No Threatened Status for the California Spotted Owl. Current protections remain. The article is a good read, with some of the “usual suspects”.

http://www.calaverasenterprise.com/news/article_a866d476-14d2-11ea-b7e0-7b830918c726.html

The Smokey Wire : National Forest News and Views

Community Sourced, Shared and Supported

No Threatened Status for the California Spotted Owl. Current protections remain. The article is a good read, with some of the “usual suspects”.

http://www.calaverasenterprise.com/news/article_a866d476-14d2-11ea-b7e0-7b830918c726.html

Well, not exactly, maybe. This could be a good example of how to get the public involved early enough in the process for timber harvest decisions that the locations have not been determined yet. But consider that the decision-maker is the same one who applied “condition-based” NEPA analysis to the Prince of Wales area of the Tongass, which has ended up in court.

Bitterroot National Forest Supervisor Matt Anderson has added a new “pre-pre-scoping” stage to the process, not part of the traditional process in which a set of options is presented to the public for review and analysis.

The new approach is meant to get the public involved prior to coming up with any specific actions being planned for any specific location.

That much I like the sound of.

“There is confusion,” said Anderson. “It’s hard for the public to get involved. We are asking ‘What do you want to see? What’s your vision?’” He said the agency was “starting at the foundational level, not any particular location.” He said it was important to get to those particulars but the way there was to first describe the “desired future condition that we want and then look at the various ways we can achieve it.”

Asked about the fact that the current Forest Plan describes a desired future condition for the Bitterroot Front that involves returning it to primarily a Ponderosa pine habitat with little understory, Anderson said that is in the current plan, but that the plan is about 30 years old. He said a lot has changed in that time on the ground. There have been lots of fires and areas where no fires have occurred, and the fuel load has gotten extremely high. He said current conditions need to be assessed and they were currently compiling all the maps and other information they need to get an accurate picture of what is on the ground today in the project area.

This should raise a concern about how this process relates to forest planning, since forest plans are where decisions about desired conditions are made. However, old forest plans typically didn’t provide desired conditions that are specific enough for projects, so that step has occurred at the project level. Under the 2012 planning rule, specific desired conditions are a requirement for forest plans, but the Bitterroot National Forest is not yet revising its plan. Whatever desired conditions they come up with should be intended as part of the forest plan, and the public should be made aware of this. If the new decision is not consistent with “Ponderosa pine habitat with little understory,” they’ll need an amendment to be consistent with the current plan. (I’d add that changes in the on-the-ground conditions over the last 30 years shouldn’t necessarily influence the long-term desired condition.)

“The Tongass is so different than the Bitterroot,” said Anderson. “There is not much similarity. I’m not trying to replicate that process here. It was a conditioned-based process up there. It’s like comparing apples to oranges.” In reference to conditioned-based projects, he said, “One difference with this project is that some of that will be pre-decision and some of that will be in implementation. We are trying to shift some of the workload to the implementation stage.”

He said they have a slew of options, from traditional NEPA, to programmatic NEPA to condition-based NEPA “and we are trying to figure it out.”

He insists that the NEPA process will be followed with the same chance for public comment and involvement on every specific project that is proposed in the area.

There’s some ambiguous and possibly inconsistent statements there. Condition-based NEPA seeks to avoid a NEPA process “on every specific project.” I could also interpret shifting workload to “pre-decision” and “the implementation stage” is a way to take things out of the NEPA realm.

And then there’s this:

In response to the notion that the huge project is being driven by timber targets and not health prescriptions, Anderson said that the Regional Office had set some timber targets for different areas of the region, but that those targets were not driving the analysis. “This project has nothing to do with meeting any target,” said Anderson.

This feels a little like “There was no quid pro quo.” Would timber harvested from this project not count towards the targets? (I’d like to see targets for achieving desired conditions.) All in all this project would be worth keeping an eye on.

(By the way, here’s the latest on Prince of Wales.)

This started out as a very long comment on the previous article on Utah. I was deeply involved in the development of the Colorado Roadless Rule. That is, until one morning I came into work and was rather unceremoniously removed, at the behest of parties unknown, for reasons unknown (at least to me). To be honest, the whole episode was somewhere between unceremonious and ignominious. Despite that blip on the screen, I feel as if I have earned Roadless Geekhood status. Nevertheless, I could easily be wrong, so in the interests of explaining this, I’d appreciate any corrections.

Most Roadless discussions in the press and many public comments are at a pretty abstract level. “State opens up roadless areas to unmitigated logging” and so on. Even our own colleague, Dave Iverson, in an op-ed in the Salt Lake Tribune wrote “I won’t attempt to guess Herbert’s true intentions for bringing this petition to the Forest Service. I do know it is not a sincere or comprehensive attempt to combat wildfires.”

