This is a guest post by Dr. Bob Zybach.

https://rewilding.org/indian-burning-myth-and-realities/

This is probably more of a rebuttal than review. As I was reading through this essay when it was posted here a few weeks ago, I became struck with how familiar it all seemed. Sure enough, when I checked through my old emails, George and I had debated this exact same topic from the exact same perspectives in a series of detailed emails more than 12 years ago — in January 2009.

My first thought was that this was a dated article, but when I checked his post, there was no publication date. That caused me to try for several days to contact him to make certain I wasn’t responding to something he had written long ago, but after no response and noting that a few of his references were from 2020, I decided to continue with my review.

The problem is that Wuerthner has written something debatable in nearly every single paragraph, and there are a whole lot of paragraphs. Dozens of uncited opinions and questionable statements are presented as “facts,” supported by cherry-picked references and superficial citations to important materials that he seems unfamiliar with. The exact same problems I was pointing out when we were corresponding in 2009.

Wuerthner describes “8 Major Issues” with the “Indian Burning Myth” that he lists at the outset of his essay. In this regard, these do seem to be representative of the general thinking that still pervades his (and others) thinking on these issues today. So, my strategy in addressing these issues is to quote him directly on representative statements (which I put into italics), and then offer my own perspective or criticism on a mostly point-by-point basis. Sorry for the length. It was a long article with lots of misinformation.

Wuerthner’s “8 Major Issues”

- The claim that Indian burning precludes large fires feeds into the “fuels is the problem” narrative, which is increasingly discredited, as large wildfires in fact are driven by extreme climate weather.

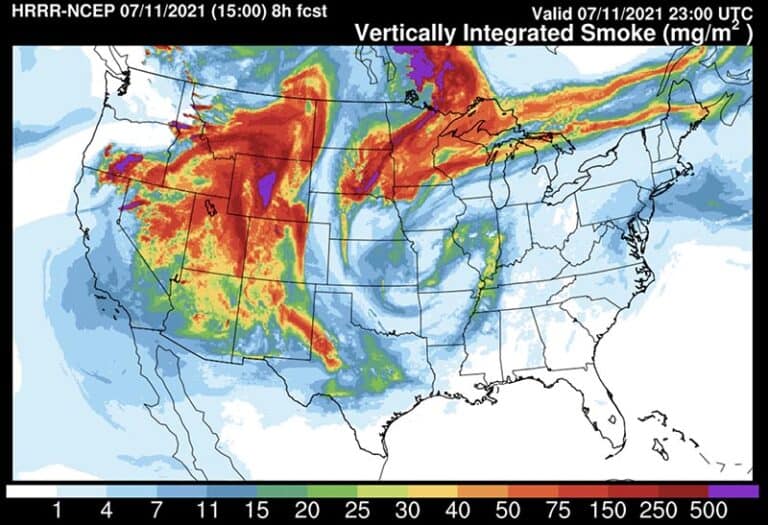

I am not sure what “climate weather” is, but climate is a mathematical average of weather measurements over time — typically 30 years or more. When I discussed this issue with George in 2009, he said it was a “cheap shot” when I pointed out that wildfires can’t take place in a desert or on a lake, no matter the weather, because of lack of fuels. However, that argument still stands. Fuels are needed. How those fuels burn is determined in large part by the weather, but a large fire can create its own weather — including gale-force winds, “pyronadoes,” cumulus clouds, and even rain.

One thing that consistently weakens Wuerthner’s arguments are his uses of phrases such as “in fact,” which he seems to confuse with “in my opinion,” or something of that nature when it comes to qualifying statements. In mitigating wildfire effects, fuels are the main problem that can be addressed, along with human sources of ignition. We can’t control the weather, no matter how many “carbon credits” we might purchase. Topography is a given, and wildfire sources of ignition are mostly caused by people (year-round) or lightning (seasonal in some locations), with volcanoes and spontaneous combustion occasionally contributing to the mix.

- All large fires are driven by climate and weather conditions which include drought, low humidity, high temperatures, and high winds.

This reminds me of the joke that “all absolute statements are false.” This is an absolute statement in which the word “driven” takes on a much more general definition than when the word is usually associated with wildfire. Climate is an average and does not drive wildfires — I can only guess why George and others keep making this statement (“politics” and “potential funding” come to mind).

