I’ve been interested in how stories get covered by various journalists and press entities. In 2019, I attended a session for journalists learning about wildfires at the Society of Environmental Journalists conference in Fort Collins. There were many fascinating differences between their culture and that of, say, SAF, including high quality free food, drink, and swag from ENGOs.

I think it’s worth listening to the recording, of the session to get an idea of how others think and talk about what’s important about wildfires. Some seem absolutely sure of things that we all know are contested among both scientists and practitioners. But maybe it’s just a cultural way of making statements and sounding sure.

It’s especially interesting to listen to these 2019 ideas with our current knowledge of how Congress, California, and Colorado are currently putting megabucks into fuel treatments.

At the beginning, the moderator, Michael Kodas, introduces the speakers and says that George Wuerthner’s book is an “excellent resource for covering wildfire issues.”

****************

Here’s a quote from a recent op-ed of Wuerthner’s from July 2021:

Today, with regards to wildfire, we should be saying over and over, it’s the climate stupid! The heat, drought and other variables caused by human climate warming is super-charging wildfires. Yet the response of most agencies and politicians is to suggest more logging/thinning as a panacea.

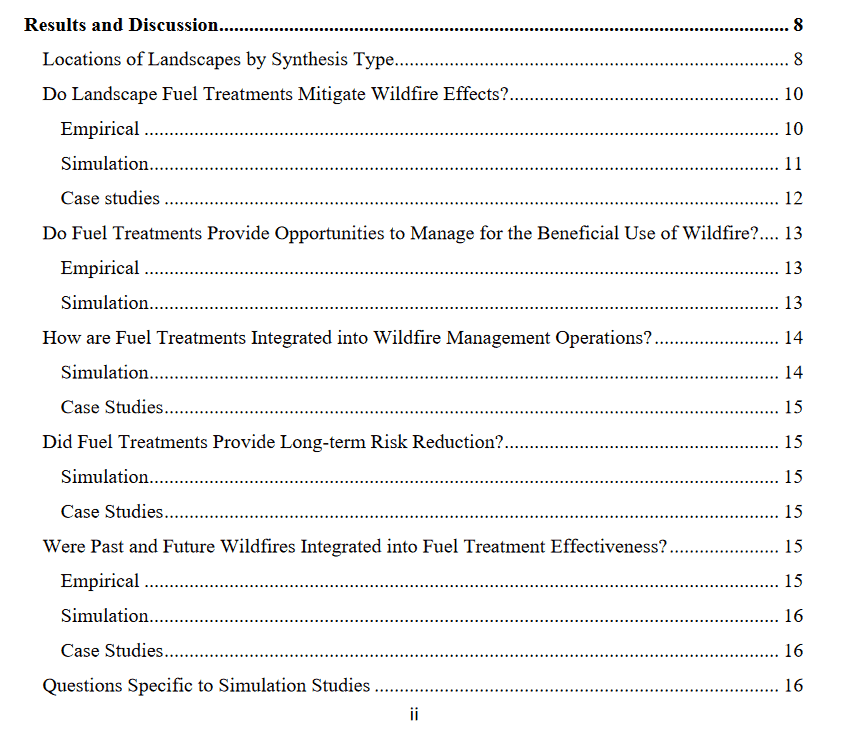

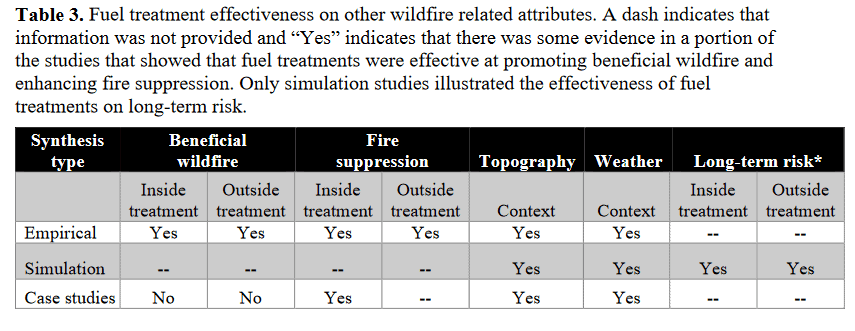

The proponents of active forest management assert that these tactics can reduce fire intensity and thus is a beneficial policy to reduce large blazes. However, fuel reductions do not change the climate or weather. And most of the scientific support for thinning/logging is based on modeling of fuel loading, not real-life experiences.

By promoting “active forest management” as a panacea for wildfire, we trade inevitable negative consequences of logging/thinning that occur today and get only a tiny chance that any fuel reduction will influence a wildfire.

There are so many interesting things about these statements.

“most of the scientific support for thinning/logging is based on modeling of fuel loading, not real-life experience”

This is probably one of the reasons the group of scientists wrote the 10 Common Questions paper.

“get only a tiny chance that any fuel reduction will influence a wildfire.”

But we’ve seem FTEM numbers that don’t agree with that (plus our own experiences).

Do any of us think that if we stopped producing GHGs today our fire problems would go away?

