I am reposting this because I think it’s important and perhaps people missed it because Steve also posted yesterday. The question for readers who are currently working or involved in collaborative groups is “do you think some of these ideas are worth considering in your part of the country?”

There are many news stories about projects in litigation, or where there are controversies. Forest Service folks may remember the management training of “catching people doing something right.” The SERAL (Social and Ecological Resilience Across the Landscape) efforts are successful at getting large-landscape treatments done. Are there ways that other Forests and communities can learn from these efforts?

This story deserves much greater play in larger media IMHO. I’m thinking a NY Times, WaPo, or NPR-style set of emotion-inducing interviews, drone overflights, and all that. I’ll be sending this to journalists with that wish. It would also be an interesting case study for social scientists interested in trust building and collaboration.

From this January

“SONORA, Calif. (January 11, 2024) – In an incredible show of faith and recognition for work already accomplished, the Stanislaus National Forest recently received its annual budget for work on the Stanislaus Wildfire Crisis Strategy Landscape of $57.6 million.

“This funding level is a clear indicator that we are on the right path with our work and should continue at full speed,” said Stanislaus National Forest Supervisor, Jason Kuiken. “Not only is that apparent as people drive up Highway 108 and see with their own eyes the work, but it’s an acknowledgement all the way from Washington, D.C. that this work should continue.”