“All large fires” are not “driven” by drought, are usually driven by high winds (depending on fuels), and typically take place during weather conditions that include high temperatures and low humidity. Often, large fires do take place during periods of seasonal or prolonged drought. Heavy spring rains — not drought — can result in increased flash and ladder fuels that readily burn during seasonal dry spells.

- These conditions have always existed, and large blazes have always occurred despite Indigenous burning. However, they are being exacerbated today by human-caused climate warming.

Yes, these weather conditions have existed for a very long time (maybe not “always”), and large fires have likely existed from the time of the first dry land vegetation, volcanoes and lightning, but there is zero scientific evidence that they are being “exacerbated today by human-caused climate warming.” Putting aside the difficulty of warming a climate, it needs to be made clear that climate change modelers have been consistently wrong for the past 30+ years in their prophesies of “climate catastrophe” and its “proof” by increased numbers and sizes of wildfires, Florida underwater, melting glaciers, and widespread famine. Wildfires have been worse, as scientifically predicted since 1986, but those predictions have been based almost entirely on unmanaged fuels on federal lands, not climate.

- Indigenous burning resulted primarily in localized fuel reductions but seldom affected the larger landscape.

This is silly, and possibly even a little racist. George lives, or has lived, in Eugene, Oregon, which is in the southern portion of the Willamette Valley. This Valley is more than 3,000,000 acres in size and was entirely formed and maintained by Indian burning practices for thousands of years. Due south is the Umpqua Valley, with the Bear Creek Valley then extending further south nearly to the California border — and both with similar fire histories as the Willamette Valley. People usually settle in valleys, around lakes, along the coast, and at the mouths of creeks and rivers. Fire travels uphill and on the wind — human-caused fires will often get out of control, even if it is Indians that are setting them, if fuels exist along the hillsides. These fires, whether set purposefully or by accident, invariably “affect the larger landscape,” by definition.

And where is George getting the idea that pre-European peoples clustered into “localized” settlements and only had a rudimentary understanding of fire? Obsidian tools that originated in present-day Oregon were recently discovered at an underwater archaeological site in the Great Lakes. Historical Indian trade routes existed the entire length of the Columbia and Mississippi Rivers and numerous foot trails crossed the Rockies, connecting the two great basins. Indians traveled and traded extensively for thousands of years and mostly used fire expertly on a daily basis — same as people everywhere.

- There is historic, scientific, ecological, and evolutionary evidence that challenges the Indian burning narrative.

I’m sure that’s true, but the basic function of science (and probably ecology, too) is to challenge prevailing assumptions and stated hypotheses — so that would be normal and expected. Not too sure of the “historic” information that is being referenced, or what “evolutionary evidence” might exist. Not sure how this statement even qualified as a “Major Issue.”

- Large high severity fires are not “destructive” but essential to many healthy forest ecosystems.

Now we’ve devolved to semantics. Unfortunately, these fires are, indeed, “destructive” by almost any definition. Wildlife are killed, the air is fouled, homes are sometimes burned, and the results are often determined to be ugly and increasingly hazardous for years to follow. Then we have George’s additional opinion that these events are somehow “essential” to whatever he thinks “healthy forest ecosystems” are. Those are known as “value statements” that typically vary from person to person. They are not facts in any sense of the word, just overstated opinions — which, in my experience, many, many people do not agree with, including a significant number of forest scientists and forest managers.

- Implementation of a significant prescribed burning program has many obstacles.

That is true. I’m not sure there is any debate on this point.

- The way to protect homes is to start from the home outward, not to “treat” forests at the landscape scale.

Another of George’s opinions. Flames, sparks, and burning debris can travel hundreds of feet and miles in advance of a forest fire. A well maintained and irrigated homesite should largely be unaffected by these sources of ignition — unless the home is on the edge of a forest, then the formula changes dramatically. One size does not fit all, and all generalities remain false.

CHERRY-PICKING

After listing these “8 Major Issues,” Wuerthner then goes into lengthy examples and discussions as to why they are so important. Unfortunately, he uses a number of devises to support these assertions that only weaken his conclusions. His writing habits — that include “cherry-picking” the data, superficial references, and stating personal opinions as universal facts — should make the reader suspicious.