Yet the 2001 Rule, as one of its authors Chris Wood once said “was not written on stone tablets.” As a general rule, any policy should have some kind of feedback mechanism for improvement. For example, in Colorado we had acres that weren’t really roadless in IRA’s and areas that should have been in IRA’s that weren’t. Swapping them around seemed like a good idea.

I am generally a fan of the 2001 Rule and think it was a great policy step forward (even in the early 90’s the idea was an alternative within the RPA Program). Nevertheless, there were things in it that fit those days, but perhaps not today, as well as they might.

When we think about fuel treatments and roadless areas, we have to think about two things. The first is tree cutting and the second is removal. What does the 2001 Rule say?

Exception for cutting:

(ii) To maintain or restore the characteristics of ecosystem composition and structure, such as to reduce the risk of uncharacteristic wildfire effects, within the range of variability that would be expected to occur under natural disturbance regimes of the current climatic period;

In Colorado, we generally thought that that would work for ponderosa pine, but not so much for dead lodgepole (of which we had many acres). What is the “current climatic period?” Isn’t that influenced by climate change? If so, then what is a “natural disturbance regime” for an unnatural and unknown going forward climate? Or is it the past climate? But that’s not what the regulations says.

And isn’t the whole thing a little dishonest when the purpose and need is really to provide a safe space for suppression folks to work and to change fire behavior? Through at least five years of discussions, we came to the conclusion that this was too fuzzy and could lead to litigation, and that the WUI needed something more specific. Many discussions of WUI definitions took place, as might be imagined.

As part of the negotiations, Colorado Roadless acres were divided into an “upper tier” and “non-upper tier”. Public comment was received on the mapping and the restrictions in each tier.

Here’s what the Colorado Rule says:

CFR part 223, subpart A.

(c) Non-Upper Tier Acres. Notwithstanding the prohibition in paragraph (a) of this section, trees may be cut, sold, or removed in Colorado Roadless Areas outside upper tier acres if the responsible official, unless otherwise noted, determines the activity is consistent with the applicable land management plan, one or more of the roadless area characteristics will be maintained or improved over the longterm with the exception of paragraph (5) and (6) of this section, and one of the following circumstances exists:

(1) The Regional Forester determines tree cutting, sale, or removal is needed to reduce hazardous fuels to an at-risk community or municipal water supply system that is:

(i) Within the first one-half mile of the community protection zone, or

(ii) Within the next one-mile of the community protection zone, and is within an area identified in a Community Wildfire Protection Plan.

(iii) Projects undertaken pursuant to paragraphs (c)(1)(i) and (ii) of this section will focus on cutting and removing generally small diameter trees to create fuel conditions that modify fire

behavior while retaining large trees to the maximum extent practical as appropriate to the forest type.

(2) The Regional Forester determines tree cutting, sale, or removal is needed outside the community protection zone where there is a significant risk that a wildland fire disturbance event could adversely affect a municipal water supply system or the maintenance of that system. A significant risk exists where the history of fire occurrence, and fire hazard and risk indicate a serious likelihood that a wildland fire disturbance event would present a high risk of threat to a municipal water supply system.

(i) Projects will focus on cutting and removing generally small diameter trees to create fuel conditions that modify fire behavior while retaining large trees to the maximum extent practical as appropriate to the forest type.

(ii) Projects are expected to be infrequent.

(3) Tree cutting, sale, or removal is needed to maintain or restore the characteristics of ecosystem composition, structure and processes. These projects are expected to be infrequent.

Next post: Removal of Cut Trees and Temporary Roads

If someone knowledgeable about Idaho Roadless would tell us how fuel treatments are handled in the different themes, that would add to our discussion.

I wouldn’t have thought that one is a substitute for the other, and maybe this suggests that Utah defined its problem wrong initially. But they’re happy enough with the way their Shared Stewardship agreement is working that they have put their roadless rule proposal on a back burner. At least some greens seem happy, too, and least those concerned about roadless areas. Priority-setting, within the framework of a forest plan, is one thing that I think lends itself to collaboration.

Amid debate about state-specific exemptions to the Roadless Rule, Congress created the capacity to negotiate “stewardship contracts” ranging up to 20 years with states in the 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act. It allows the Forest Service to rely on “state’s guidance for designing, implementing, and prioritizing projects geared toward reducing the risks of damaging wildfires and promoting forest health.”

Wilderness Society Senior Resource Analyst for National Forest Policy Mike Anderson said conservationists are encouraged by what Shared Stewardship agreements could foster in addressing critical needs. “Working side-by-side to identify the major risks and implement projects that are actually going to make a difference on the land is something conservationists, I think, can generally can support,” he said. “We think it is good.”

