Courtesy photo / CSERC

From the Union Democrat of Mother Lode (Sonora) country in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California.

The Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center in Twain Harte and 14 other conservation groups are urging Randy Moore, the former Pacific Southwest regional forester who is now chief of the U.S. Forest Service, to increase prescribed burning, thinning of surface and ladder fuels, and biomass removal in the face of unnaturally severe megablazes and climate change.

…

“Dear Randy,” the Aug. 2 letter begins, “As many of us have already communicated to you on behalf of our conservation organizations, we applaud your selection as the new Chief of the U.S. Forest Service. Over the 14 years that you served as Regional Forester in Region 5, our groups worked closely with you on a broad range of issues.“With this letter, we urge you — as the new Chief — to apply your leadership so that the Forest Service ramps up the pace and scale of needed actions to effectively address the pressing challenges of high-severity wildfires, climate change, and loss of biodiversity.”

…“We look forward to working with the Forest Service, national and state policymakers, tribes, and diverse stakeholder interests to ensure that taxpayer-funded investments are applied so that agency actions are carefully prioritized and science-based and provide beneficial social and ecological outcomes,” the open letter states. “By focusing on ecological restoration and science-based actions, the Forest Service can continue building trust so that individual national forests can ramp up the scale of forest treatments while minimizing controversy.”

Asked Tuesday to quantify how much conservationists want to see prescribed burning to increase, Jamie Ervin with Sierra Forest Legacy said, “The Forest Service and the state have set a goal of ramping up pace and scale forest restoration including prescribed burning to a million acres a year. That would be a good start. The actual fire regime — calls for more than that.”

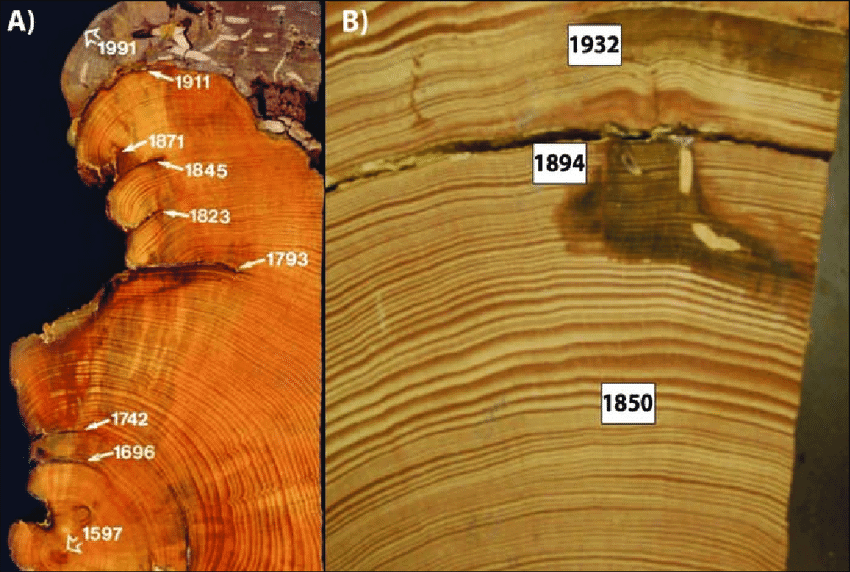

Fire regime refers to the kind of fire and how much fire a particular ecosystem experiences historically, before European settlers arrived, Ervin said.

“Our best estimate is California would have had about 4.5 million acres burning annually,” Ervin said. “From lightning strikes and indigenous people burning intentionally for forest clearing and hunting.”

Prescribed burning right now is about 100,000 acres a year statewide, Ervin said, speaking from Nevada City, about 125 miles north of Sonora. It varies every year. An estimate of prescribed-burn acreage statewide so far this year was not available. Eighteen months ago, the California Air Resources Board reported there were 125,000 acres of prescribed burns statewide in 2019.

Fire is natural in California, and we need fire in the forests, Ervin emphasized. The issue right now is we’re experiencing unnaturally severe fires due to the fact we have suppressed fires for over a hundred years. Conservationists want more forest management, especially significant investment in federal and state prescribed fire programs.

….

