No wonder people are confused about “treatments should focus near communities.” I think the discussion of the Crystal Clear project was helpful. I’m beginning to think “in some forests, people do treatments for a variety of reasons (forest health, resilience, HRV) that includes designing places for firefighters to do backfires and use other tactics to reduce negative effects of wildfires.” This is called “landscape resilience” in the Cohesive Strategy.

I’m a fan of FACNET The Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network (#EnvironmentWithoutEnemies) and they have a quote on their website.

We realized that there isn’t a line where fire adapted communities stop and fire resilient landscapes begin.

FOREST SCHAFER, CALIFORNIA TAHOE CONSERVANCY

Here’s an interview with the Dean of the OSU School of Forestry about Oregon fires, by the Portland Tribune. Thanks to RVCC, I found this link in their monthly newsletter. Below is an excerpt, but there are interesting ideas about what he thinks the State or Oregon should do.

Eastside forests are a little more straight forward. … The west side is more tricky — I don’t think we can thin or burn our way out of these types of fires. We need better community planning. More upfront, preventative, mitigation efforts are needed. More of an investment upfront for pre-planning on a landscape basis cross-boundary. We have a planning process that has worked in the south-central part of the state. (Click here to see it.)

This is an interesting document: “This guide describes the process the Klamath-Lake Forest Health Partnership (KLFHP) has used to plan and implement cross-boundary restoration projects to achieve improved forest health conditions on large landscapes.”

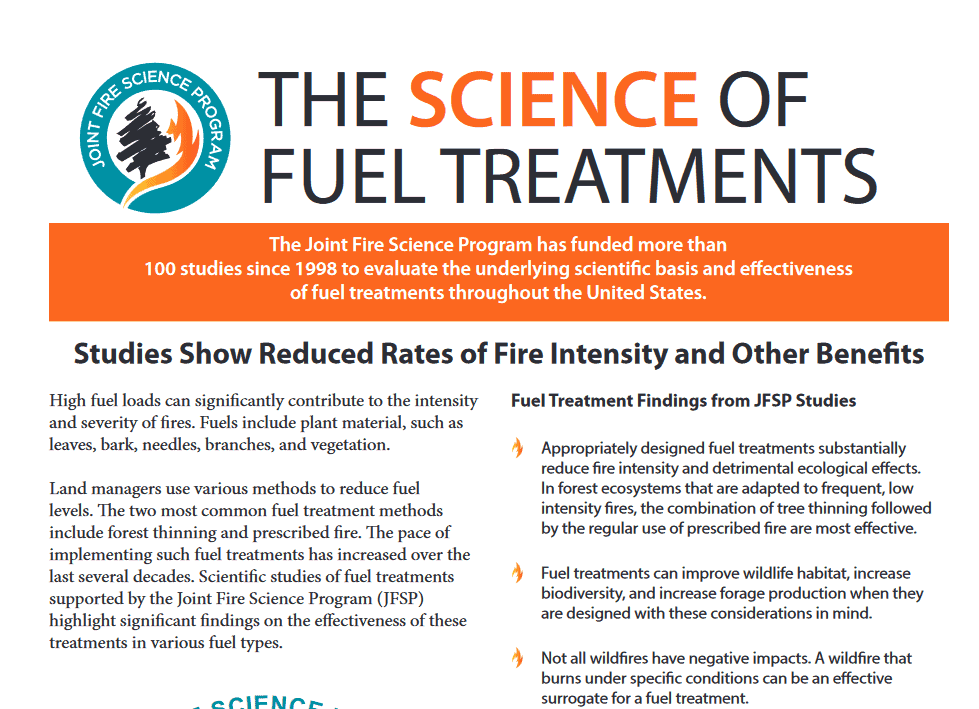

Wildfires today are larger and more severe, starting earlier, ending later, and resulting in loss of homes, forests, and other resources. Past and current

management practices, including fire exclusion, have left forests in dry regions stressed from drought, overcrowding, and uncharacteristic insect and disease

outbreaks. Compounding the problem is the fact that humans cause 84 percent of all wildfires in the United States. These human-caused fires account for 44 percent

of the total area burned and result in a fire season that lasts three times longer over a greater area (Balch et al, 2017). The increase in size and severity of wildland fires is causing ecological, social, and economic damage. The departure from historic fire patterns is also having an impact on water, wildlife habitat, stream function, large and old tree structure, and soil integrity.Wildfires are affecting communities across the West. The 2017 fire season again illustrated the risk of wildfire to communities large and small. Subdivisions

in urban areas have become a fuel component, burning from house to house similar to how crown fires burn from tree to tree. Economically, wildfires burn valuable

infrastructure and timber, make recreation and tourism unappealing, and can have direct impacts to municipal water supplies (Diaz, 2012).In 2009, the National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy (https://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/strategy/thestrategy.html) was developed as a strategic push to encourage collaborative work among all stakeholders across all landscapes to use best scientific principles and make meaningful progress towards three goals:

1) Resilient landscapes

2) Fire-adapted communities

3) Safe and effective wildfire response

This strategy establishes a national vision for wildland fire management, describes wildland fire challenges, identifies opportunities to reduce wildfire risks, and

establishes national priorities focused on achieving these national goals.”

Here’s a link to a video called Timber Crater 6 Fire- A Fuel Treatment Success Story that was on the Klamath-Lake Forest Health Partnership website. I think it does a good job of explaining the interaction between fuel treatments and suppression tactics.

So when people say “focus on the WUI for fuel treatment” perhaps they mean:

A. Focus on projects that are solely for fuel treatment to protect communities and not landscape resilience.

B. Funding – the hazardous fuel $ agencies have should be only/preferentially for x miles from (houses, roads, powerlines..?)

C. Priority -“do not do PB or WFU or mechanical treatments anywhere else until all the fuels treatment work around communities is done”

D. Just don’t- “don’t do PB, WFU or MT at all away from communities.”

E. PB and WFU are OK, because “fire is good for ecosystems” but not mechanical treatment (away from communities).

F. WFU is OK, but PB and MT not (away from communities).

Hopefully with these ideas laid out, we can look deeper into what people mean. Do you have any other possibilities to add?