The Great Falls Tribune and Helena Independent Record recently teamed up (whether they knew it or not) to present a fairly cool multi-media education about the Forest Service’s “let it burn” policy as it applies to the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex and this summer’s Red Shale wildfire.

Not surprisingly, the Forest Service is finding that following nearly 30 years of following such a policy in the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex, fuels have been reduced, wildlife habitat has been created and US taxpayers have enjoyed significant wildfire suppression cost savings (again, whether they know it or not).

First, I highly recommend watching this short video from the Great Falls Tribune. Mike Munoz, Rocky Mountain District Forest Ranger on the Lewis and Clark National Forest is interviewed and gives some of the recent wildfire history in the Bob Marshall, as well as some of the rationale and justifications for the Forest Service’s “let it burn” policy. The video includes some pretty cool GoPro footage from high about the Bob Marshall, so enjoy some of those images.

Next, Eve Byron of the Helena Independent Record has a more extensive story, parts of which are highlighted below.

Twenty-five years ago this month, the Canyon Creek fire roared out of the Scapegoat Wilderness after slowly burning unfettered for more than three months, deep within the mountains, under part of the so-called “let it burn” U.S. Forest Service policy.

Eventually, the Canyon Creek fire burned across more than one-quarter of a million acres, forced the deployment of shelters by more than 100 firefighters and threatened the town of Augusta.

The local firestorm of criticism over the Forest Service’s handling of the Canyon Creek fire lasted even longer than the conflagration. But valuable lessons were learned, and this summer, as the Red Shale fire was allowed to burn relatively unchecked through the wilderness, it did so with little fanfare.

Brad McBratney, the fire staff officer for the Helena and Lewis and Clark national forests, and Rocky Mountain District Ranger Mike Munoz smile at questions about various firefighting tactics used by the Forest Service, well aware that the public typically has a limited understanding of how decisions are made as to whether to try to extinguish wildfires in wilderness areas or let them burn. They pull out two yellowed documents from the early 1980s, which foresters have used in the ensuing decades to put policies into practice on the ground, and half a dozen maps showing how fires have shaped the 1.5 million-acre Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex landscape since then.

“In 32 years, we have seen some significant fire activity on the landscape,” Munoz said….

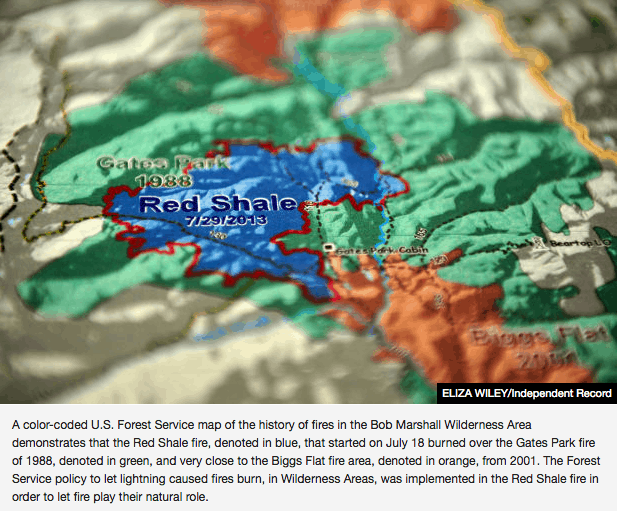

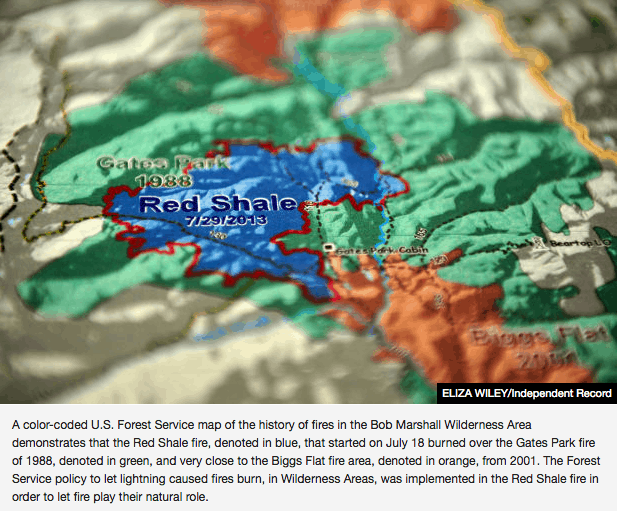

McBratney and Munoz point toward this summer’s Red Shale fire as a textbook example of fire management, even though it is still burning after being started by lightning on July 18, about 35 miles west of Choteau. The fire has spread over 12,380 acres in a typical mosaic pattern, burning trees in one area but leaving others standing. Most of the burned area is within the footprint of the Gates Park fire, which ended up totaling about 52,000 acres.

They do more up-front planning, which includes examining various long-term scenarios. They get daily briefings on weather. More resources are in place — both people and equipment — if it’s needed. They map using satellites and infra-red radars. The develop models on where the fire is expected to burn and revisit those models regularly to tweak them.

Public information officers posted daily updates on a fire’s size, location and the number of resources assigned to it in Choteau and Augusta. There’s even an “app” that allows cell phones to scan it and go directly to the online “InciWeb,” a national incident management website that posts fire information, to learn more about the Red Shale fire.

Even if they’re not actively trying to extinguish the flames, they still use helicopters to drop water to cool the blaze and try to direct it away from some areas. They’ve wrapped historic cabins with fire-resistant materials and installed sprinklers as protective measures.

At the height of the Red Shale fire, about 25 people were assigned to it, including about 10 people on the ground. Today, four people are watching the fire, which is mainly smoldering after recent rains and cooler fall temperatures.

Today, after 100-plus fires in the Bob Marshall Complex have burned hundreds of thousands of acres since 1980, there’s less fuel to add to the fires. Munoz points to the Red Shale fire map, which shows how it burned to the edge of the 2001 Biggs Flat fire, then stopped without human intervention.

In addition to the natural fires within the wilderness area, forest officials have used prescribed burns to remove fuels outside the boundaries, with the hope that will make it easier to catch a fire that makes a run toward private property.

They’ve also worked on building relationships with local and state firefighters. McBratney is a member of the Augusta volunteer fire department, and Stiger said that during the recent fire season local volunteers meet weekly with state and federal representatives to talk about potential issues.