Chief Moore said many interesting things in his talk at the SAF Convention and in the Q&A’s that followed. In this post, I’ll just talk about what he said about the Ten Year Plan for Fire.

Three caveats: first, the formal announcement of the Ten Year Plan is not out yet, so it may have changed since his talk; and second, I don’t have all the information but tried to piece it together from what he said and may have got something wrong; third, I am really lousy at taking notes. Any mistakes are no doubt mine and not his. People who attended the SAF Convention can watch the recorded presentation and correct me.

********************************

Wildfire is at a crisis level (remember Chief Moore was formerly the Regional Forester for the California Region, so he has been dealing with some of the worst ones).

He said that 98% of the Mendocino had been affected by wildfire in the last two years. In 2021, 2/3 of the town of Grizzly Flats, including the school and the Post Office were burned.

What can we do? Reintroduce low intensity fire and strategically place fuels reduction treatments (and maintain them).

With increasingly bad wildfire behavior, small areas of treatments are not enough to help firefighters get control. So-called “random acts of restoration” aren’t cutting it.

Using the scientific analysis in the Fireshed Registry, they found that 90% of exposure to communities could be reduced with work on 15% of the total land area. But not only is it important to pick the right areas to reduce risk to communities, but also to plan for maintenance of those treatments over time.

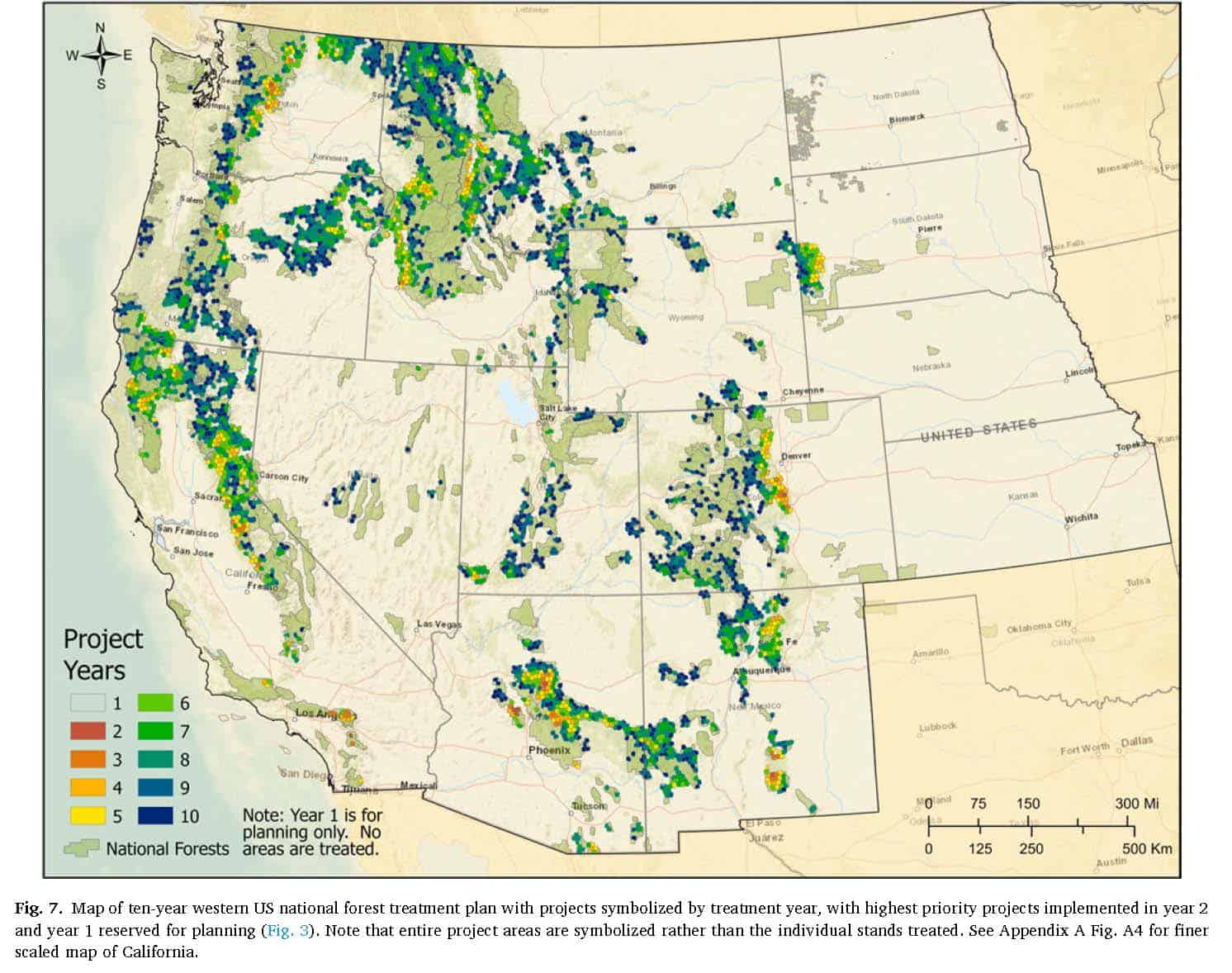

Given that, Chief Moore assigned Brian Ferebee (whom many of us may remember from Region 2) to refine, adjust, and implement the 10 year plan to address the wildfire crisis. It’s a small team with representation from many parts of the Forest Service. They will not be using the old approach- “everybody gets $5”. In the first two years, they will identify projects where the NEPA has already been done and is a critical match with the Fire Registry/Scenario Planning effort. Note that Scenario Planning can be used in a variety of ways at a variety of scales, but I think here it’s a shorthand for a certain way (see Ager and his group’s research) of dealing with fire and fuels planning at the national scale. However, that same group has done scenario planning incorporating a variety of objectives at a variety of scales, as we’ll examine in later posts.