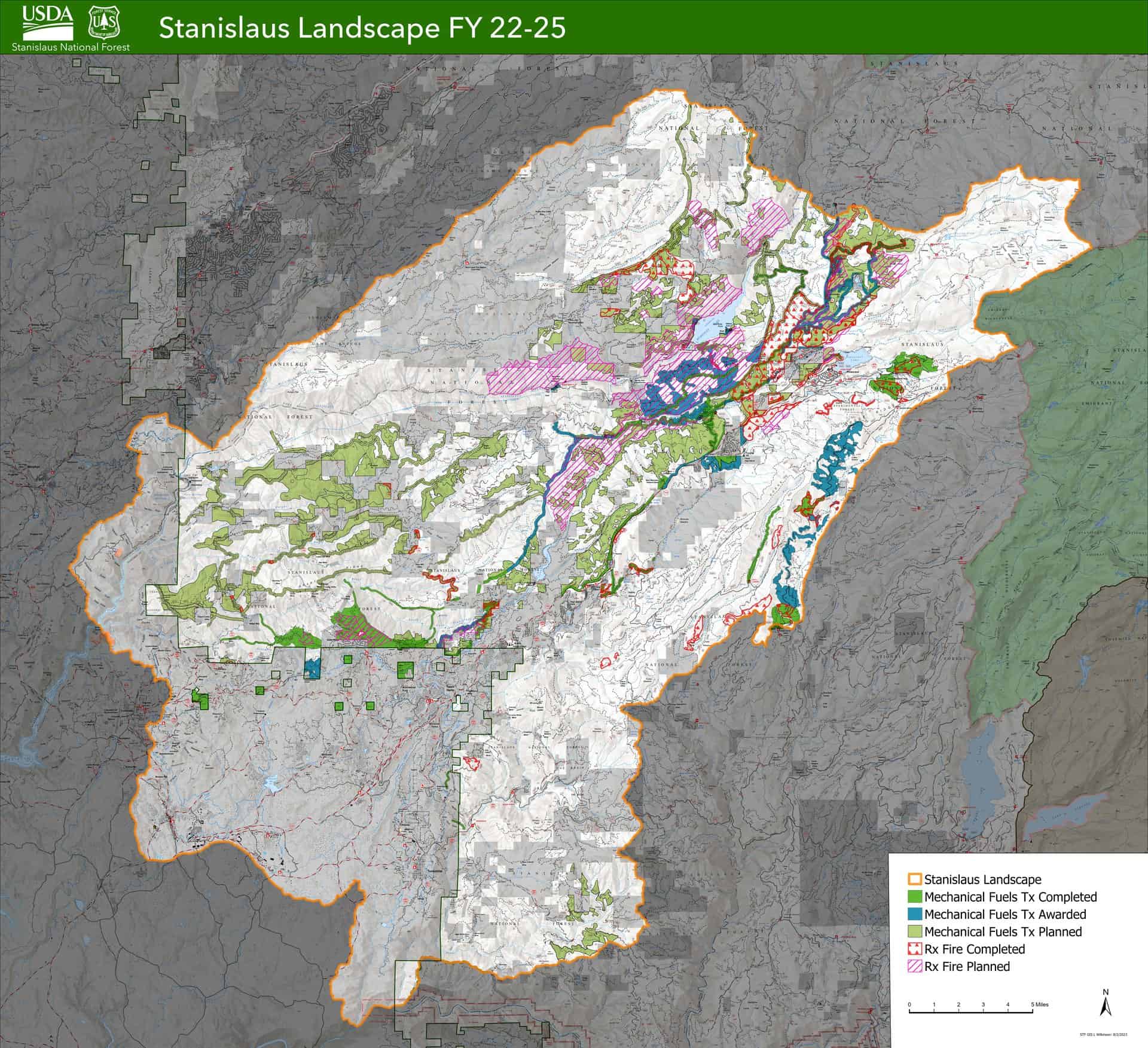

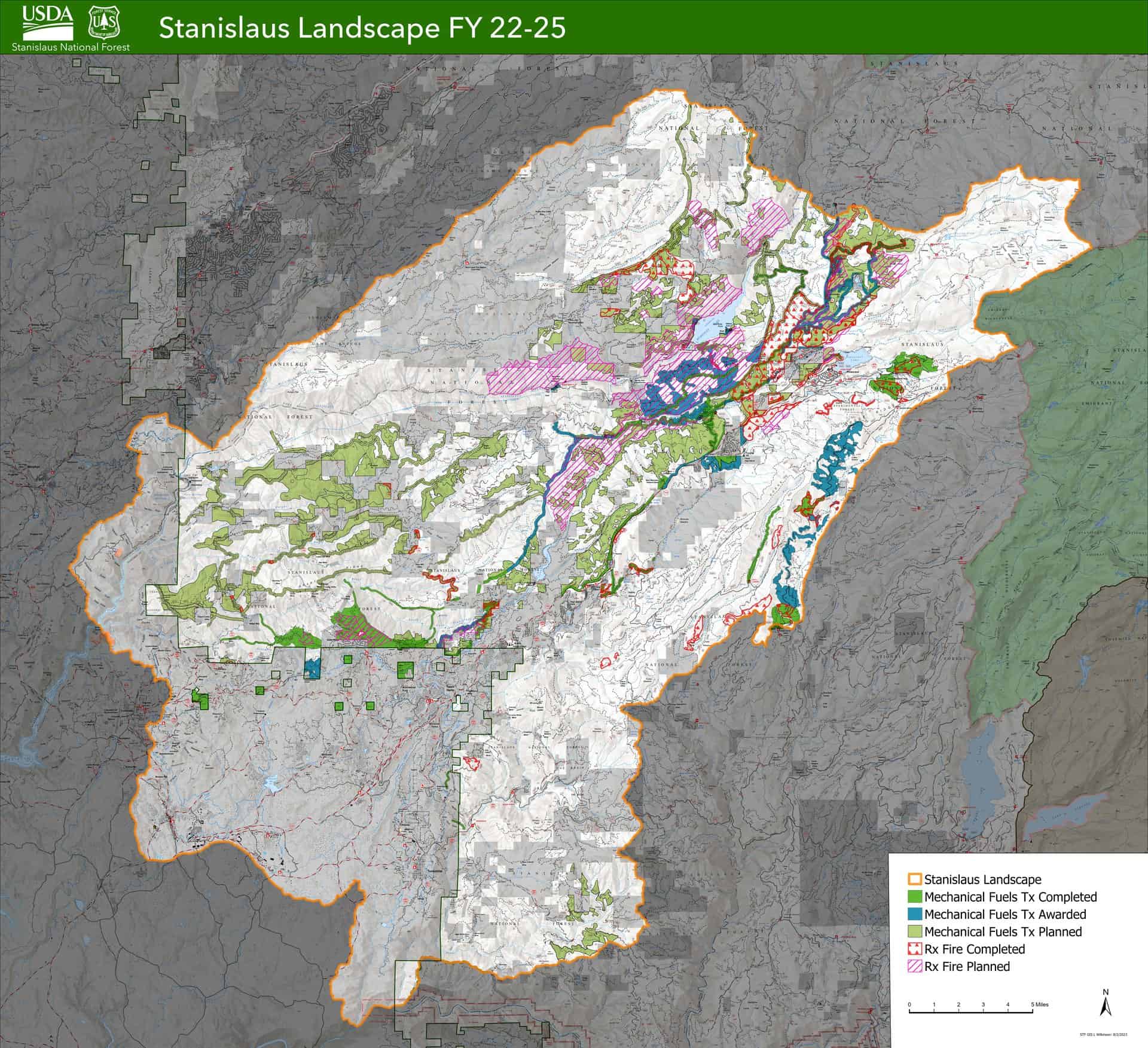

Part of the Forest Services’ Wildfire Crisis Strategy, the Stanislaus National Forest is currently into year three of a ten-year, 305,000 acres project to reduce fuel loads on the forest through a variety of methods to include mechanical thinning and the application of prescribed fire.”

********************

First of all, the Forest has an very helpful website on this project, well worth checking out. It includes a story map that tells the story with photos and videos.

