Many thanks to Matthew for posting the Downing et al. paper from Nature. There are so many fascinating things about this paper, I thought it was worthy of looking at carefully. 1) what the paper says (results) 2) how those relate to the methods (logic paths) and 3) how the conclusions made their way from the paper to the OSU public affairs and other media reports. It’s a terrific example, because you don’t have to understand the methodologies to understand the knowledge claims and logic. I’m hoping this analysis will be helpful to students and the paper is open source so anyone can view. This is a longer post than usual.

The first step is always to look at results and discussion.

Conclusion

Our empirical assessment of CB fire activity can support the development of strategies designed to foster fire-adapted communities, successful wildfire response, and ecologically resilient landscapes.

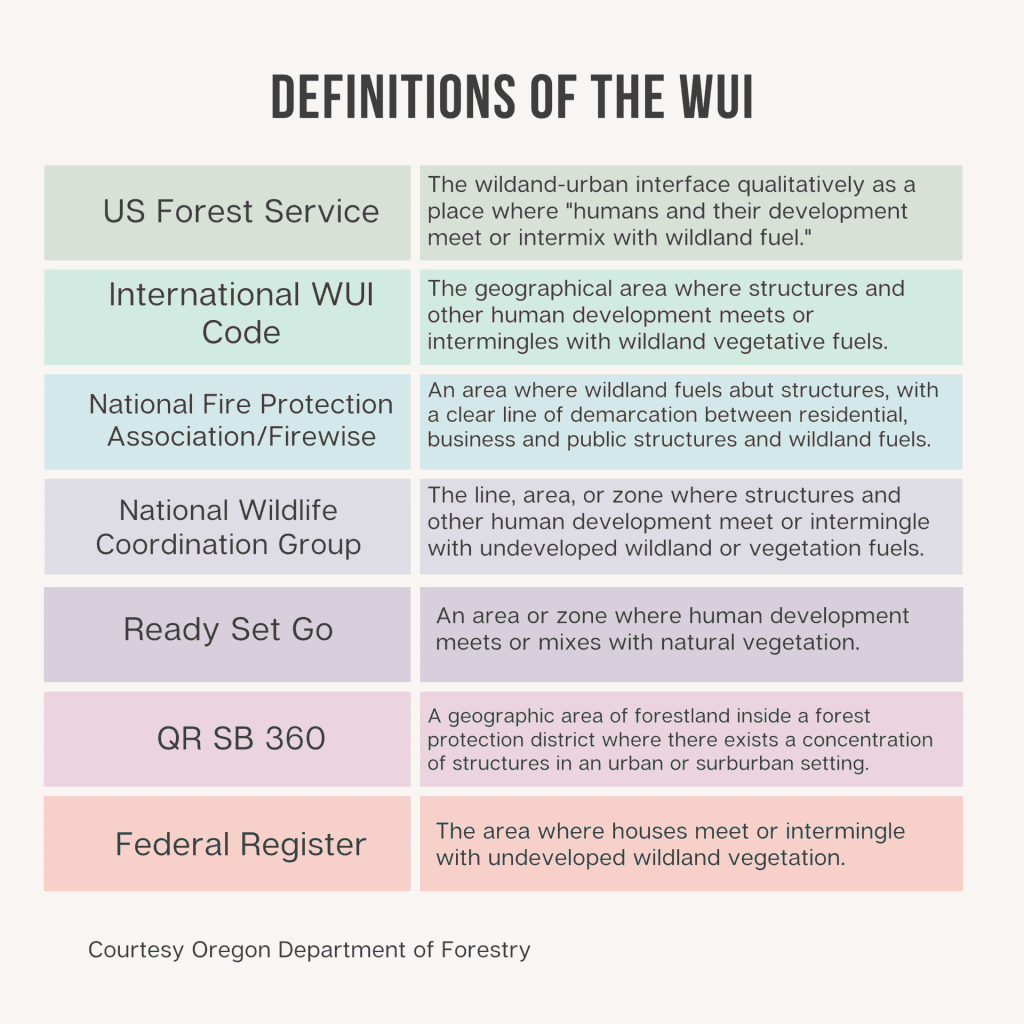

Then try to translate this from academic talk. First, they talk about “cross boundary” wildfire, in fact, the whole paper is about “cross boundary” wildfire, so that is fires that move from private to public land or vice versa. Why is this important? They discuss this in a few paragraphs.

