One is an Associated Press overview of the firefighting cost issue. It’s not research, but it is the way the problem is viewed by many people. Here is why they say costs are going up:

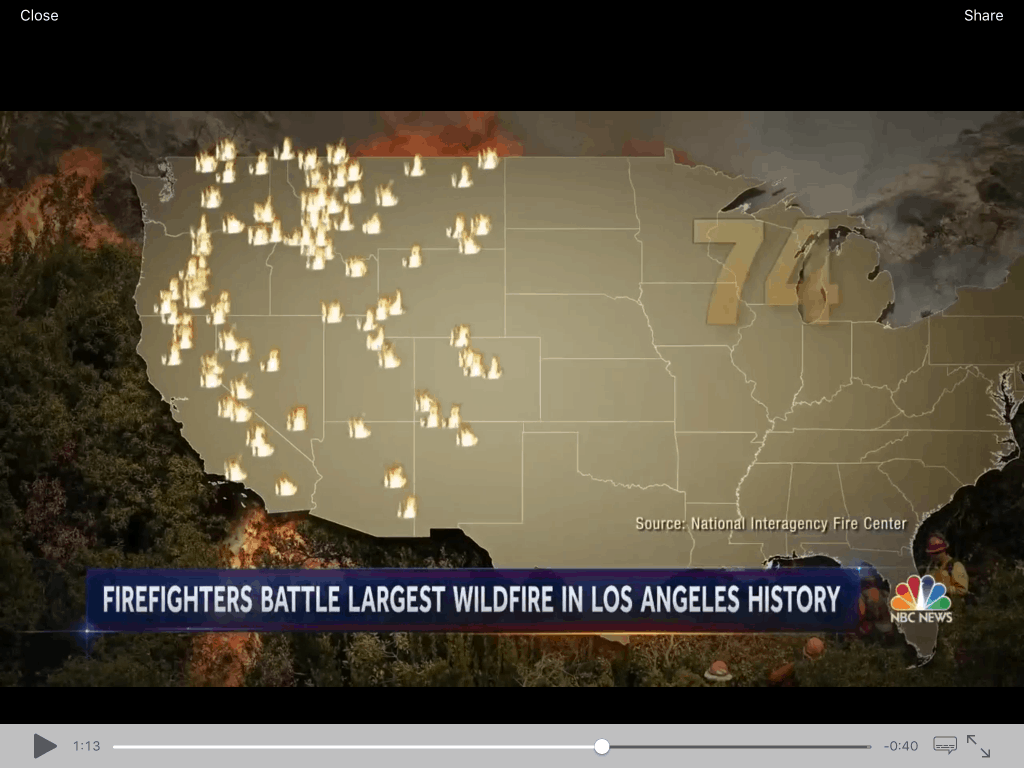

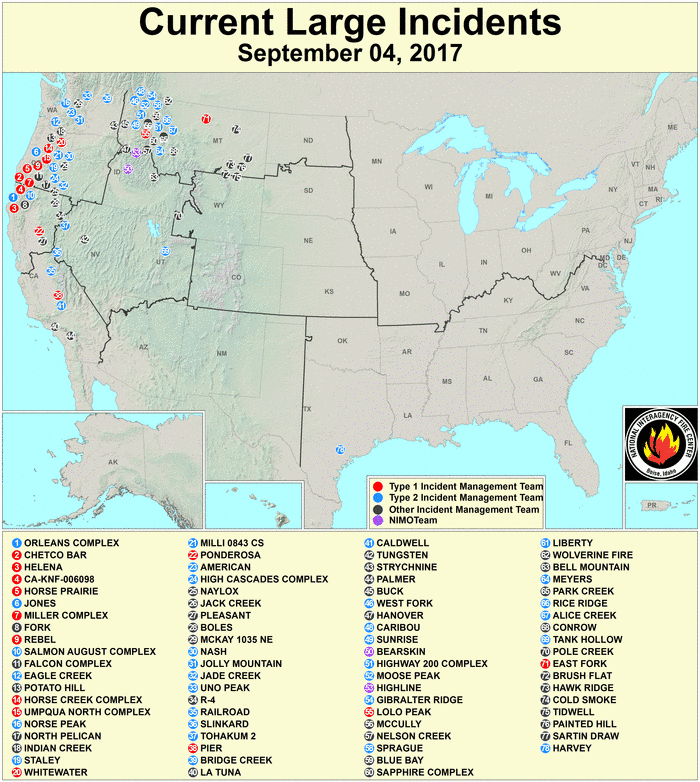

The U.S. is seeing more and bigger wildfires, and the wildfire season is getting longer. The reasons are hotter, drier weather and a buildup of dead and dying trees because of past fire-suppression practices, said Jennifer Jones, a spokeswoman for the National Interagency Fire Center, which coordinates firefighting nationwide.

The old practice of putting out all fires led to overgrown forests, some with huge tracts of trees that died at about the same time, leaving them prone to large, hot, fast-moving blazes, researchers say.

Some climate and forestry experts say global warming is a factor in the increasing number of fires because it’s contributing to the hot, dry weather.

Jones said another development driving up costs is the increasing number of homes being built in or near forests, a number that the Forest Service estimates is about 43 million homes. Keeping fires away from people, houses, power lines and other infrastructure is more complicated and costly than firefighting in the wilds.

I noticed the absence of “not enough thinning” or “serial litigants.” Although there’s allusions to both in the last paragraph on legislative solutions (even though they’re not described as a cause):

But one also calls on the Forest Service to manage its woodlands more actively, including thinning dense stands of trees and removing dead trees in an effort to reduce fires. Some argue that pushing management practices is unnecessary and ineffective.

The other features Stephen Pyne discussing what “let it burn” means today in Arizona. The title: “Nature is clearing more forest than people can. That may be a good thing.”

It’s complicated, but the gist is this: When lightning-caused fires do not threaten homes, let them burn. That’s an overgeneralization for an approach that takes many factors into consideration such as burn scares from previous fires, weather, drought, fuel, resources, firefighter safety and nearby communities.

Firefighters are frequently “going to managed wildfire, or a box and burn strategy,” Pyne said. Roads, trails and other barriers serve as fire lines. Those lines are the box. The burn clears brush within them. Each box cleared is less likely to be part of a giant fire in the future.

“You’re not just walking away and letting it go,” Pyne said. The strategy is not new — it has quietly been going on for years, said Zabinski. “It’s happening quietly all around, but more so the last few years,” she said, because the recent years have brought some drought relief.

The strategy is not without risks because “nature’s complicated. People make mistakes. Things happen,” Pyne said. But without it, “we’ll be playing Whac-A-Mole into the indefinite future. And we’re not going to win.”