(Utah Public Lands Policy Coordinating Office lead counsel) Garfield said under the agreement, projects “can happen, and are occurring, within and without the roadless area, when necessary.” ‘The existing rule provides a lot of exceptions that the Forest Service can use for forest restoration,” he said. “The Forest Service wasn’t using those” exceptions in many cases. Garfield said PLPCO will be watching closely over the next four years to see if the Shared Stewardship agreement works out before withdrawing its petition. “I won’t say everything we hoped to accomplish under a state-specific Roadless Rule will be achieved under the Shared Stewardship agreement,” he said, “but a lot of progress is being made.”

(One error in this article – the Idaho and Colorado state roadless rules have been approved.)

In a small gesture for accuracy in media, I took the liberty of retitling Shellenberger’s November 4 Forbes piece for our TSW post. Here’s the link.

Let’s look at this article in light of what we discussed yesterday. Climate and wildfires both have their own sets of experts and a variety of disciplines, each of which having different approaches, values and priorities. I’m not saying that studying the results of climate modelling is entirely a Science Fad, but listen to Keeley here:

I asked Keeley if the media’s focus on climate change frustrated him.

“Oh, yes, very much,” he said, laughing. “Climate captures attention. I can even see it in the scientific literature. Some of our most high-profile journals will publish papers that I think are marginal. But because they find climate to be an important driver of some change, they give preference to them. It captures attention.

And the marginal ones are funded because.. climate change is cool (at least to “high-profile” journals, which have their own ideas of coolness). And who funds it? The US Government. Me, I would give bucks to folks for, say, physical models of fire behavior,(something that will help suppression folks today)rather than attempting to parse out the unknowable interlinkages of the past. But that’s just me, and the way the Science Biz currently operates, neither I nor you get a vote.

Note that the scientists quoted, (Keeley, North, and Safford) in this piece are all government scientists. Keeley and North are research scientists while Safford appears to be a Regional Ecologist (funded by the National Forests), so if we went by the paycheck method (are they funded by R&D?) Safford would have to get permission from public affairs, while Keeley and North would not. On the other hand, Safford has published peer-reviewed papers, so perhaps he should not have to ask permission? Even with permission requirements, though, they seem able to provide their expertise to the press.

Keeley talks about the fact that shrubland and forest fires are different beasts, and sometimes get lumped together in coverage. Below is an interesting excerpt on the climate question.

Keeley published a paper last year that found that all ignition sources of fires had declined except for powerlines.

“Since the year 2000 there’ve been a half-million acres burned due to powerline-ignited fires, which is five times more than we saw in the previous 20 years,” he said.

“Some people would say, ‘Well, that’s associated with climate change.’ But there’s no relationship between climate and these big fire events.”

What then is driving the increase in fires?

“If you recognize that 100% of these [shrubland] fires are started by people, and you add 6 million people [since 2000], that’s a good explanation for why we’re getting more and more of these fires,” said Keeley.

What about the Sierras?

“If you look at the period from 1910 – 1960,” said Keeley, “precipitation is the climate parameter most tied to fires. But since 1960, precipitation has been replaced by temperature, so in the last 50 years, spring and summer and temperatures will explain 50% of the variation from one year to the next. So temperature is important.”

Isn’t that also during the period when the wood fuel was allowed to build due to suppression of forest fires?

“Exactly,” said Keeley. “Fuel is one of the confounding factors. It’s the problem in some of the reports done by climatologists who understand climate but don’t necessarily understand the subtleties related to fires.”

So, would we have such hot fires in the Sierras had we not allowed fuel to build-up over the last century?

“That’s a very good question,” said Keeley. “Maybe you wouldn’t.”

He said it was something he might look at. “We have some selected watersheds in the Sierra Nevadas where there have been regular fires. Maybe the next paper we’ll pull out the watersheds that have not had fuel accumulation and look at the climate fire relationship and see if it changes.”

I asked Keeley what he thought of the Twitter spat between Gov. Newsom and President Trump.

Sharon’s note: I don’t know Keeley, but I thought he handled this very well, considering it’s not really a question about his research. The above italics are mine.

“I don’t think the president is wrong about the need to better manage,” said Keeley. “I don’t know if you want to call it ‘mismanaged’ but they’ve been managed in a way that has allowed the fire problem to get worse.”

What’s true of California fires appears true for fires in the rest of the US. In 2017, Keeley and a team of scientists modeled 37 different regions across the US and found “humans may not only influence fire regimes but their presence can actually override, or swamp out, the effects of climate.” Of the 10 variables, the scientists explored, “none were as significantly significant… as the anthropogenic variables.”