The tension between ecological processes (e.g., fire) and social processes (e.g., WUI development) in mixed ownership landscapes is brought into stark relief when fire ignites on one land tenure and spreads to other ownerships, especially when it results in severe damages to communities on private lands and/or highly valued natural resources on publicly managed wildlands. These cross-boundary (CB) wildfires present particularly acute management challenges because the responsibilities for preventing ignitions, stopping fire spread, and reducing the vulnerability of at-risk, high-value assets are often dispersed among disparate public and private actors with different objectives, values, capacity, and risk tolerances23–25

. Some CB risk mitigation strategies exist, such as fire protection exchanges, which transfer suppression responsibility from one agency (e.g., state) to another (e.g., U.S. Forest Service), and CB fuel treatment agreements, which allow managers to influence components of wildfire risk beyond their jurisdictional boundaries 2,26 . Improving CB wildfire risk management has been identified as a top national priority 27 , but effective, landscape-scale solutions are not readily apparent.

A common narrative used to describe CB fire is as follows: a wildfire ignites on remote public lands (e.g., US Forest Service), spreads to a community, showers homes with embers, and results in structure loss and fatalities 23,25,28 . In this framing, public land management agencies bear the primary responsibility for managing and mitigating CB fire risk, with effort focused on prevention, hazardous fuel reduction, and suppression—largely reinforcing the dominant management paradigm of fire exclusion 29,30 . An alternative risk management framing of this challenge has emerged, starting with the axiom that CB fire transmission is inevitable in fire-prone mixed ownership landscapes and that private landowners and homeowners are the actors best positioned to reduce fire risk to homes and other high-value assets regardless of where the fire starts 31 . In the absence of a broad-scale empirical assessment of CB fire transmission, it is difficult to determine which of these narratives more accurately reflects the nature of the problem, and whether CB fire risk management is best framed in terms of reducing fire transmission from public lands or decreasing the exposure and vulnerability of high-value developed assets on private lands.

So there’s a framing question here. Where I live, people don’t much care where a fire starts, just if it’s burning close to them. So the importance of addressing wildfire with the CB framing is based on a “common narrative” with cites 23, 25, and 28. 28 is an interesting paper by Ager et al., definitely worth taking a look at, about Central Oregon, where they found:

Among the land tenures examined, the area burned by incoming fires averaged 57% of the total burned area. Community exposure from incoming fires ignited on surrounding land tenures accounted for 67% of the total area burned.

I would call that an observation, rather than a narrative, but perhaps I’m being pedantic. For those who don’t track this stuff, Ager’s groups’ transmission and scenario analysis forms the basis for the prioritization scheme in the Forest Service 10 year action plan.

As to “Improving CB wildfire risk management has been identified as a top national priority 27 , but effective, landscape-scale solutions are not readily apparent.” I think this is important as in a brief review of their cite to the Fire Plan Implementation Strategy, I didn’t actually see a reference to “cross boundary”- maybe others can find it. The other thing I’d point out is that PODS look like they might be an effective landscape-scale solution and they seem apparent to me. So outside of a scientific paper, that would be an interesting conversation to have.

I found the conclusions interesting as I have just spent several days working on the logic of “fires are increasingly difficult and unpredictable due to fuel accumulation, climate change and increasing amounts of human infrastructure, therefore we need to keep all the tools in the toolkit, including prescribed fire and the Thing Formerly Known as WFU.” This was rather well-stated IMHO in Wildfire Resolution Letter on TFKWFU:

As we have seen over the past few years, especially in California and Colorado, we are now experiencing conditions that are causing extreme fire behavior, which is in part due to past full suppression policy. The best management approach we have to combat this phenomenon is reducing the amount of fuel available to burn. Similar to how important thinning and prescribed burning are around our communities, the ability to manage wildland fires at appropriate times is equally important for reducing fuels in the wildland environment. We will never be able to reduce fire risk to communities with thinning or prescribed fire alone—we need all hands on deck, and all the tools in the toolbox.

