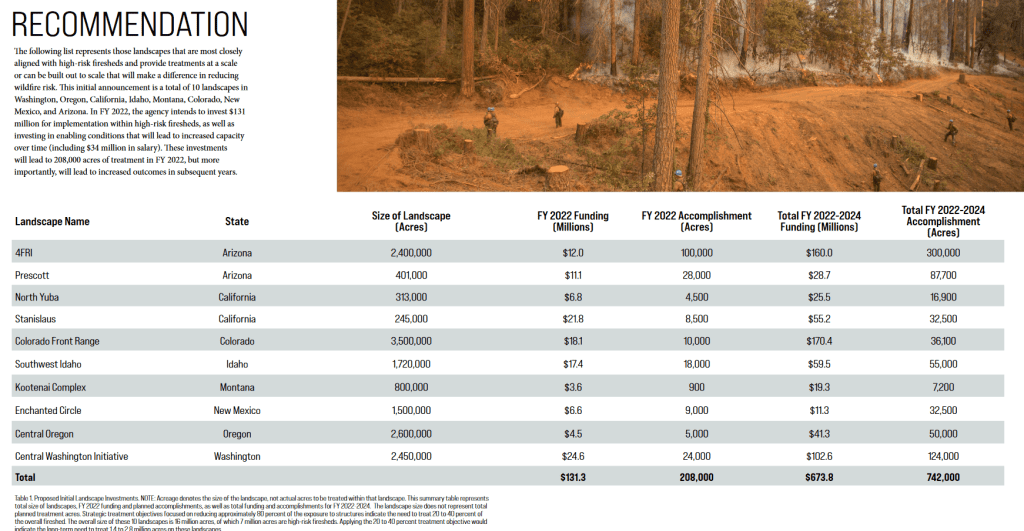

The agency did not provide current figures on the number of project acres approved through CalVTP. In December, it told CapRadio and The California Newsroom that the program had approved 28,000 acres.

“This is not enough by any stretch of the imagination,” said Char Miller, professor of environmental analysis and history at Pomona College, who has monitored the development of CalVTP. He says California has millions of acres in desperate need of forest management and fuel reduction.

**********************

I think we mostly agree with Miller’s observation.

TSW readers may remember that Miller also wrote in 2018 in an op-ed with Chad Hanson in the LA Times and other outlets.

The science is clear that the most effective way to protect homes from wildfire is to make homes themselves more fire-safe, using fire-resistant roofing and siding, installing ember-proof vents and exterior sprinklers, and maintaining “defensible space” within 60 to 100 feet of individual homes by reducing grasses, shrubs and small trees immediately adjacent to houses. Vegetation management beyond 100 feet from homes provides no additional protection. Subsidizing logging in remote forests won’t protect us; we need to live with fire, the way we do with earthquakes.

Here’s Matthew’s TSW post about that op-ed and associated comments.

*********************

Anyway, if you were the State, what would you do to fix this?