In 2009 I suggested that Wuerthner could balance his assertions by reading Robert Boyd’s book on the fire history of the Willamette Valley and Kat Anderson’s book, Tending the Wild, in order to become better informed on this issue. He replied that he would do so and thanked me for the suggestion, but neither one is cited in his essay or listed in his Reference section, 12 years later. My PhD dissertation is on the exact same topic and it’s not listed either — not that I expected it to be.

There are known experts on the Indian burning history of the US, and George is familiar with who they are. But they are not cited in his work, and further weaken it as a result. If he was serious about this topic, he would become far more familiar with the writings of Stephen Pyne, Robert Boyd, Henry Lewis, Omer Stewart and Kat Anderson. Vale, Knox and Whitlock need to be considered in context to these recognized experts in the field, not as the actual voices of “science” on this issue.

Wuerthner also claims that the pollen record is of importance. I agree, but he continues:

If Indigenous burning was so widespread as to influence landscape-scale vegetation, we would expect to find abundance pollen from species favored by frequent, low severity fires. For the most part, except in the immediate area around villages, this evidence does not exist.

More fiction, possibly based on the research of Whitlock or one of her students. Again, if Wuerthner wants to cite a single source to support his perspective, he should reasonably put that perspective in context to the established experts in the field. In that regard, Henry Hansen’s work has been available online since 2002,

SUPERFICIAL CITATIONS

The idea that tribal burning impacted the broad landscape is also asserted by some scholars (e.g. Williams, G.W. 2004), but often with scant evidence to back up these claims except for “oral traditions” of Native people.

Gerald Williams is an expert on Indian burning history and has written extensively on the topic. He never claimed to depend on “oral traditions” for his research — Wuerthner is just making that up to trivialize this work. I’m guessing he hasn’t bothered to actually read Williams’ article, or much else of his other writings on this topic.

Most “evidence” for the widespread influence of indigenous burning is based on oral tradition which is notoriously subject to variation of interpretation and misinterpretation.

This is just bullshit, and Wuerthner must know that. My MAIS degree from Oregon State University was in oral histories. These are not true statements and grossly misrepresent both Williams’ and my own research. My PhD study at OSU study focused on Indian burning and catastrophic wildfire patterns of the Oregon Coast Range, from 1491 to 1951. It has been readily available online for nearly 20 years, yet Wuerthner chooses to ignore this research and simply make things up, or else cite sources of dubious accuracy:

Here are a few sentences from my PhD Abstract, which in its entirety only takes a couple of minutes to read:

Archival and anthropological research methods were used to obtain early surveys, maps, drawings, photographs, interviews, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) inventories, eyewitness accounts and other sources of evidence that document fire history. Data were tabulated, mapped, and digitized as new GIS layers for purposes of comparative analysis. An abundance of useful historical evidence was found for reconstructing precontact vegetation patterns and human burning practices in western Oregon.

In addition to apparently being unfamiliar with Williams actual writing and misrepresenting his research, Wuerthner does the same thing with another expert on the topic, John Leiberg, and his USFS report on SW Oregon forests in 1899. Here is Wuerthner’s entire reference and citation for Leiberg:

Early timber surveys also record large high severity fires (Leiberg, J. B. 1903).

I am actually very familiar with Leiberg’s work (I don’t think he was ever aware of the term “high severity fire”) and developed an unfinished report on his detailed 1899 report in which I transcribed and organized his statements on old-growth, wildfires, logging, forest history, reforestation and Indian burning, with minor commentary, and put it online as a draft report in 2006. http://www.orww.org/History/SW_Oregon/References/Leiberg_1899/

Here are some direct quotes:

(p. 249) The forest floor in the [“yellow-pine”] type is covered with a thin layer of humus consisting entirely of decaying pine needles, or it is entirely bare. The latter condition is very prevalent east of the Cascades, where large areas are annually overrun by fire. But even on the western side of the range, where the humus covering is most conspicuous, it is never more than a fraction of an inch in thickness, just enough to supply the requisite material for the spread of forest fires.