It’s encouraging to think that research shows that fire suppression has an big impact on fires. Otherwise, we’d have to give it up because fire suppression isn’t “based on science” 😉

Here’s how it works: Investors buy into the bond, and the money is drawn as needed for forest restoration work. This includes thinning, strategic backfires and other rehabilitation. In this first case, it was a $4 million bond with money from CSAA Insurance, Maryland-based investment firm Calvert Impact Capital, The Rockefeller Foundation, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

The investors are paid back over five years, with 4% interest, by those who benefit from the work and have contracted with Blue Forest, like the U.S. Forest Service and state agencies. In this case, payments will come from the Yuba Water Agency, whose reservoirs receive water from the forest and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection.

And the bond couldn’t come at a better time in the investor community, as an increasingly popular trend of socially conscious investing is taking off. It’s called ESG, which stands for environmental, social and corporate governance. It focuses on investing for the greater good; in this case, buying into the health of the forest but still making money.

It is exactly the kind of investment Jennifer Pryce, CEO of Calvert Impact Capital, says her clients want.

“Our investors are looking for an impact and a financial return, and this is off the charts when you look at what it’s giving back,” said Pryce, who polls investors each year to see how they want to align their capital with their values. “Fighting climate change is No. 1.”

She admits this one was a difficult sell because it is designed to prevent fires, rather than fight them. Still, once the possibilities and savings were made clear, the investors were in.

It’s not exactly “fighting climate change” either. I wonder what else might get lost in translation, and would the “environmental” investors necessarily like the “other rehabilitation” that the Forest Service decides to fund with their money, and whether there are any restrictions on what an agency could use the funds for. An interesting concept though …

Larry Parnass wrote this story about a July windstorm in Wisconsin- worth reading in its entirety- also excellent photos. For westerners, it’s interesting that even though they have a healthy forest products industry, they too suffer from needing to remove the kind of woody material for which there is no market, or the prices are so low that removal can’t pay for itself. Too bad they can’t do chip and ship, as we previously discussed for Northern Arizona. Also the need to clear roads and keep people safe from falling trees seems like some of our insect-induced disturbances. We don’t hear much about the forests in the upper Midwest and I, for one, would like to hear more.

Their devastation remains topic No. 1 across Oconto and Langlade counties. As repairs and cleanups continue three months later, officials who manage federal, state and county forests still labor to grasp the extent of damage. The U.S. Forest Service estimates that at least 63,000 acres of the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest were affected — a land area larger than the city of Milwaukee.

That impact doesn’t include blowdowns in state and county forests in the area, all of which have sent timber and pulpwood prices tumbling due to oversupply, taxing the ability of forest managers to get salvage wood to market before it spoils.

In early August, the state Department of Natural Resources, using initial field and aerial surveys, pegged the damage at more than 250,000 acres — that’s 390 square miles — including 14,577 acres of state land and 53,647 acres of private land open for public recreation.

Barron and Polk counties in northwest Wisconsin were also badly hit, with spotty storm damage in Wood, Portage and Waupaca counties west of Green Bay.

Richard Lietz, Oconto Falls team leader for the state DNR’s Division of Forestry, has walked battered woodlands with private landowners, offering advice. “It’s a lot to take in. It comes as quite a shock,” he said. “There are hundreds and hundreds of people that are affected.”

John Lampereur, a U.S. Forest Service staff member in the Lakewood/Laona Ranger District, calls the storm a once-in-a-career event. After seeing tangled mounds of jack-strawed trees, some in piles 15-feet deep, Lampereur made a prediction.

“I told my wife. ‘This is going to change everything. We’re going to be working on this for 10 years,’” he said.

Lampereur, the Lakewood district’s expert on forest management, estimates that at least 10,000 acres of forest saw complete blowdown.

“The scale of it is so big that you feel powerless to effect what you consider meaningful change,” he said. “We’re going to do our best. To say that we are going to clean up 50,000 acres, it’s not happening.”

Simply put, there is too much wood for the region’s forest-products industry to handle, even in a state that ranks in the top 10 in this sector.

“We’re only going to be able to absorb so much,” Lampereur said of forest products going onto the market as a result of the storm. “We’re kind of a can-do bunch. It’s hard to swallow your pride and say we’re not going to be able to do it all.”