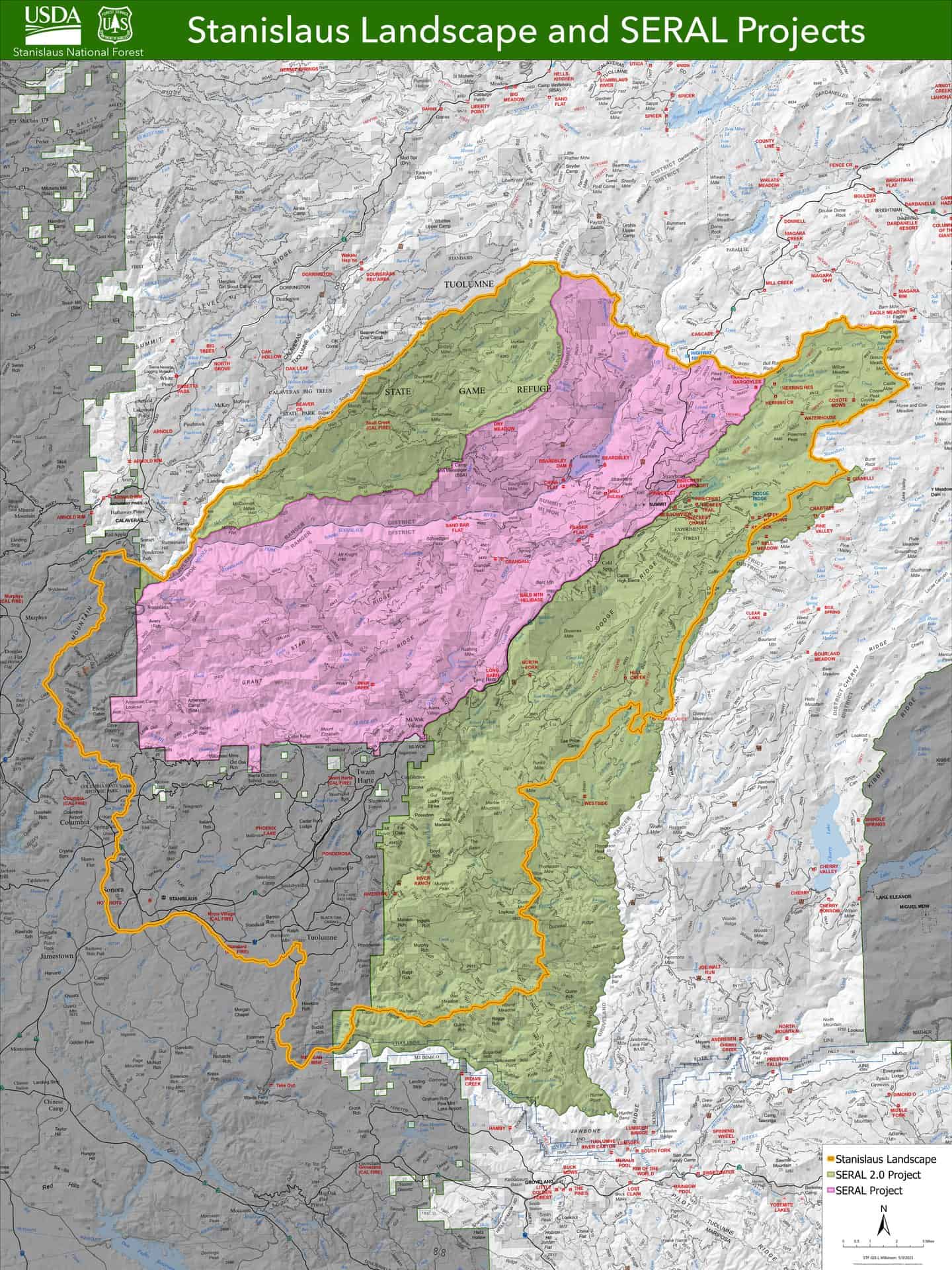

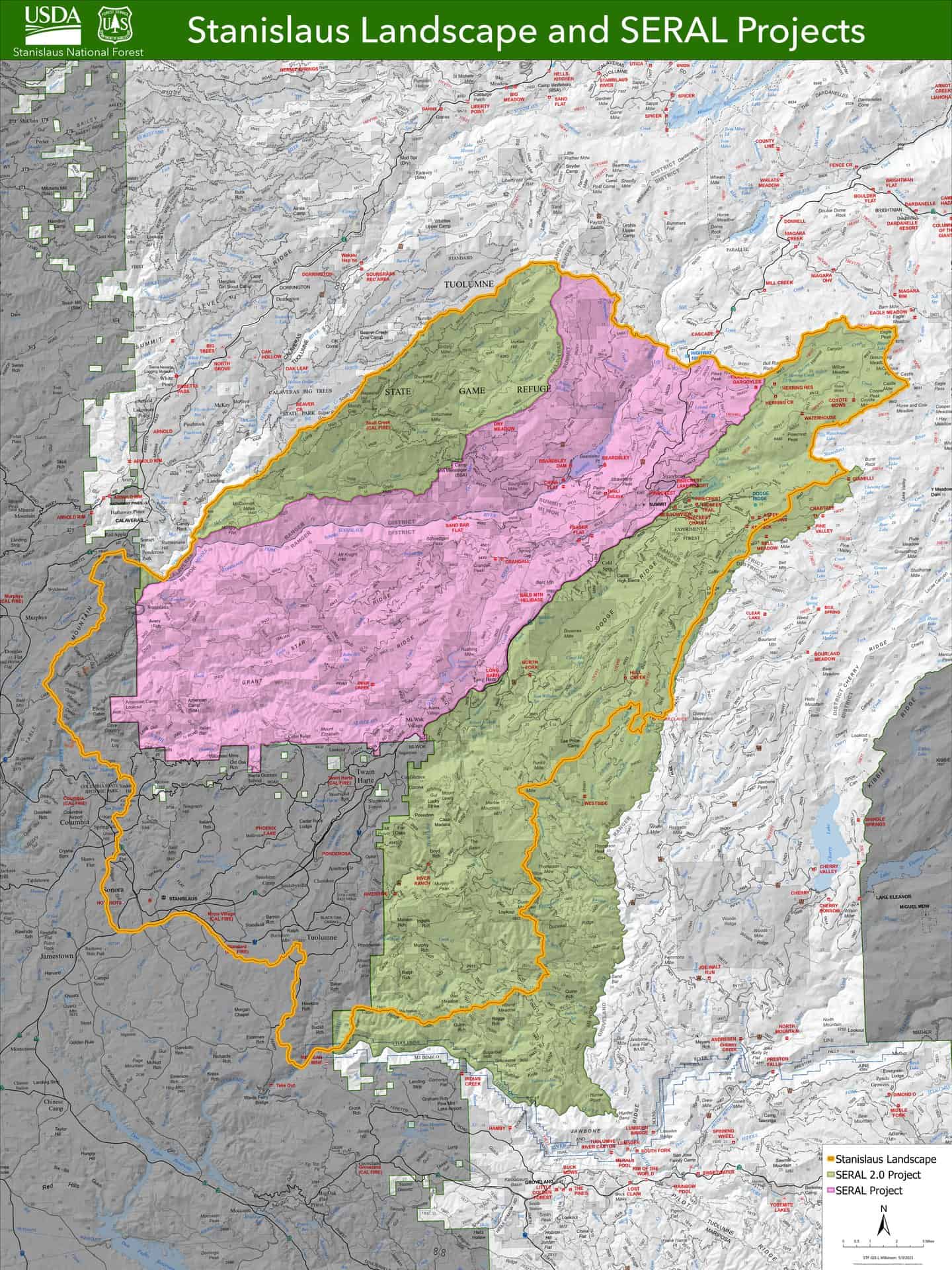

Background: The first decision is Seral 1.0, which called for work on 55,000 acres; currently the Forest is taking public comment on Seral 2.0, which covers another 100,000 acres. The area is part of the one of the priority landscapes for the Wildfire Crisis Strategy (think $). The priority landscape itself encompasses more than 300K acres and the non-SERAL parts include Wilderness and other decisions and collaboratives (see map above).

So let’s look at some of the ways that this success became possible.

1. Yosemite Stanislaus Solutions Collaborative Group

In an interview, the first thing that Supervisor Kuiken pointed to was the efforts of a collaborative group called Yosemite Stanislaus Solutions. You can learn about them here on their website. It includes everyone from Audubon and the Sierra Club (local chapters) to Sierra Pacific, Dirt Riders, Tribal folks and so on. You can check the partners out here.

From the YSS webpage:

“After decades of adversarial “wrangling” over forest management policy, 25 local industry, environmental, and recreational groups decided it was time to focus on what we could agree on,” said Mike Albrecht, president, Associated California Loggers.

“When we sat down together, we found out we agreed on a lot, and so Yosemite Stanislaus Solutions (YSS) was born. YSS agreed to salvage logs the Rim Fire, get it reforested, develop a fuel break network to protect our local communities, and restore meadows, streams, and wetlands to better health,” Albrecht said. “This agreement has gotten us national attention and subsequent funding to undertake large “landscape level” forest management projects. This would not have been accomplished without the close 3-way partnership between Tuolumne County, YSS, and the U.S. Forest Service. Kudos to everyone that has worked so hard to make this happen!”

2. The Rim Fire Galvanized the Community

The Rim Fire burned 402 square miles (260K-ish acres) with a “wide range of intensity and impacts.” These photos show that, at least in some areas, much restoration work for watershed, and to restore tree cover will be needed. The experience of this fire showed the need for work at the landscape scale. It was the third largest wildfire in the State at the time.