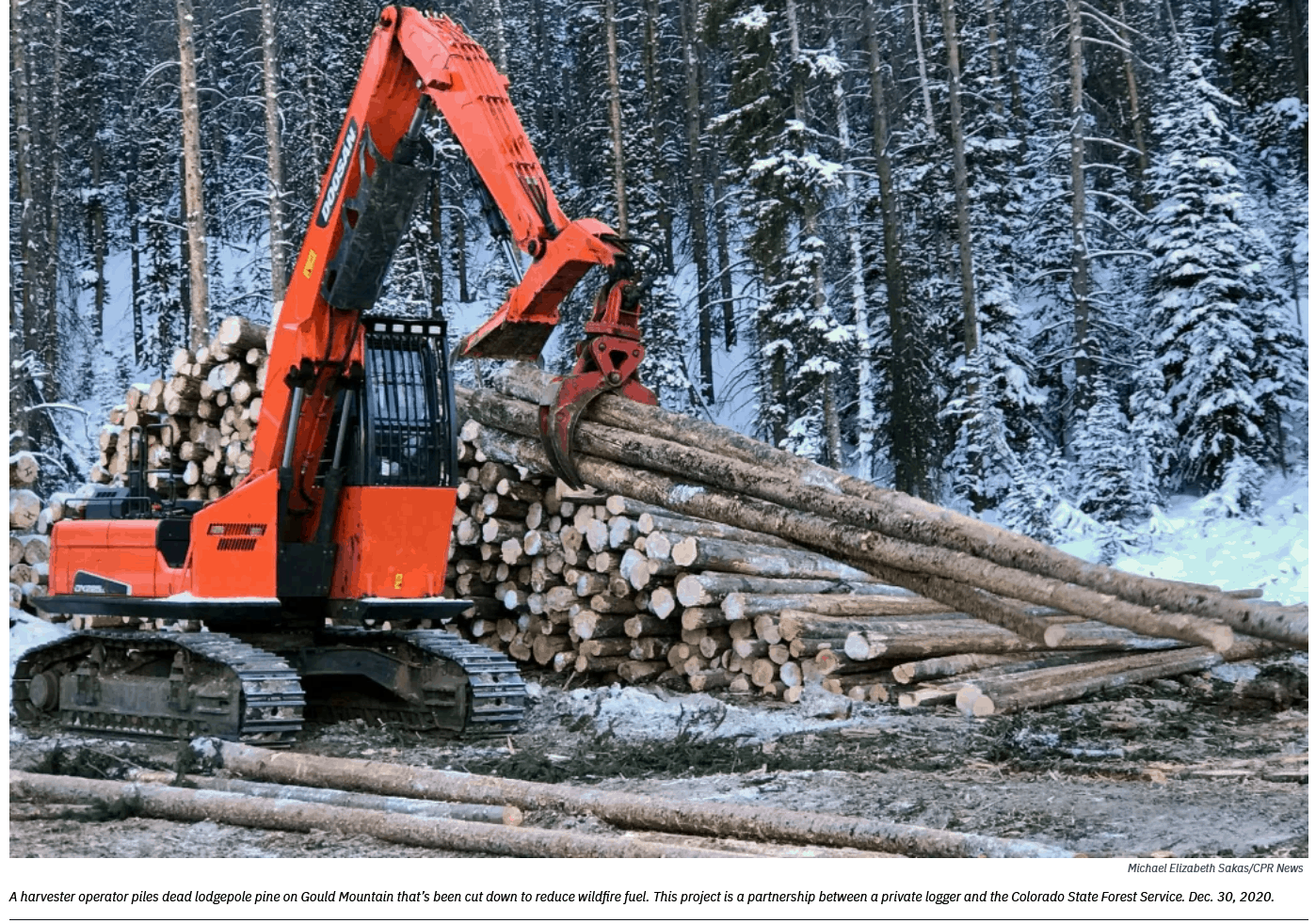

With their letter to Moore, the conservation groups share their collective agreement that it’s essential to significantly ramp up all three kinds of forest treatments — science-based thinning logging in appropriate areas; carefully planned prescribed burning during mild weather times of year; and the removal where economically possible of excess biomass fuels, Buckley said.“This letter is a relatively unique sharing by a variety of conservation groups,” he said. “While our local organizations have been broadly supportive of those treatments, this is a strong sharing of agreement by groups that normally don’t emphasize endorsement of logging or biomass removal.”

Other groups that signed the letter with CSERC and Sierra Forest Legacy were the California Wilderness Coalition, Defenders of Wildlife, the Foothill Conservancy, Friends of the Inyo, the Training and Watershed Center, California Native Plant Society, Sierra Nevada Alliance, the Nature Conservancy, South Yuba River Citizens League, Sierra Business Council, the Tuolumne River Trust, American Rivers, and the Fire Restoration Group.

(my bold)