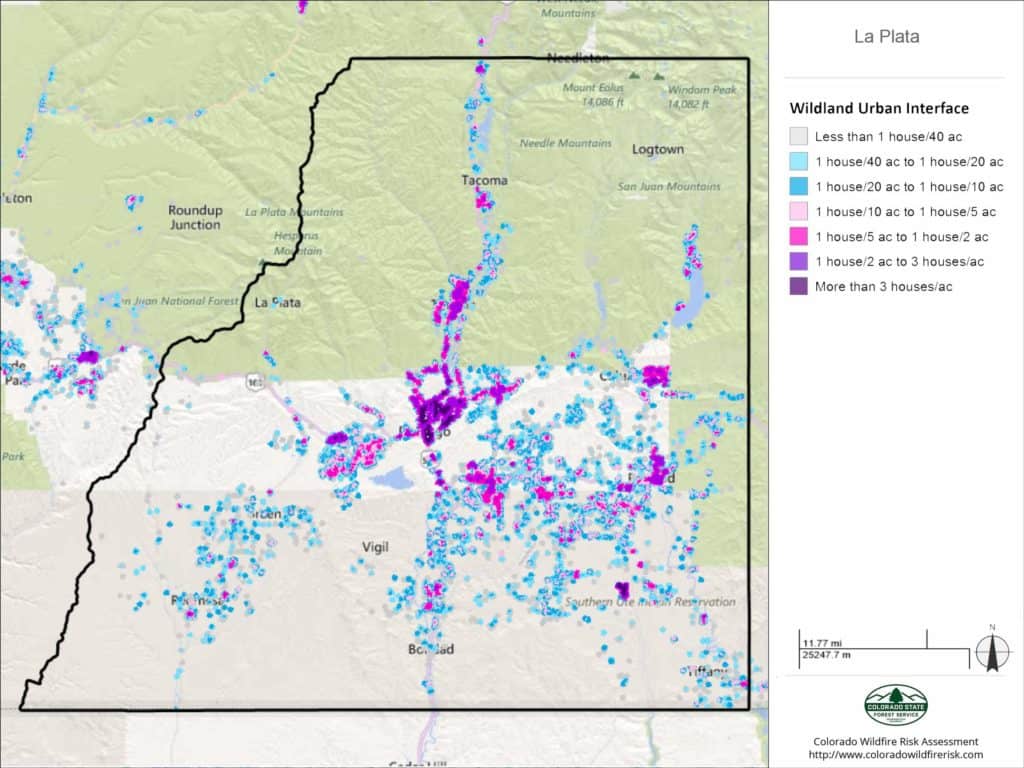

Durango Herald file

Southwest Colorado could be the focal point of a pilot project that seeks to make strides in improving forest health in the face of increasing dangers from wildfire, disease and beetle kill.

Earlier this year, the National Wild Turkey Federation approached the U.S. Forest Service to talk about the challenges in forest management that impede fast-paced and large-scale landscape restoration.

In the past, the Forest Service has tried to spread its budget for forest health projects evenly across a landscape, said Kara Chadwick, supervisor for the San Juan National Forest.

“We’ve been struggling with this as an agency for a while,” Chadwick said. “We get a little bit done everywhere.”

But forest officials started to wonder: What if you directed all your resources, in terms of time and money, to one or two places to accomplish critical improvements, rather than make slow progress in multiple places.

“The idea is to focus in one place, and once you’ve achieved that change on the landscape, move to another,” Chadwick said.

The project is called the Rocky Mountain Restoration Initiative, or RMRI.