“John Buckley, executive director of the Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center in Twain Harte, is also active with Yosemite Stanislaus Solutions. An immediate lesson learned was that doing scattered piecemeal fuel reduction projects, timber sales, mastication of brush, and isolated prescribed burns simply wasn’t going to be enough to prevent more Rim Fire type catastrophes. “That led the YSS forest stakeholder group to come together stronger than ever before to work to get tens of millions of dollars in grants to supplement the work that the Forest Service was already planning to accomplish,” Buckley said.”

3. At First Collaborators Worked Together on Reforestation

Perhaps getting to the “topics with more disagreement” was helped by relationships forged during the work on “topics with agreement.” Also, jointly doing work instead of just talking about how the FS should do it, perhaps caused a greater sympathy for difficulties and trust in Forest Service actions.

4. Getting Work Done Through Partners

Various master agreements, including with the County, enabled finances to be transferred and work to be done without federal hiring or FARs difficulties. Counties and others can hire locally, so that issues like housing affordability may be less pressing.

5. Consistency of Forest Service Personnel and Alignment

Partners are always asking for this. While personnel have indeed changed, the commitment to the process has not. There have been three Forest Supervisors involved during and since the Rim Fire. How did the Forest Service pull this off? Personalities, policy or processes or all of the above?

6. They Were Able to Work Together on Traditionally Tougher Issues.

Example: fire salvage. As TSW readers know, salvage can be controversial, even in the Sierra Nevada.

“Because all the YSS stakeholder interests supported the compromise salvage logging plan, it managed to gain Forest Service approval and got implemented without any legal delays that would have meant a lot of the wood could have rotted,” Buckley said. “By working for consensus middle ground on the issue of salvage logging and then the following debate over how to do national forest reforestation, YSS set a national example — showing the benefits of diverse stakeholders working together in a spirit of compromise and cooperation.”