If you haven’t been following this literature, you can see there is some overlap between this and the scenario planning for wildfire risk reduction in this and other papers by Alan Ager and his collaborators at the RMRS Fire Lab. For the purposes of its possible application toward the 10 Year Plan, probably the best paper to read is this one Ager, A. A., C. R. Evers, M. A. Day, F. J. Alcasena, and R. Houtman. 2021. Planning for future fire: scenario analysis of an accelerated fuel reduction plan for the western United States. Landscape and Urban Planning 215:1-12. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104212. Fortunately, it can be accessed openly here.

From the conclusion section:

Our study demonstrated a top down approach to develop a large-scale prioritization to address wildfire risk to developed areas, and an approach to coarsely assess potential wildfire impacts and spatial in tersections with treatments during implementation. The results of the study are being used by the Forest Service to communicate a strategy to ramp up current levels of hazardous fuel treatments to the legislative branches that oversee the agency. The methods can be used by other national scale wildfire management agencies to develop strategic plans, including the assessment of planning risk (Mentis, 2015), i.e., the range of potential wildfire impacts on implementation of strategic risk reduction programs.

Future work can explore the effect of climate change as part of scenario analyses (Star et al., 2016) including assessment of planning risk for fuel treatment and restoration programs (Peterson et al., 2003). For instance, will extreme variability in future wildfire make the use of risk assessment ineffective as a prioritization method for 5–10-year restoration and risk reduction plans? Wider use of scenario planning models by land management agencies is consistent with systems thinking, data analytics, and prescriptive intervention (National Academies of Sciences, 2019), as a way to enhance foresight into natural resource management outcomes, and as part of addressing wildfire challenges in the near term future.

But back to the 10 year plan.. there will also be a monitoring plan to see how it works and to adapt.. plan, implement, monitor and use that information to continue to understand and further improve risk reduction efforts.

Previous efforts to not do the “$5 for everyone” approach have foundered on the shoals of any priority setting mechanism (those left out/delayed aren’t happy).. so it will be interesting to see if this one, with a science base, and because the areas with most exposure and in the early years generally have lots of people (hence votes), will be successful. Given the crisis, though, clearly something different needs to be done.

Finally, the Chief said it would be out soon (at the SAF Convention in early November), so I contacted a source at the FS earlier this week, and the reply was still “a few weeks.” So soon we should see how it comes out.

(Note: this post has been corrected in terms of Ager is at RMRS, and a miscopied quote from the paper and some other edits)