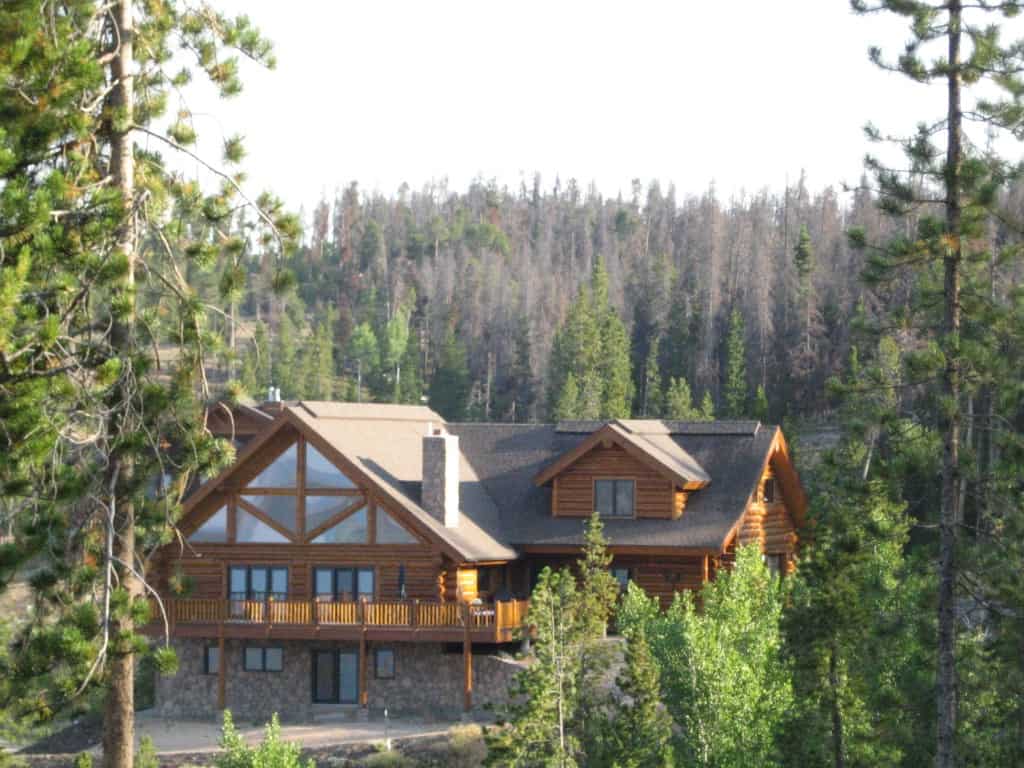

Colorado was chosen as the state to pilot the project for several reasons: It’s home to the headwaters of four major river systems; nearly 3 million people live in the wildland-urban interface; and outdoor recreation is a big part of the state’s economy, to name a few.

Within the state, three regions are being considered to test the project: the central Front Range, the Interstate 70 corridor and Southwest Colorado.

…

The idea, Chadwick said, is to work across all boundaries – federal, state and private lands – to make “transformative change” on the landscape through projects like forest thinning, prescribed burns and boosting logging operations.

Chadwick said areas around Durango, west along the U.S. Highway 160 corridor and up to Dolores could be areas of particular focus.

In La Plata County, for instance, about 53,800 people, or 96.9% of the total population, live in the wildland-urban interface.

Another major part of the program is to improve and protect watersheds. Mike Preston with the Dolores Water Conservancy District said the pilot project could also be used to thin badly overgrown ponderosa forests in the Dolores River watershed.

Past forest management practices have created too-dense tree stands, which can exacerbate issues with wildfire and beetle spread, as well as suck up an inordinate amount of water, Preston said. Encouraging prescribed burns and forest thinning through harvest sales could help with all these issues, he said.

“The problem is, with limited resources available to advance forest health, the pattern has been to spread resources across the entire forest,” he said. “With this project, we’re attempting to concentrate on one or two projects and see what can be accomplished moving more aggressively and timely.”

Chadwick said the hope is to have a final decision on the pilot project by this December. Any work on the landscape would have to go through the National Environmental Policy Act, which requires a study on the environmental impacts of a particular project.

“I think we can get a lot of really good work done, and in the process, build better relationships across the landscape,” she said.

The story is about Sagehen Creek Field Station run by UC. Well worth reading in its entirety. Lots of leadership, including by Scott Conway the silviculturist as well as I’m sure many others on the District, the Sagehen Creek folks, collaboration and patience. Sure, we all talk about the need for prescribed burning, but in this New Yorker story, the fact that it is University of California researchers saying it (and mechanical treatments prior) gives it extra cred in some communities.

As he led us through the trees, Brown pointed out that we were following an old railroad bed. Sagehen was clear-cut in the mid-nineteenth century to help build the railways and mines of the gold-rush era. (Sutter’s Mill, where the first gold was discovered, in 1848, is less than a hundred miles away.) After loggers felled the large trees, smaller ones became fuel for locomotives, and the eastern slopes of the Sierra are so dry that there are still stacks of cordwood left over from the eighteen-eighties. Nearby, Brown bopped up and down on pine needles that coated the ground. “See this?” he said. “These go down ten inches deep in places.”

In 2004, one of Brown’s colleagues at Berkeley, a fire scientist named Scott Stephens, came to Sagehen and took samples from the stumps of huge trees cut down during the gold-rush era. Examining tree rings and scorch marks, Stephens was able to construct a record of fires dating back to the sixteen-hundreds. His findings confirmed that, in pre-Colonial times, Sagehen burned regularly. Those fires sometimes occurred naturally, from lightning strikes, but they were also deliberately set by Native Americans. The consensus now is that the entire Sierra Nevada burned every five to thirty years.

So they tried to design some SPLATS (previously discussed here in an TSW interview with Dr. Mark Finney.

Brown and the rest of the Sagehen planning team decided to pursue a strategy that had recently been developed by a Forest Service scientist at its Rocky Mountain Research Station. Affectionately known as splat, for Strategically Placed Landscape Area Treatment, the technique involves clearing rectangular chunks of forest in a herringbone pattern.This compels any wildfire to follow a zigzag path in search of fuel, travelling against the wind at least half the time. The splats function as speed bumps, slowing the fire enough that it can be contained, while allowing the Forest Service to get away with treating only twenty to thirty per cent of any given landscape.