7. Role of Models and Scientists

Because this work was at the landscape scale, it required thinking beyond the stand level, including the development of PODs. This includes practitioner knowledge, and newer technologies (e.g., Lidar) and models were used; including workshops for the collaborative group with scientists. Supervisor Kuiken would advise anyone “these new technologies and models can be very helpful and save a great deal of time.”

Probably a heavy direct involvement by scientists also helps collaborators learn together and operate from the same knowledge base.

8. NEPA Opportunities and Choices.

They did an EIS for Seral 1 and will do one for Seral 2. You can read the notice of intent on the Federal Register here. I get the feeling that the way that the decisions are structured such that analyzed activities may occur over time with no new decisions required. So big EIS, but considers many kinds of treatments over a large area over a long time period. For example, ongoing maintenance of fuelbreaks is included in the decision. If stands die due to bark beetle, that is also incorporated.

They are using some emergency authorities, specifically “only the proposed action and a no-action alternative” and “no pre-decisional administrative review process.” In the case of Seral 2.0, potentially more controversial decisions will be covered in separate RODs based off the EIS.

They have used new technologies, like Lidar, to help with the analysis.

Inquiring NEPA minds might want to know “does this decision incorporate “condition-based management””?

Katie Wilkinson, the Forest Environmental Coordinator, addressed this in an email.

“The SERAL projects only have aspects of condition-based management – salvage, rapid response to newly discovered non-native weed infestations, hazard tree mitigation (only in SERAL 1.0).

The large majority of the SERAL projects proposed or authorized actions however, would not be considered condition-based management. The SERAL decisions authorized site-specific vegetation management actions (other than those listed above) and the SERAL 2.0 decision will do the same. Modifications do occur from planned units to implementation units, regularly, based on a variety of factors or updated survey information considered and obtained internally.

None of the SERAL implementation will go through additional public review or comment periods. The SERAL analysis document includes the site-specificity necessary to provide meaningful feedback and public comments and for the decision maker to make an informed decision. That doesn’t diminish the amount of work left for the implementation team to complete after the decision and prior to implementation. “

9. Lack of Litigation. We’ve all seen collaborative groups work together well, with the decision then followed by litigation. This was not the case for Seral 1.0. We can’t FOIA internal documents of potential litigants to understand why they did not file. Certainly litigation does occur with similar kinds of projects in the Sierra Nevada. When asked why Supervisor Kuiken replied in an email: collaboration on developing the proposed action (and associated response to the public concerns) and second that the IDT made a DEIS/FEIS that was both thorough and readable/understandable.

I’m thinking that it may also have something to do with the choices made by potential litigators, and the political horsepower behind the project. Certainly a previous effort (salvage) was litigated, as we covered earlier on TSW. I’ll try to find out more about this.

Summary

The SERAL efforts have been successful.Let’s look more deeply and share this information.

TSW readers: what aspects of this effort do you think are replicable where you work? Why or why not? Ideas for reporters to send this to.. either in comments or contact me directly.

Reporters: What might be interesting angles..

*What makes people who usually disagree come together? Interview various members of YSS. Link to election year and reducing polarization? Something like this NY Times story about Blue Mountain Forest Partners.

*When Litigants Stay Home and Why: Interview folks who litigated on the Rim Fire and not on SERAL 1.0, and ask them about their rationale.

*Climate change and carbon:given the many op-eds that simply claim “leaving mature and old growth trees alone is best for carbon” how does the Forest and YSS think about carbon. Interview some scientists involved (and those who disagree).

*Old -growth.. how will old growth be delineated and protected in Seral 2.0?

*Digging into how they used new technologies in their work, and new ideas like PODs.