(p. 277) The largest burns directly chargeable to the Indian occupancy are in Ts. 30 and 31 S., Rs. 8 and 9 E. In addition to being the largest, they are likewise the most ancient. The burns cover upward of 60,000 acres, all but 1,000 or 1,100 acres being in a solid block. This tract appears to have been systematically burned by the Indians during the past three centuries [ca. 1600 to 1855]. Remains of three forests are distinctly traceable in the charred fragments of timber which here and there litter the ground.

FACTS & OPINIONS

Finally, although Wuerthner’s cherry-picking and misrepresentations make his conclusions suspect, his habit of stating his personal opinions as if they are actually facts only serves to further erode his credibility. Here are some examples, with occasional commentary:

The second highest biodiversity, after old-growth forests, is found in the snag forests with down wood that results from these blazes. These high severity habitats would not exist if such Indigenous burning were as widespread as advocates suggest.

Not sure where George is getting his “biodiversity” measures from (or why they are important to him), but he is apparently unfamiliar with tropical forests, the ocean, and deciduous woodlands.

Most cultural burning, like the prescribed fires set today by state and federal agencies, was practiced in the spring and fall when fire spread was limited by moist fuels, high humidity, cool temperatures, and when winds are calm.

Actually, at least in western Oregon, most Indian burning took place in late summer or fall (“fire season”), as documented by many, many eyewitness accounts. More misinformation, based on personal bias.

Native people were wise enough not to purposely set fires in the middle of extreme fire weather. Setting a blaze under conditions with variable high winds and during a drought would be a recipe for disaster because it would lead to uncontrollable fires that would threaten villages and life.

Bullshit. Wuerthner’s biases do not equal “Indian wisdom.” More self-serving fiction.

For instance, in Oregon’s Willamette Valley most large trees were established after large, high severity fires that occurred long before Euro-American influences on native populations. The 1865 Silverton Fire burned more than a million acres of the western Cascades. The 1853 Yaquina Fire burned nearly a half-million acres.

Jeez. There is zero evidence that the scattered large oak and Douglas fir documented by Euro-American settlers in the Willamette Valley followed a “large, high severity fire.” Not sure where Wuerthner got this nonsense. The “million-acre” Silverton Fire is one of the “myths” that Wuerthner says he is challenging. This became a popular fiction at some point and seems to be referring to one or more Civil War-era wildfires in the Silverton area of western Oregon that likely totaled no more than 100,000 acres. I have personally completed thousands of acres of reforestation projects in the Yaquina burn. This fire took place in 1849 or 1850 at the latest and was expanded in size with a second (or third) major fire in 1868. I studied this fire on-and-off for 30 years and my research is summarized in my dissertation.

Another study found that the mean fire interval in Oregon’s Coast Range was 230 years and the presence of fire-sensitive species like Sitka spruce indicates a lack of frequent fire (Knox and Whitlock 2002).

This is another instance where Knox and Whitlock (and Wuerthner) show their lack of understanding of actual western Oregon fire history. The “230-year fire interval” is total nonsense and difficult to determine who made this up. The famous “Six-Year Jinx” of Tillamook Fires took place in 1933, 1939, 1945, and 1951 — following major fires in the 1890s and 1918. The 1868 Coos Fire followed two or three major events in the 1700s, at least one major fire in the 1840s, and was followed by the 1879 “Big Burn.” There are more examples.

Even if prescribed burning could reduce large blazes (which would not be good for forest ecosystem health), multiple problems would result if prescribed burning were to ramp up significantly.

Apparently, George wants his readers to believe that “large blazes” are “good” for “forest ecosystem health,” whatever that is. His arguments and supposed “evidence” remain unconvincing and unlikely.

SUMMARY

Perhaps the biggest problem with the “Indigenous burning will preclude large blazes” argument is that it feeds into the narrative that “fuels” are driving the large fires we see around the West. To reiterate, large fires are and have always been primarily climate-weather driven events.

Fuels do not drive large blazes. Climate/weather does.

I still don’t know what “Climate/weather” is, but I do know an anti-active management agenda when I see one. I would caution students to avoid citing Wuerthner as any kind of authority on fire history, forest management, or wildfire mitigation.