Marc Heller of E&E News also quoted Wuerther last month in the article mentioned here:

A debate over the practice continues to play out.

One of the skeptics is George Wuerthner, a Bend, Ore., ecologist and director of Public Lands Media, part of the environmental group Earth Island Institute. Wuerthner told E&E News he’s not convinced of the main argument behind prescribed burning — that decades of total fire suppression have led to overstocked forests that need to be cleared in part with fire.

Wuerthner said that in his view, increased wildfires aren’t being driven so much by too much fuel as by climate change.

“Fuels are not what is driving large blazes,” Wuerthner said in an email. “Climate/weather that includes low humidity, drought, high temps, and most importantly wind. And prescribed burning does nothing to change those major influences.”

And prescribed burning and other fuels-reduction work doesn’t necessarily diminish wildfires when they do come, Wuerthner said, although the Forest Service pointed to several examples from 2021 suggesting the opposite.

Wuerthner pointed to the Camp Fire that destroyed thousands of homes in Paradise, Calif., in 2018. In that case, he said, the fire burned through areas that had been treated through logging and prescribed burns, thanks to high winds.

So Wuerthner is actually against prescribed burning, as well as the less popular thinning. Which I think makes him an outlier, although an apparently popular one. When are outliers worth reporting on and when are they purveyors of “misinformation”? (Rhetorical question)

****************

A couple of other observations:

Rod Moraga was the only fire suppression person presenting.. it makes me wonder why more current IC folks aren’t out and about telling their stories. are they not available, or don’t moderators ask? Or don’t they know whom to ask? Is there a communications plan for the Interagency Fire folks? Or each agency’s fire folks? It seems like that would be increasingly important as social license is developed for prescribed and MFRB fires.

One of the speakers, Chela Garcia of the Hispanic Access Fund, at about 18:46 talks about an experiment the Forest Service is doing working with the acequia system to pay a mayordomo and leñeros to thin 275 acres. They have a year’s time to finish the blocks and are paid $300 on completion according to this interesting article on the Kiowa-San Cristobal WUI (Carson NF).

There’s a lot there, so please share your observations. It looks like you can listen to any of the other presentations as well (climate, Indian Country, solutions journalism and so on.

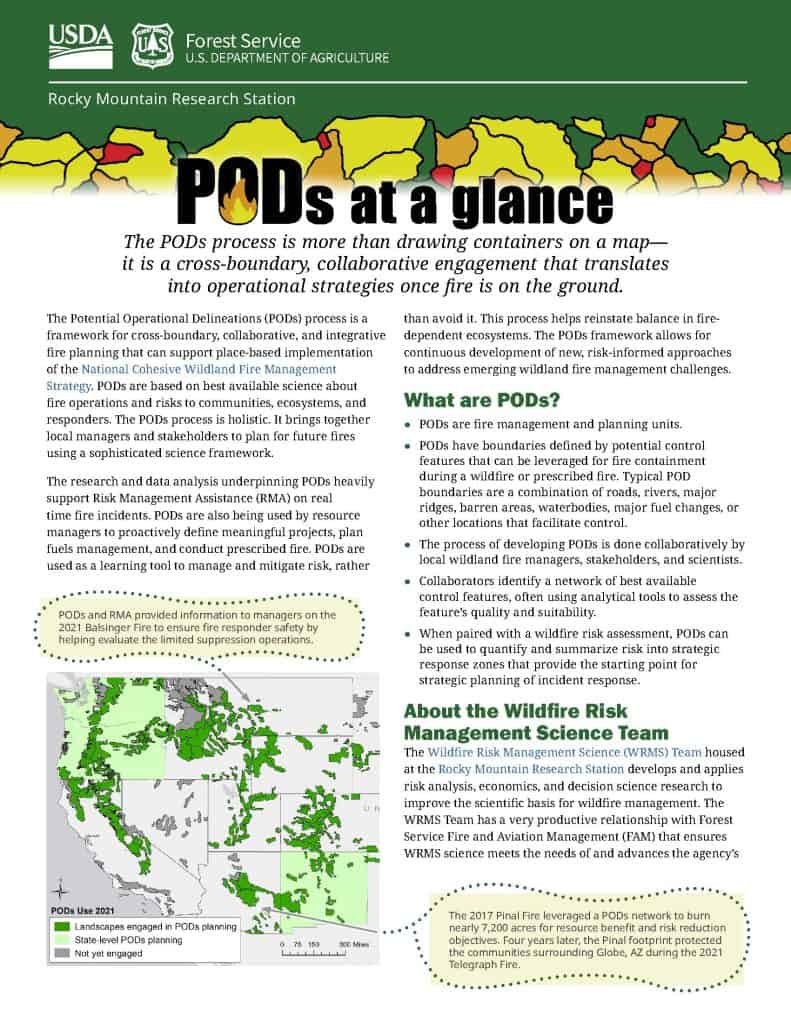

We had also been talking about why more panels and media don’t involve fire suppression folks.. here is a video from RMRS that does just that.. about PODS.

We had also been talking about why more panels and media don’t involve fire suppression folks.. here is a video from RMRS that does just that.. about PODS.