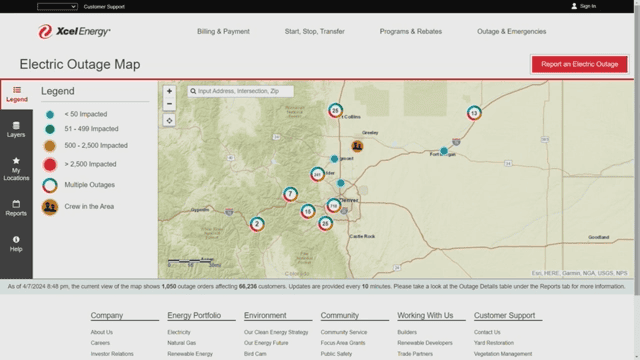

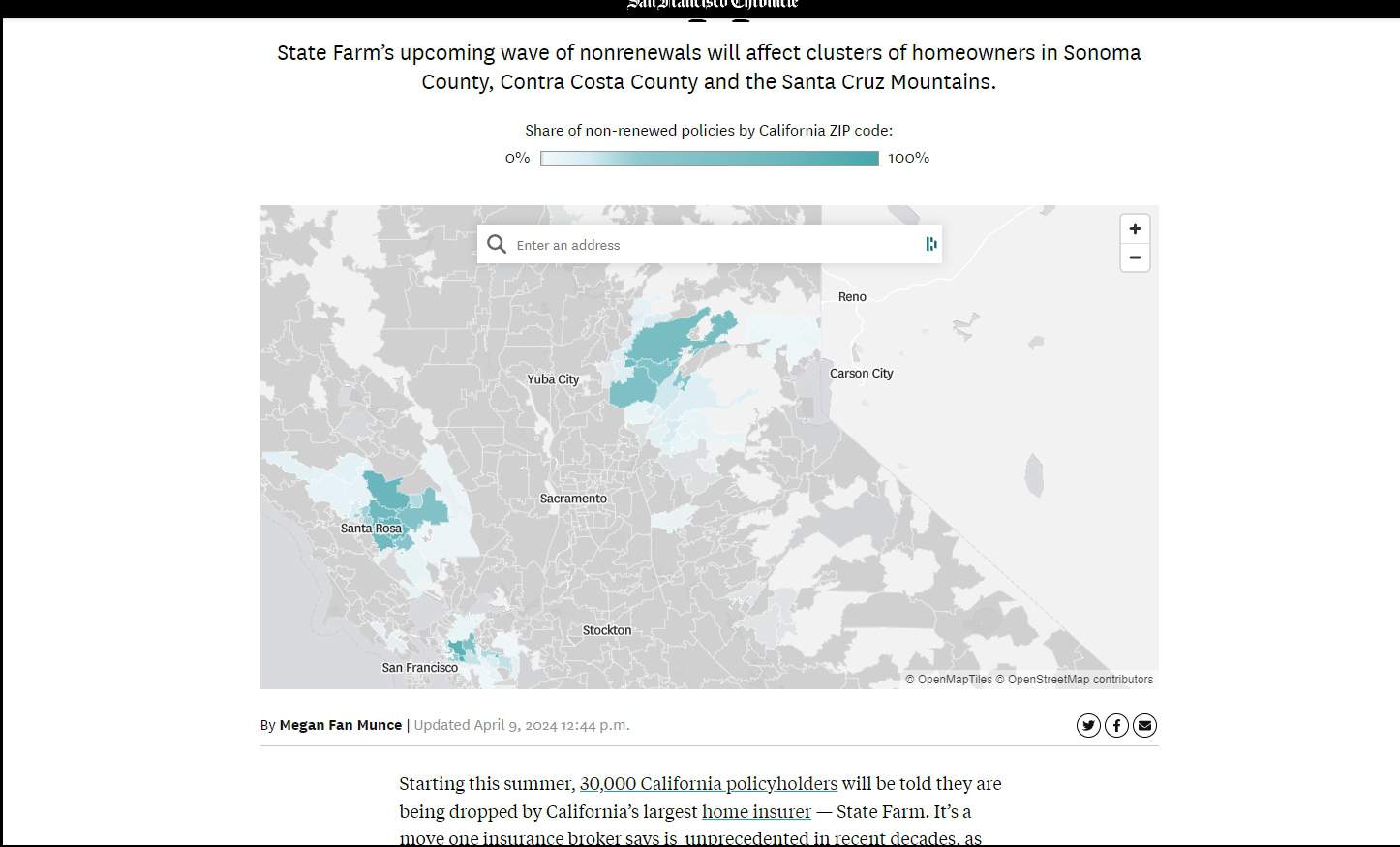

Pretty sure this isn’t about wildfire risk based on this map.

Pretty sure this isn’t about wildfire risk based on this map.