Adapting the splats to Sagehen’s terrain took four years. Then, just as the plan was being finalized, a paper was published documenting the unexpected decline of the American pine marten at Sagehen. The marten, a member of the weasel family, is not endangered, but its population levels are seen as a useful proxy for forest health. Soon, the Sagehen planning team heard from Craig Thomas, the director of the environmental group Sierra Forest Legacy, which has a long history of litigation against the Forest Service. Thomas asked them to redesign the project, with an eye to protecting marten habitat.

Thomas, a small-scale organic farmer in his seventies, told me that he was astonished when the Sagehen group, especially the Forest Service, seemed open to the idea. “Instead of getting their backs up, they jumped in with both feet,” he said. Conway recalled his own response a little differently. “I was, like, really?” he said. “It meant a bunch of complexity, and making this project, which was already really too long, much, much longer.” Still, as Thomas recalls, Conway “went away and read every marten ecology paper in existence by the time the next phone call happened. And I went, Ah, this is somebody I think I want to work with.”

So in 2010 the team, which had now been working together for six years, began planning all over again, this time with an even larger group of collaborators and a more expansive goal. “It started as science, but it became diplomacy,” Brown told me. “How could we get all these people—groups that didn’t trust each other, were actively suing each other—to a consensus on what was best for the forest?”

Brown secured grants, hired a professional facilitator, and brought together loggers, environmental nonprofits, watershed activists, outdoor-recreation outfits, lumber-mill owners. Sometimes there were upward of sixty people at meetings. Scientists from all over the region presented the latest findings on beaver ecology or the nesting behaviors of various bird species. To categorize Sagehen’s diverse terrains—drainage bottoms with meadows and those without, north- and south-facing slopes, aspen stands with conifer encroachment—working groups hiked almost every yard of the forest.

Arriving at a consensus took years of discussion, but, in the end, the strategy the team decided on turned out to mimic the way fire naturally spreads. For instance, fire burns intensely along ridges and more slowly on north-facing slopes. Martens, having adapted to these conditions, rely on the open crests to travel in search of food and mates, while building their dens in shadier, cooler thickets. Following the logic of fire would create the kind of landscape preferred by native species such as the California spotted owl or the Pacific fisher—a mosaic of dark, dense snags and sunlit clearings, of big stand-alone trees and open ridgelines connecting drainages. Conway then led an effort to formulate a detailed implementation plan whose treatments varied, acre by acre, according to the group’s predictions. Some areas were to be left as they were, some were to be hand-thinned with a focus on retaining rotting tree trunks, and some were to be aggressively masticated and then burned.

Typically, a Forest Service project takes two months to plan. Sagehen had been in the works for nearly a decade, but Brown eventually achieved the impossible: a plan that everyone—environmentalists, scientists, loggers, and the Forest Service—agreed on. Then, three days before the group was due to sign off on the plan, there was yet another hitch: in one of the units of Sagehen that were scheduled to be burned, a Forest Service employee discovered a nesting pair of goshawks—raptors that are federally protected as a sensitive, at-risk species.

This time, it was the conservationists who compromised. “I could have said, ‘O.K., this area is now off limits, and if you don’t believe me I’ll sue your ass,’ ” Craig Thomas recalled. But, after some discussion, he agreed to stick with the plan. He knew that burning might make the birds leave or fail to fledge young, but, he told me, “the collaboration effort and what we had accomplished together mattered more.”

But, despite the success of the project, enormous challenges remain. The Forest Service struggles to muster the resources and the staff necessary to burn safely. The California Air Resources Board restricts prescribed burns to days when pollution is at acceptable levels and the weather likely to disperse emissions from fire. In practice, this means that burning can occur only during a few weeks in the spring. In summer and autumn—the seasons when forests would burn naturally—the state’s air usually falls foul of the Clean Air Act. These are also the months that are most prone to uncontrollable wildfires, whose smoke is far more damaging to human health than that from prescribed fire. But, perversely, because wildfires are classified as natural catastrophes, their emissions are not counted against legal quotas.

Across the region, the Forest Service is devising projects to thin and burn on the Sagehen model. Meanwhile, Brown has helped launch the largest forest-restoration venture yet undertaken in California: the Tahoe-Central Sierra Initiative. It encompasses an enormous swath of forest that extends as far north as Poker Flat, level with Chico, and as far south as the American River, level with Sacramento. Brown’s goal is to return fire to three-quarters of a million acres in the next fifteen years.

This may sound like the same old..but again, why not export chips? I’d expect to see something more organized in California or with other states to develop markets for this material, e.g.chips to South Korea in Arizona, CLT mill in Washington, and so on. At least there would be folks at Cal working on this. When did using stuff become less-cool research? Back in the day. it would have been a good research consortium proposal with related education and extension to apply for NIFA grants. We have been talking about this for at least 20 years..