So it looks like the authors of the Downing et al. paper ended up in a different place from many other practitioners and the usual fire science suspects. To me this is a Science Situation That Shouts “Watch Out.”

So that’s why we need to dig deeper.. let’s go to conclusions again in their paper.

Conclusion

Our empirical assessment of CB fire activity can support the development of strategies designed to foster fire-adapted communities, successful wildfire response, and ecologically resilient landscapes. Adapting to increasing CB wildfire in the western US will require viewing socio-ecological risk linkages between CB fire sources and recipients as management assets rather than liabilities. We believe that a shared understanding of CB fire dynamics, based on empirical data, can strengthen the social component of these linkages and promote effective governance. The current wildfire management system is highly fragmented 74 , and increased social and ecological alignment between actors at multiple scales is necessary for effective wildfire risk governance 14,30 .

Cross-boundary fire activity can contribute to multijurisdictional alignment when fire transmission incentivizes actors to collaboratively manage components of risk that manifest outside their respective ownerships 15 . A broader acknowledgement that CB is inevitable in some fire-prone landscapes will ideally shift the focus away from excluding fire in multijurisdictional settings towards improved cross-jurisdictional pre-fire planning and reducing the vulnerability of high-value assets in and around wildlands 30,31 . Federal agencies like the USFS can provide capacity, analytics, and funding, but given that private lands are where most high-value assets are located and where most CB fires originate, communities and private landowners may be best positioned to reduce losses from CB wildfire.

Now, first of all, it’s kind of hard to parse some of the academic-ese here “will require viewing socio-ecological risk linkages between CB fire sources and recipients as management assets rather than liabilities.” I hope it’s clear to others, they lost me.

“We believe that a shared understanding of CB fire dynamics, based on empirical data, can strengthen the social component of these linkages and promote effective governance.” That’s nice that they believe that, but I’d be curious about the mechanics of how that works. Communities have their own lived knowledge of fires and it’s hard to tell them “some scientists ran some simulations and came up with …. “. And effective governance of HOAs, fire departments, counties, states and feds.. there are many problems at coordination at all scales, but not clear that modeling fire transmissions with their model will be more helpful than all the other fire transmission models that have existed for some time.

“shift the focus away from excluding fire in multijurisdictional settings towards improved cross-jurisdictional pre-fire planning and reducing the vulnerability of high-value assets in and around wildland” Hmm. We have a system that includes both- a very complicated process and alignment of CWPPs, federal lands and and suppression that takes into account all of the above. Perhaps the authors have developed a straw person? or are they saying “leave the federal lands alone and focus on communities?” Which wouldn’t be “all hands all tools”? Or perhaps a change in focus? But then you’d have to articulate what the current focus is and what needs to change.

An alternative risk management framing of this challenge has emerged, starting with the axiom that CB fire transmission is inevitable in fire-prone mixed ownership landscapes and that private landowners and homeowners are the actors best positioned to reduce fire risk to homes and other high-value assets regardless of where the fire starts

I agree that private landowners and homeowners , utilities, ski areas, water providers are best positioned to reduce direct risks. But there are also people (fire suppression folks) working assiduously to keep fires away from infrastructure- and it actually works most of the time (I don’t have a cite, but I can see information on InciWeb). This is a both/and thing. Not sure how the simulations in this paper support changes to the current system. If I’d reviewed it, I would have asked them to draw a logical line between “the system as we see it” “what our data show” and “how we think this information should inform changes.”

And here’s a quote from the OSU piece:

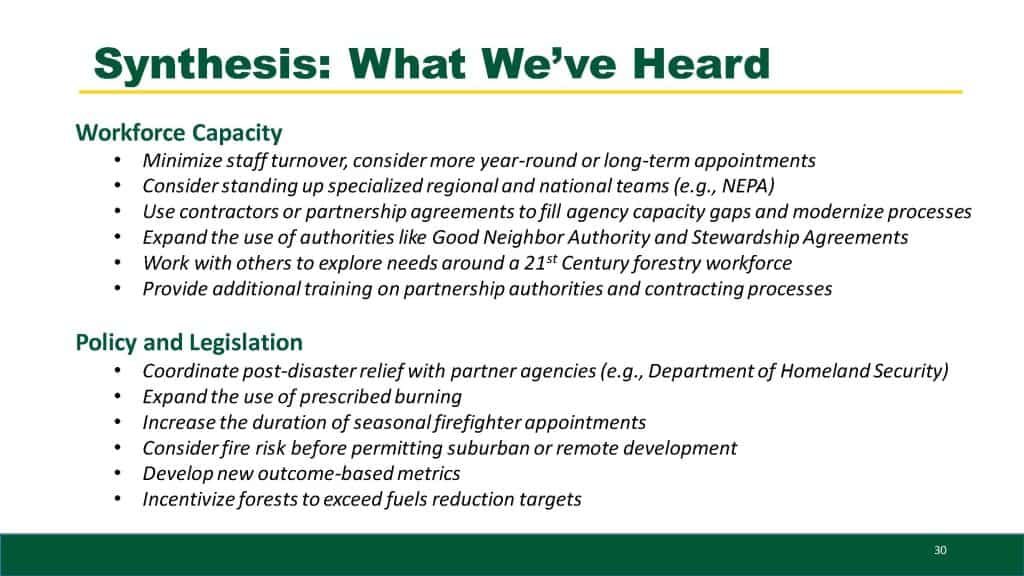

“The Forest Service’s new strategy for the wildfire crisis leads with a focus on thinning public lands to prevent wildfire intrusion into communities, which is not fully supported by our work, or the work of many other scientists, as the best way to mitigate community risk,” Dunn said.

I think this doesn’t take into consideration that that the strategy is the FS chunk of the overall work, of which there are many other bucks going to states and ultimately into communities. They did not say it’s the best way, only what they can contribute. Plus thinning and PB have other desirable attributes in making forests more climate-resilient, so not so much destruction occurs within them in the case of a wildfire. Suppression folks work with a great variety of values at risk that include but are not restricted to communities.

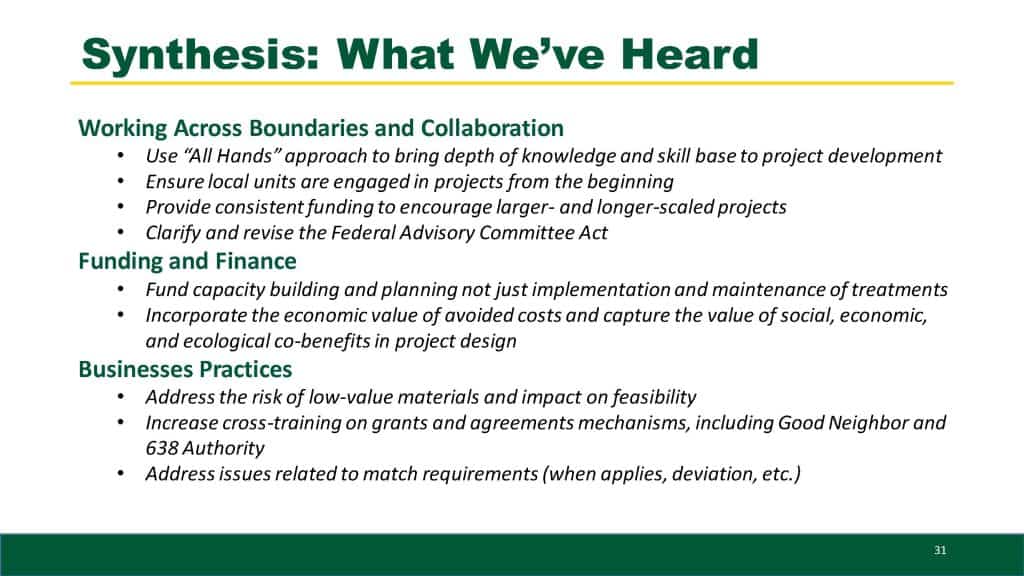

What I would have said based on the data? More fires go into the NFs than come from the NFs based on the data. So working on reducing ignitions and spread before fires get to the FS boundary would be a good idea. But everyone gets to conclude what you want from the data.. what do you conclude?