Brown has begun working with a group of researchers at U.C. Santa Cruz to imagine the outlines of a timber industry built around small trees, rather than the big trees that lumber companies love but the forest can’t spare. In Europe, small-diameter wood is commonly compressed into an engineered product called cross-laminated timber, which is strong enough to be used in multistory structures. Another option may be to burn the wood in a co-generation plant, which produces both electricity and biochar, a charcoal-like substance used to replenish soil. Brown has also been talking to a businessman who hopes to burn waste wood to heat an indoor greenhouse-aquaculture operation. His vision is to provide organic vegetables and shrimp to buffets in Las Vegas, and then to interest California’s cannabis farmers in using shellfish-dung-enriched biochar as fertilizer.

Here’s also a link to George Wuerther’s comments published elsewhere. https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/09/02/what-the-new-yorker-got-wrong-about-forests-and-wildfires/

There are sidebars that scientists working at Forest Service Research Stations or professors in forestry schools must observe if they want to keep their jobs and/or funding. These individuals do not fudge the data, but they start with specific questions and assumptions that beget certain conclusions.

Really? And others don’t frame questions that beget “certain conclusions”?

Lourenço Marques posted this as a comment:

He had seen this on FB.

Today the Montana Bicycle Guild, Inc., filed a motion to intervene in the lawsuit in the U.S. District Court brought by Helena Hunters & Anglers and Montana Wildlife Federation against the U.S. Forest Service. The MBG is intervening to support the Forest Service’s decision on the Ten Mile-South Helena Project and to protect the interests of mountain bikers.

“As part of the post-disturbance restoration for this project, the Forest Service adopted several long-established trails into the trail system inventory and also approved the construction of three new thoroughly vetted and needed trails.

“The lawsuit brought by Helena Hunters & Anglers and Montana Wildlife Federation challenges the incorporation of existing trails into the inventoried system. Their lawsuit also seeks to prevent two of the new trails in this area from being built. . . .

“This would end-run years of work and collaboration to impose a de facto ban of bicycles from every trail in this area targeted by their lawsuit. If the Helena Hunters & Anglers and Montana Wildlife Federation lawsuit is successful, the bicycling community would suffer a major loss and be banned from this entire area.

“This project doesn’t only impact bikers—every public land user would lose a couple of well-thought-out new trails that is the result of numerous people and groups working together for many years, including the MBG, to plan and collaborate with the Forest Service.”

Lourenço asks “Would any employees of or participants in the public-lands litigation factory care to explain how this lawsuit benefits the cause of conservation?”

It seems pretty much BAU to litigate fuel treatment projects in Montana. The interesting twist is about the trails. From this Independence Record story:

The project calls for logging, thinning and prescribed burning on 17,500 acres near Helena. Goals primarily focus on wildfire concerns, with the aim of creating safe places to insert firefighters and reducing a wildfire’s potential severity. A smaller aspect of the project includes trail designations and construction, which has drawn some criticism — and now lawsuits — over concerns of drawing mountain bikes into roadless areas.

The association and federation’s lawsuit was recently consolidated with a separate and much broader lawsuit filed by Alliance for the Wild Rockies and Native Ecosystems Council. While the first lawsuit only challenges work in inventoried roadless areas, the second lawsuit challenges the entirety of the project and calls for it to be halted due to allegations of inadequate environmental analysis and impacts to wildlife.

The guild is challenging the trail portion of the lawsuit. The group contends that multiple trails in the project area have been used for decades by mountain bikers and notes that the project decision prohibits mountain bikes from leaving designated trails. The project officially designates two trails that have seen traditional bike use as well as construction of two multi-use trails in the Jericho and Lazyman Gulch inventoried roadless areas, the guild says.

Is this about kicking bikers off trails they currently use? But bike use is legal in roadless areas.. It’s all very confusing.

I also noted that the State is an intervenor as in this story from KTVH.

Finally, to make the whole project even more confusing, the project is currently underway while the lawsuits move forward according to this article that talks about the implementation (with good photos).

“Courts have not ruled on or temporarily halted the project as it hears the cases, however the Forest Service has agreed to suspend work in roadless areas until the court has ruled on the first lawsuit.”

Here’s an op-ed on the Collaborative and how their opinions were used in the decision.

Here’s a link to the EIS and Matthew Garrity’s (AWR) objection letter

Some of his claims are interesting:

The purpose of the project according to the DROD is to: “Reduce the probability of high-severity wildfires and their associated detrimental watershed effects in the Tenmile Municipal Watershed and surrounding area.”

This is a violation of NEPA since the project will not do this and the purpose also violates NFMA and the APA since trying to fireproof a forest destroys a forest and makes an unhealthy watershed.